Introduction

The biopsychosocial (BPS) model of wellness highlights the significance of biological, psychological, and social factors in shaping an individual’s overall health experience and underscores the importance of considering these factors for effective health management.1,2 The BPS model is considered the standard approach for understanding pain, and current research supports the substantial impact that biological, psychological, and social aspects appear to contribute to the experience of pain chronicity.2

As the BPS model has been studied and refined, complementary treatment regimens based on its findings have subsequently emerged. In recent years, interdisciplinary pain management programs have become the gold standard for treating chronic pain and have encouraged the integration of many professional disciplines towards managing the sensory experience of pain, alongside psychological and social vulnerabilities.3,4 Historically, interdisciplinary teams have primarily consisted of some combination of general practitioners, pain specialists, nurses, physical/occupational therapists, and psychologists.3,4 However, recent advances on the integrative medicine front have highlighted the importance that chiropractic care plays in pain outcomes,5–8 thus expanding these inter-professional pain management strategies to include chiropractic treatment and referrals.

While the chiropractic profession has a history in BPS-based interventional strategies, there has been little to no research addressing best practices for prioritizing the importance of psychosocial factors in the chiropractic field.9 The Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE) specifies a meta-competency in health promotion for chiropractic training programs to address, which includes “recognition of the impact of biological, chemical, behavioral, structural, psychosocial and environmental factors on general health.”9,10 However, little is known about the perceptions and implementation of BPS elements, both in chiropractic training and clinical practice. Even less is known about how these BPS strategies in chiropractic care may underscore effective pain management and positive patient outcomes.

Understanding the relationship between psychosocial factors and pain outcomes is important for establishing the utility of chiropractic care in interdisciplinary pain management. The objective of the current study was to begin to address these gaps by comparing perceptions between chiropractic patients and student providers at a teaching clinic across psychosocial features of care that are regularly implemented in BPS-informed management. Additionally, we sought to compare perspectives between patients and student providers on assessments on pain, affective and cognitive comorbidities, and overall perceptions of symptom burden.

Methods

Participants

All survey participants were recruited through the onsite main campus clinic at Parker University (Dallas, Texas). All current patients in a Parker University affiliated clinic were eligible to complete the Patient Survey. Student interns approved to see patients in their 8th, 9th, or 10th trimester in a Parker University affiliated clinic or on clinical rotation were eligible for completion of the Student Provider Survey. All procedures, forms, and questions used in this study were approved by the Parker University institutional Review Board (PUIRB-2021-12).

Survey

Study data were collected and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Parker University.11,12 Each survey (1 for patients and 1 for providers) was designed to administer analogous questions to both patients and providers through a combination of matching, adjusted list-selection, Likert and numerical scale, and open-ended questions. All survey responses remained entirely anonymous and were not patient-provider matched.

Patient Survey: A copy of the patient survey can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Patients provided general treatment information: demographics; reason for clinic visit; average numeric pain in the past week, 3 months, and 6 months (1 – no pain to 10 – maximum pain); comorbid affective and cognitive symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depression, stress, dysfunctions in memory/learning/executive function, sleep disturbances, and fatigue); information on in-clinic management of these symptoms and/or outside referrals; and provided the number of clinic visits in the past week and 3 months. Patients were also asked to rate their perceptions of their pain and care using a 1-5 Likert scale, as well as provide their perception of whether their provider addressed recovery outlook, control over own life, control over pain/injury, and support received from family and friends in their treatment plan.

Student Provider Survey: A copy of the patient survey can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Student providers provided personal demographic information, information about general injuries/diseases treated, average numeric rating of pain their patients presented with (1 – no pain to 10 – maximum pain), comorbid affective and cognitive their patients most commonly present with, their management strategies for these comorbidities (i.e. in-clinic management and/or outside referral), and average number of appointments with an individual patient across a single week and 3 months. Providers were also asked to rate their beliefs on patient perceptions using a 1-5 Likert scale, and detail if factors such as recovery outlook, injury and pain agency, and familial support were addressed.

Statistical Analysis

After data collection, survey responses were compiled and descriptively evaluated. Free responses were qualitatively evaluated to establish clinical characteristics. Patient pain scores were averaged across all reporting timelines (past week, 3 months, 6 months) to generate a global patient pain score. An independent samples t-test was used to assess differences in global average pain scores as reported by student providers and patients. To evaluate if there were differences in the reporting of affective and cognitive comorbidities between student providers and patients, Pearson Chi-Squared or Fisher’s Exact tests were used. Affective and cognitive global symptom burden was evaluated by comparing means of the total number of symptoms reported between groups using an independent samples t-test. To determine if there were differences in perceptions on whether biopsychosocial factors were managed in clinic, Pearson Chi-Squared test was used. To determine differences between patient and provider perspectives on reported pain and perceptions of social support, recovery, individual agency, and control over pain/injury, all assumptions were met, and a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used. Linear regressions were used to assess relationships between biopsychosocial outcomes, symptom burden, and pain ratings in both patients and providers.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics for both patients and student providers are presented in Table 1. A total of 30 patients completed the survey, most of which were male (56.66%), white (66.66%) and non-Hispanic (83.33%). On average, patients were 29.63 (SD = 10.69) years old, and all had previously completed at least a 4-year college degree. A total of 21 student providers completed the survey, with a mean age of 28.43 (SD = 4.14) years old. Providers were also largely male (71.42%), white (80.95%), and non-Hispanic (95.23%).

Patients primarily presented with musculoskeletal complaints. Patients frequently reported comorbid presentations, most common of which were shoulder pain (23.33%), low back pain (16.66%), unspecified back pain (16.66%), general musculoskeletal pain/injury (16.66%), and neck pain (13.33%). Similarly, student providers reported most commonly seeing generalized musculoskeletal complaints (47.61%), low back pain (28.57%), and extremity pain (23.81%). On average, patients reported having been treated in-clinic once in the past week (M = 1.00, SD = 0.70), and providers also report seeing the same individual at a similar rate (M = 1.86, SD = 0.79). In the past 3 months, patients reported an average of 8.6 (SD = 7.44) in-clinic treatments while student providers reported 15.05 visits (SD = 7.50) (Table 2).

Pain and Comorbidities

On a scale of 1-10, patients reported an average pain level of 3.62, (SD = 1.67). Specifically, patients reported a pain level of 3.27 (SD = 1.82) in the past week, 3.6 (SD = 1.94) in the past 3 months, and 4.0 (SD = 1.90) in the past 6 months. There was a trending effect of female patients reporting higher mean global pain scores than male patients, t13 = -1.81, p = .08. Providers reported that their patients presented with an average overall pain level of 4.65 (SD = 1.04) (Table 2).

Frequencies of comorbid symptoms reported by both patients and providers are presented in Table 2. The general presence of comorbid affective and cognitive symptoms was congruently reported between patients and providers, with 83.33% of patients reporting at least 1 comorbid symptomatology and 80.95% of providers reporting observing at least one comorbid symptom commonly among patients. Additionally, global severity of symptom burden was appropriately perceived by providers (M = 2.52, SD = 1.81) when compared to the degree of global severity reported by patients (M = 2.27, SD = 1.84), t(49) = .495, p = .622.

There was no statistical difference between patients and providers on reports of comorbid anxiety, depression, stress, memory loss, working memory, prospective memory, retrospective memory, decision making, or fatigue (p’s > .05). However, providers did significantly overreport sleep disturbances among patients, χ2 = 7.17, p = .007, with 71.4% of providers and only 33.3% of patients reporting sleep problems (Figure 1).

Outcomes: Pain and Biopsychosocial Perspectives

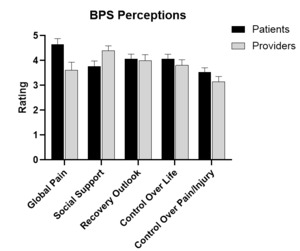

When evaluating differences between patients and providers, between group differences were found for average global pain reported by providers and patients, t(48) = 2.45, p = .018. Differences were also reported between groups on perceptions of social support, F(1,48) = 4.11, p = .05, ηp2 = .08. Providers reported perceiving higher average pain in patients (M = 4.65, SD = 1.04) than patients reported having experienced in the past week, 3 months, and 6 months (M = 3.62, SD = 1.67). While perceptions on whether social support was addressed in clinic did not differ between patients and providers, χ2 = 2.37, p = .12, providers did report lower average social support among patients (M = 3.80, SD = 1.51) than patients reported experiencing (M = 4.40, SD = 0.93) (Figure 2).

No differences were found between patients and providers on perceptions of recovery, F(1,48) = 0.14, p = .71, control over life, F(1,48) = 0.54, p = .47, or control over pain/injury, F(1,48) = 1.84, p = .18. Patients and providers also agreed that recovery outlook, χ2 = 2.36, p = .125, control over life, χ2 = .41, p = .52, and control over pain/injury, χ2 = 0.53, p = .82, were addressed as a part of their care (Figure 2).

Regression analysis identified a significant association between global patient pain ratings and ratings of control over their own injury when other perception ratings were controlled for, R2 = .361, p = .02. Patients with higher global pain ratings reported feeling less in control of their injuries (Table 3). A significant association was also found between patient biopsychosocial perspectives and patient reported symptom burden, R2 = .385, p = .01, where patients with higher symptom burden reported less feelings of control over their own life (Table 3). Provider perceptions of patient biopsychosocial outcomes were not significantly associated with perceptions of patient pain or symptom burden.

Discussion

The inclusion of chiropractic care in interdisciplinary pain management can be beneficial for improvements in patient pain, disability, and care satisfaction.5 The supplementation of standard medical care with chiropractic care has been associated with decreased opioid use in patients with pain,14–16 highlighting the advantages chiropractic practice offers for promoting nonpharmacological pain management. As is the case with any practitioner, the intentional use of the BPS framework for pain management substantially improves outcomes.17,18 In the case of chiropractic care, the BPS framework can be used to identify pain risk factors,19 harness psychosocial elements to maximize and personalize treatment,9,20 improve overall patient health behaviors,9,21,22 promote patient education,22 and offer support to patients through multimodal management.9,22 While much of chiropractic care and training inherently includes elements of the BPS framework,9 this study serves as the first to quantitatively assess perceptions of both student chiropractic providers and patients on how elements of the BPS framework are incorporated into pain management. Additionally, this study also serves as the first to compare provider and patient perspectives on pain, affective and cognitive comorbidities and symptom burden, and the influence of BPS perspectives on these factors.

In the current study, patients primarily presented with musculoskeletal complaints and indicated an average global pain score over the last week, 3 months, and 6 months of 3.62 on a 10-item numerical rating scale. These pain averages correspond with previous numerical rating scales from chiropractic patients with musculoskeletal pain.23 Additionally, we identified a trending effect of female patients reporting greater pain than male patients, which is also consistent with previous literature on chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions.24 However, we found an effect of student providers reporting perceiving greater pain severity in patients than patients reported experiencing on average. This effect was not expected, given that the fundamental pain bias shows that pain management practitioners typically assume the paradoxical position that patients over-report their pain.25 This effect may be unique to a chiropractic teaching clinic setting, and further research is needed to determine if this could also be the case in the clinics of licensed practitioners. However, since the chiropractic care model does not involve the liability of prescription analgesics25,26 it is possible there is less stigma surrounding the “trustworthiness” of patients’ pain reports.

Student provider perceptions of patient symptom burden were congruent with that which was reported by patients. Similarly, student providers accurately identified most common comorbid symptoms that patients presented with. Patients and student providers maintained similar perspectives on not only the inclusion of BPS elements in their care strategy, but providers also accurately identified their patients’ perceptions of recovery, individual agency, and control over their pain/injury. The accurate assessment of these factors are congruent with CCE meta-competencies, which include identifying “any present illness, systems review, and review of past, family and psychosocial histories.”10 These results may imply favorability towards chiropractic care in effectively implementing a BPS conceptual framework, given the ability or desire to utilize psychosocial factors in patient care is not always reflected in other healthcare disciplines.13,27–29

While providers did accurately assess many of the BPS factors impacting their patient’s pain experience, inconsistencies in perceptions were still identified. Student providers reported sleep disturbances among patients over two-fold more than what patients reported experiencing. While the exact reason for this discrepancy is unknown, this is a particularly interesting finding, as sleep deprived individuals often do not perceive themselves to be fatigued.30 It is possible that patients were unaware of the effects of their own sleep disturbances. Future inquiries should investigate this phenomenon as sleep deprivation can pose a serious health risk across a multitude of tasking and physiological functions.30,31 Providers also reported lower social support among their patients than patients reported experiencing. Accurate assessment of social support in patients is vital, because social support affects clinically meaningful pain responses and outcomes,32–34 even in the chiropractic population.35

Limitations

There are several limitations to note for this study that should be considered both for data interpretation and future methodological considerations. Patient and student provider responses were not matched in this study, which could introduce incongruencies in care perceptions. Future studies should aim to employ a matched-pairs design to offer maximum clarity in assessing patient and provider perceptions. To further promote clarity, future data collection should incorporate measures of symptom severity and satisfaction in management to maximize the understanding of health outcomes. In this study, there was the potential for student provider responses to be biased towards care plans that included BPS factors due to the recency of training.

CONCLUSION

Future work should look to include practitioners across a multitude of career stages to account for this potential effect. Additionally, both the patient and provider samples reported here were demographically biased – it is a necessity for future work to include a sample of diverse perspectives and to ensure the assessment of health equity in care. Similarly, future designs should incorporate larger sample sizes to offer a more powered perspective on the use of the BPS framework in chiropractic care. Finally, enrollment did not differentiate between chronic and acute pain patients. As such, the resolution of this study is limited in demarcating any potential differences in these 2 populations as it relates to perceptions of care, as well as providers outlooks on these groups. More specific studies focusing on one group or the other would offer greater clarity in regard to this issue.