Introduction

Syringomyelia is a condition in which a fluid-filled cyst develops within the spinal cord due to a disturbance of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow. It may be congenital and associated with Chiari malformations or it may be acquired as a rare sequela of spinal cord injury, meningitis, arachnoiditis, tumor or tethered cord. The size of the syrinx may increase over time, resulting in compression and worsening symptoms, which may lead to neurological deficits or require decompressive surgery.1 MRI is the preferred diagnostic imaging modality, offering high sensitivity without requiring IV contrast.2,3

Non-surgical spinal decompression is a computer-driven motorized traction of the spine, with the goal of relieving pressure on spinal structures, such as discs, facets, cord, and nerve roots. Indications include disc bulge or herniation, disc degeneration, facet syndrome, sciatica, and back or neck pain. There is support for traction as a non-surgical treatment option for cervical radiculopathy.4,5 The addition of computer technology to traction in non-surgical spinal decompression is intended to overcome muscle guarding and lower intradiscal pressure into the negative range, and has been shown to restore lost disc height and reduce the size of disc displacement.6–8 This treatment is frequently used in combination with other physiotherapy procedures and has been included in the curriculum or as a postgraduate course at several chiropractic colleges.9

Case Report

A 48-year-old female presented with chronic neck pain that onset 11 months prior after being the restrained driver in a rear-impact motor vehicle collision. She described constant neck pain, with a sore, throbbing, achy quality, pain radiating to both shoulders, frequent headaches, and bilateral upper extremity paresthesia that was most intense in her right hand. She rated her pain as a 7/10 on a numerical pain scale and completed a Neck Disability Index (NDI) with a score of 38%. She also reported low back pain. Neck pain interfered with exercise and she reported having gained approximately 30 pounds since the injury. She experienced bilateral plantar fasciitis, which she attributed to weight gain.

Prior treatment included medications (pregabalin 50 mg bid, celecoxib 200 mg/day, and diclofenac topical as needed), previous chiropractic manipulation, physical therapy, acupuncture and cupping. The initial cervical spine MRI was done 6 months following the crash due to the failure of conservative treatment. The x-ray showed the presence of syringohydromyelia. She was then treated with a series of 3 cervical epidural steroid injections and she had neurosurgical consultation. Decompressive surgery was recommended; however, the patient desired to avoid surgery. Stretching and massage helped alleviate her pain, while sitting, using a computer, and prolonged periods of driving were reported to be aggravating for her complaint. Her occupation in sales required sitting more than 50% of the day. The patient did not recall any past history of neck pain and denied history of surgery, hospitalizations, major illness, or trauma. A review of systems revealed hypothyroidism as a comorbidity. Medications included sertraline, synthroid, and progesterone in addition to those listed above.

Her cervical spine range of motion was restricted in right lateral flexion with pain and audible crepitus. Cervical distraction test was positive by producing relief of her upper extremity symptoms. Weakness was evident at the right upper extremity with finger abduction. Tenderness to palpation, myofascial hypertonicity and joint fixation were present at the cervical spine. Medical records from her anesthesiology and pain management physician were reviewed, including cervical spine MRI.

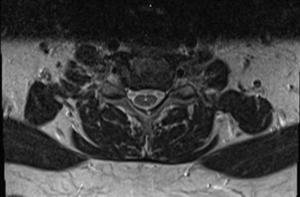

A second MRI examination of the cervical spine without contrast was ordered approximately 1 year following the accident due to persistent and worsening symptoms. This was necessary to evaluate radiculopathy and to rule out enlargement of syringohydromyelia. The syringohydromyelia at the cervical and upper thoracic cord was unchanged compared to a study 6 months prior. Annular tear, mild posterior disc bulging and mild disc degeneration were present at C3-C4. Mild bulging and degeneration was present at the C5-C6 disc with Luschka joint osteophytes and severe foraminal stenosis at C6 on the right. Severe disc degeneration was evident at C6-C7 with mild disc bulging and severe bilateral bony foraminal stenosis at C7. There was no evidence of Chiari malformation, tumor, or other congenital anomalies. (See Figures 1-4)

She was diagnosed with traumatically-induced cervical radiculopathy, cervical spine segmental dysfunction, and syringohydromyelia at the cervical and upper thoracic cord. Pre-existing disc degeneration and osteophytes at the cervical spine may have predisposed her to this condition.

Moist heat therapy, electrical stimulation, and manipulation 2-3 times per week for 1 month (12 visits) brought only a slight symptomatic improvement. Her pain score was 6/10 and NDI 32%. The treatment plan was subsequently changed to include nonsurgical spinal decompression applying 20 pounds at a 100 of cervical flexion for a period of 25 minutes, alternating high and low tension (IDD Therapy® software by North American Medical Corporation). Decompression was followed by cold pack and low-level laser therapy (830nm 90mW) for 10 minutes, seated HVLA manipulation to the cervical spine and myofascial release of the trapezius. She was also instructed on home exercises: 1)neck flexibility, consisting of flexion / extension, rotation, lateral flexion, and scapula retraction, 5 repetitions each once per day, and 2) isometric strengthening exercises, pressing the hands against the head to provide resistance against neck flexion/extension, rotation and lateral flexion, holding the isometric contraction for 5 seconds and doing 5 repetitions in each direction once per day. She received 13 nonsurgical spinal decompression visits over a 2-month time period. Pain was reduced to a final level of 2/10 NPS and 6% NDI. Headaches and upper extremity paresthesia were resolved and she reported mild occasional neck pain aggravated by stress at her job in sales. Her symptoms having considerably improved, she was able to resume exercise with a personal trainer.

Discussion

Existing literature on the treatment of patients with syringomyelia using manipulative and physiological therapeutics is limited. Haas et al. reported on the chiropractic management of a 41-year-old male patient with chronic intractable pain involving a post-traumatic syrinx following a fall, despite occipito-atlantal decompression surgery.10 Chiropractic treatment brought improvement in the cervical lordosis and reduced pain, with benefits maintained at a 1-year follow-up. Demetrious described the chiropractic treatment of a 21-year-old female with post-traumatic upper cervical subluxation, syrinx, and alar ligament disruption, injuries which were undetected initially on x-ray and CT but that were subsequently diagnosed by MRI.11 Chiropractic manipulative treatment combined with rehabilitation exercises brought a resolution of symptoms and the benefits were maintained at a six month follow up. A case report by Tieppo found spinal manipulation to be effective in an 18-year-old female suffering syringomyelia and radiculopathy with associated Type I Arnold-Chiari malformation resulting from motor vehicle trauma.12 The treatment brought about a resolution of symptoms and the author concluded that manipulative treatment by a skilled physician need not be contraindicated.

Conclusion

In this case, nonsurgical spinal decompression brought a substantial improvement in neck pain and disability and excellent long-term outcome despite the case being complicated by syringohydromyelia. At a seven year follow up, she had still avoided spine surgery, using deep tissue massage and chiropractic manipulation occasionally as needed during exacerbation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to acknowledge John Hart, DC, MHSc for mentoring him as an author and reviewer, Larry and Gidgette Rubin for IDD Therapy® technical support, and Kris Fetterman, for her support of nonsurgical spinal decompression continuing education.