Introduction

Quality improvement research is the combined and continuous efforts of everyone—healthcare professionals, patients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators—to make changes that lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care), and better professional development.1 Healthcare professionals have documented quality improvement efforts extensively within the literature.1–5 An impactful example of quality improvement research is recounted in Atul Gwande’s book The Checklist Manifesto, where he describes the implementation of a safety surgical checklist within operating rooms that resulted in a substantial decrease in surgical complication rates.6 Quality improvement research has assisted solution-driven efforts within an extensive list of healthcare settings and specialties, all of which began with one consistency; a problem that needs solving.

Compared to other health professional training programs, hospital-based pre-licensure training opportunities are relatively uncommon in the chiropractic profession. Two-thirds of doctor of chiropractic programs hold academic affiliations with Veterans Health Administration (VA) facilities, which allow students of those programs to gain integrated clinical experience within hospital environment.7,8 Also known as “clerkships”, these student training opportunities are generally made available to students in the final year of their clinical training, where they are supervised by chiropractic attendings. Typically, student candidates apply to the clerkship programs and are selected through a competitive interview process. The duration of the training varies by institution, often ranging from 3-9 months, with a primary focus on developing students’ clinical skill sets in an attempt to better prepare them for chiropractic practice. A unique feature of these training programs include increased exposure to complex, multi-morbid patient encounters which are less common in an outpatient or student clinic setting.9 Due to the level of case complexity, extensive chart volume, and lack of familiarity with the hospital system’s electronic health record (EHR) software, our trainees have found that the chart review process can be time-consuming and overwhelming. Checklists are commonly used in various healthcare settings as a tool to improve clinical efficiency and to mitigate unnecessary safety risks during medical procedures.10–17

We developed a novel chart-review checklist tool to support chiropractic trainees in identifying clinically relevant information, with the goal of instilling trainee confidence for clinical decision-making. The purpose of this report is to describe the chart-review checklist tool we developed and piloted with a single chiropractic student trainee.

Methods

We developed the chart review checklist tool to support VA chiropractic trainees with performing comprehensive chart reviews before the initial patient encounter. The chart reviews are completed on the same day as the patient encounter. This checklist tool was designed through an iterative process with feedback from several staff chiropractors and several rounds of revisions. We did not have a specific model for our checklist, and instead designed the checklist tool based on the VA EHR in a “do-confirm” format. A “do-confirm” checklist format is designed to be used as a final procedural review, confirming a process or task was performed without missing pertinent details. There were 4 distinct categories of focus: 1) consult, 2) relevant note review, 3) imaging/labs/surgical reports, and 4) cover sheet. (Figure 1) The title of each category signifies specific tabs within the EHR. Each of these categories contained a subset of two to four checklist items. Checklist review tools should be able to be completed quickly in their entirety.

In addition to the checklist tool, the student was provided training and instructions on how to complete the chart review checklist tool. (Figure 2) This summary reviewed the “do-confirm” checklist format, objectives for implementation, and communication strategies between supervisor and trainee to gauge the effectiveness of information collection and retention.

Upon checklist completion by the student, a review of the case was performed with the supervising chiropractor. The trainee presented the case information to their assigned attending supervisor using an SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) communication approach. The SBAR is a standardized communication strategy for communications case information within a healthcare setting.18 The supervising chiropractor determined if the trainee chart review was adequate and utilized these conversations as teaching opportunities.

Checklist Categories

Consults

The “consults” tab (Figure 3) in the EHR is a record of all patient consultation request from providers to specialty clinics for an individual patient’s care within the local VA healthcare facility. The “consult” category of the checklist included two items confirming the trainee reviewed the, 1) incoming consult submission by the referring provider to the chiropractic clinic, as well as, 2) any other referrals that have been initiated to specialty clinics (e.g., neurology, neurosurgery, orthopedics, comprehensive pain management, etc.) for musculoskeletal concerns during the prior 12 months.

Notes

All chart notes completed at the local VA facility are found in the “notes” tab (Figure 4) of the EHR. The “relevant note review” category included three checklist items; 1) a review of the note from the referring provider associated with the date of chiropractic consultation request submission, 2) a review of the most recent primary care provider note if the referring provider was a specialist, and 3) any emergency department notes from the prior 6 months.

Imaging/Labs/Surgical Reports

All imaging reports, lab results, and surgical reports can be located in the EHR “Reports” tab (Figure 5). We identified these as important components of the clinical decision making for the chiropractic clinic. As related to the patient’s primary or secondary region of complaint, we asked the trainees to confirm review of; 1) radiologist reports, 2) laboratory results, 3) electrodiagnostic reports, and 4) surgical reports.

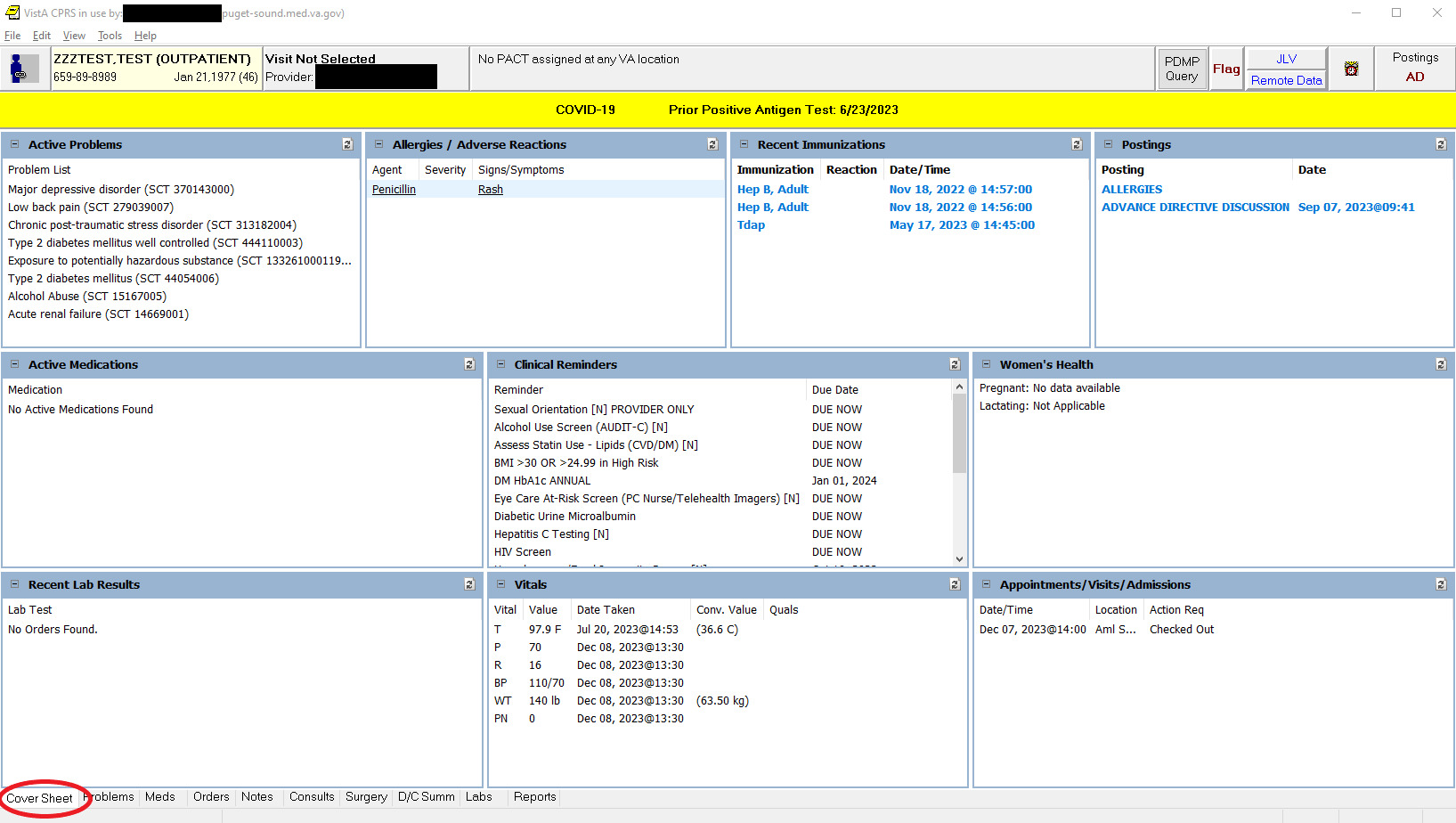

Cover Sheet

The fourth and final tab and category of the checklist tool included is the “cover sheet” (Figure 6). The “cover sheet” offers the provider a single-screen summary of several important patient health factors. For our purposes, the “cover sheet” section of the checklist included review of; 1) active problem list, 2) active medication list, 3) most recent vital signs, and 4) upcoming patient appointments.

Results

The chart review checklist was used by the trainee for a 12-week duration, encompassing a total of 27 new patient encounters. Informal feedback was sought from the student trainee following the completion of the checklist tool pilot duration. All 27 of the cases where the checklist tool was used were deemed to have had adequate chart reviews following discussion via the SBAR communication with the supervising chiropractor.

VA chiropractic student impression of the chart review checklist tool

Informal feedback was solicited from the student trainee regarding the checklists impact on his chart review experience. When asked about how the student’s ability to perform a chart review has changed following this checklist tool implementation, the trainee stated “The utilization of the chart review checklist tool allowed me to efficiently navigate the information available in the EHR, making the process more conducive to a new and foreign learning environment. Having minimal training with reviewing extensive patient charts prior to this integrative opportunity, I found this process helped minimize the learning curve to catch me up to speed.”

When asked about whether this chart review tool provided valuable learning opportunities, the student responded “If I found that knowledge gaps existed within reviewed patient chart information, the checklist allowed me to formulate questions to ask my supervisor which resulted greater teaching moments. This was something I found helped to further develop my knowledge and clinical reasoning skills when approaching a more complex patient demographic.”

When asked whether this tool impacted their confidence levels entering new patient encounters, the trainee responded “chiropractic care in the hospital setting allows for ease of access to information, but with a plethora of information available it can be daunting to navigate, let alone know where to start. The checklist streamlines this process and creates a standard for reviewing and preparing prior to a new patient encounter. This gave me an outline to ensure the chart was reviewed thoroughly and appropriately so I was prepared to expand upon the patient’s condition when seeing them in the initial encounter.”

When asked if this tool should be used for future trainees, they responded “I believe that future VA trainees who are new to the hospital setting will greatly benefit from this learning tool. I’ve recognized in my own experience it has the potential to sharpen your clinical skill set, approach to patient management, and ability to curate more thoughtful discussions surrounding case information with attendings and other colleagues”.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first publication to describe chart-review processes or checklist implementation within chiropractic clinics or with chiropractic trainees. Implementation of checklists has been shown to be a useful tool to promote positive change in a variety of health care settings (i.e., anesthesiology, internal medicine, pathology, radiology, cardiology, critical care, obstetrics, and fall prevention clinics).10,11,13–15,17,19–21 Some of the more notable findings from these studies demonstrated that checklist improve information transfer following surgical procedures, documentation of critically important case elements, recognition of previously missed prevention interventions, work load efficiency and decreased surgical complication rates.10,19,21,22 This reiterates the potential benefit these tools can promote and their flexibility of application.

Haugen et al. reported that the effectiveness of checklist tools is limited by consistency of operator adherence to the tool, as well as potential burden of time and effort.16 Very few studies reported any negative patient outcome effects.16,23 There are relatively few examples in the literature describing checklist implementation in clinical education settings. In one study, Pearson et al. demonstrated that comprehensive chart review checklists embedded within medical wards improved confidence of medical trainees when rotating through ward rounds.24

After piloting the checklist tool with a single trainee for 12 weeks, we feel that there was sufficient benefit to warrant further implementation with all the chiropractic trainees at our facility. Our student in this pilot project reported high satisfaction with the instrument regarding their level of confidence upon entering a new patient encounter, efficiency in completing the chart review, and impact on case communication skills. The student recommended the checklist tool be used by future trainees without additional revisions.

We feel the lack of available literature on this topic offers an opportunity to further expanded upon this quality improvement project by involving more trainees at multiple VA sites, or modifying accordingly to use in other settings with integrated EHR systems. The next steps for a future study could include evaluating feasibility of expanded clinical implementation of the chart review checklist tool, formally surveying chiropractic trainee experience, or collecting data on the information reviewed in the chart-review process.

Limitations

This descriptive report has several limitations. First, the checklist was piloted by a single trainee who was primarily supervised by a single chiropractor and the perceived benefit may not be generalizable to other trainees or clinicians. Since we piloted the checklist with a single student, we could not determine if checklist implementation added benefit to the naturally occurring learning process. Second, the checklist tool was used for relatively few patients over the 12-week duration, and it is unknown how the trainee’s opinion and efficiency using the tool changed over time. It is possible that sustained implementation of the checklist could be viewed as a burden by trainees after they acclimate and are fully trained in the chart-review the process. Use of surveys over multiple time points in training could provide additional insight. Third, the checklist tool is not validated, and it was developed specifically for compatibility with the VA EHR and may not be generalizable to non-VA settings or when using other EHR systems.

Conclusion

Utilization of a comprehensive chart review checklist tool may benefit trainee chart review skills and confidence in adapting to new EHR systems. Further study is needed to assess checklist feasibility, validity and efficacy of a chart review checklist tool in chiropractic settings.

Authors’ Note

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. This project received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency. The authors received indirect support from their institutions in the form of computers, workspace, and time to prepare the article.