INTRODUCTION

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is a varied collection of genetic connective tissue disorders, arising from gene mutations.1 The various forms of EDS have been classified in several different ways. Originally, 11 forms of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome were named using Roman numerals to indicate the types (type I, type II, etc.).1 In 1997, researchers proposed a simpler classification (the Villefranche nomenclature) that reduced the number of types to six and gave them descriptive names based on their major features.1 In 2017, the classification was again updated to include rare forms of EDS that were more recently identified. The 2017 classification describes 13 types of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome that are listed in Table 1.1–6

EDS testing is performed by a variety of methods. Hypermobility testing is performed using the Beighton Scale as listed in Table 2.1 A standard score of 5 or more indicates generalized joint hypermobility. Skin biopsy can be used to identify histological conditions, and classical and dermatospraxis EDS are evaluated by observing the cardinal signs of EDS: skin hyperextensibility, easy bruising, subcutaneous spheroids, and molluscoid pseudo tumors in conjunction with shin biopsy.6 Echocardiography, MRI, and CT can be used to evaluate for cardiovascular problems including aortic dilatation and mitral valve prolapse, and MRI can demonstrate lesions in white matter congruent with EDS.6

There are several conditions commonly related to EDS, and patients are frequently diagnosed with POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome), gastrointestinal related issues, idiopathic scoliosis, fibromyalgia, hypothyroidism, and multiple dislocations.7,8 POTS is a minimally understood dysfunction of the cardiovascular autonomic system, primarily affecting young females, with POTS patients often reporting dizziness and palpitations.6

A close connection exists between the genetic factors and musculoskeletal symptoms associated with EDS. The condition includes tissue disorders that often manifest as joint hypermobility and tissue laxity. Recognizing EDS in a chiropractic setting can be difficult because its characteristic features may resemble common musculoskeletal issues. To pinpoint the root cause and tailor treatment plans, a thorough assessment involving the patient’s history, clinical evaluation, and collaborative diagnostics is essential. The genetic components of hEDS have been classified as an autosomal dominant and inherited disorder with familial occurrence. However the genetic etiology of hEDS is unknown, and prevalence rates are estimated to be 1–3% of the general population.8

EDS presents a challenge in chiropractic practice due to its impact on the balance between joint stability and mobility. This case report discusses a patient’s involvement with EDS, highlighting the challenges in diagnosing the condition and exploring how chiropractic care can play a role in its treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old female sought care for severe chronic neck and low back pain, migraines, and bilateral hip pain attributed to recurrent hip dislocations. She had a prior diagnosis of EDS as well as a family history of migraines, along with mitral valve prolapse, weekly or monthly recurring joint dislocations, and upper and lower extremity joint hypermobility.

The neck pain was reported to occur in the mid-cervical spine bilaterally and was described as achy and throbbing. It was constant and only partially relieved by ice or ibuprofen. The low back pain was described as stabbing with frequent radiation into the right hip and leg. The migraines reportedly occur with neck pain and often begin as right-sided suboccipital pain which then radiate over the top of her head and behind both eyes. The pain is rated at an 8/10 and the onset is often sudden, with no known triggers. Current medication included a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3. She reported moderate aerobic exercise 3 to 6 times per week and social alcohol consumption once every other week. She was married and in graduate school. Examination revealed restricted segments in the cervical, thoracic, and lumber spine, as well as bilateral sacroiliac joint hypermobility. Hypertonicity and myofascial trigger points of the suboccipital, scalene, and trapezius musculature was noted. Motor, sensory, and reflex testing was unremarkable.

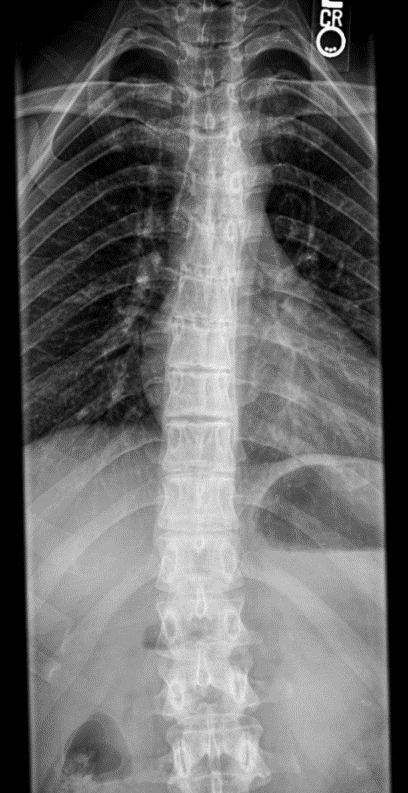

Delving further into her history revealed that she was originally diagnosed with hEDS by a prior chiropractor in 2015 as a result of examination findings which met the Beighton and Villefranche criteria. Repeated shoulder dislocations had led to the need for labral repair and shoulder stabilization surgery (bilateral surgeries in 2015 and 2019). She saw a rheumatologist in 2020 for joint pain and was further diagnosed with Hypermobile, Classical, Cardiac-Valvular, and Arthrochalasic types of EDS. Comorbid conditions of POTS and Raynaud’s syndrome were also diagnosed. She was referred for head and upper cervical MRI with and without contrast to rule out tumors or other lesions in the brain and brain stem. MRI revealed a mild Chiari Type 1 malformation but was otherwise clear of lesions. Radiographs were taken of the hands, feet, knees, lumbar spine, and pelvis. The patient was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and spina bifida occulta of L5 and S1 along with hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine, demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Additional radiographs were taken in 2022 after she was involved in a motor vehicle accident (figures 3 and 4). The accident provoked further low back and migraine symptoms while creating numbness and radicular symptoms in her right leg. Additional diagnoses were made of Schuermann’s disease and kyphoscoliosis, with a right curvature from T6-L2.

Currently, she receives regular chiropractic care 2-3 times per week, consisting of low-force manipulations to restricted spinal segments using a variety of methods including manual, drop, and instrument assisted techniques, coupled with manual pressure release for myofascial trigger points in spinal as well as upper and lower extremity musculature. She experiences consistent pain relief after each visit, which is maintained for several days before symptoms return. This is in contrast to her reported outcomes of increased pain and inflammation that would often occur following forceful chiropractic manipulation in prior years. In an attempt to improve function and lengthen the time period of symptom relief, she has also been given low-weight, low-intensity strengthening exercises with exercise bands and free weights for muscles in both her trunk and extremities.

DISCUSSION

Ehlers-Danlos patients are commonly treated with anti-inflammatory drugs or splinting methods that are not used to treat the condition, but rather to manage symptoms and maintain lifestyle. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos can be missed in young people and females of any age due to being viewed as “flexible” instead of hypermobile. Patients with hypermobile joints are at higher risk of experiencing joint dislocation.9 The most important aspect of management is prevention because each injury raises the chances of recurrence and complications like osteoarthritis. Prevention involves thorough patient education about the importance of avoiding high-risk activities such as heavy weight training or contact sports.6

Repeated joint injuries can lead to early-onset osteoarthritis and potentially a multitude of orthopedic procedures, especially in hypermobile and classical subtypes. While these procedures may be warranted based on the insult, the understanding is that the laxity of the affected connective tissue increases over time, which may predispose to additional insult.10 Gentle low-force spinal manipulative therapy techniques performed by chiropractic physicians might offer a safe and effective option for hEDS patients. While convention dictates that manipulation of hypermobile structures is generally contraindicated, the role of low-force chiropractic manipulative techniques combined with soft tissue therapies or exercise has shown some promise at decreasing pain in hEDS patients.11 With the array of functional difficulties, musculoskeletal symptoms, and consequent physical deconditioning that individuals with EDS may encounter, exercise and rehabilitation are crucial elements of managing the condition.12

Because the molecular basis of hEDS is unknown, there is currently no confirmatory laboratory test to diagnose this specific subtype of EDS.13 However, a positive family history, with 1 or more first-degree relatives independently meeting the hEDS diagnostic criteria, can also be used to determine a diagnosis.13 The patient’s mother and younger sister both had a diagnosis of hEDS (diagnosed from Beighton and Villefranche criteria). Genetic factors are also included in presentations of spina bifida occulta, as well as other spinal pathologies associated with EDS including segmental instability and kyphosis, Chiari malformation, kyphoscoliosis, problems with wound healing, and bleeding disorders.14

Our patient has been treated using various manual manipulative therapies for over a decade, experiencing beneficial outcomes for many of her pain complaints. The patient reports temporary symptom relief from chiropractic care, responding well to gentle low-force manipulations with diverse techniques. However, reported relief typically lasts only 2-3 days before symptoms return. A goal of this paper is to promote discussion of how chiropractic care may be beneficial in symptomatic control for hypermobile patients without causing additional inflammatory response or injury.

This case also emphasizes the need for an appropriate and thorough history of patients with connective tissue disorders. The history for these patients must include a focus on prior surgeries, dislocations, and hypermobile areas of the body. This can aid the practitioner in choosing appropriate manipulation techniques as well as those that should be avoided in certain regions.

Limitations

This is a single-patient case report, and the results may not be generalizable to other individuals presenting with similar conditions.

CONCLUSION

In terms of intervention, managing EDS necessitates an approach that considers the patient’s functionality and quality of life beyond addressing immediate musculoskeletal concerns. Chiropractors should aim to enhance joint stability, while alleviating pain and promoting overall well-being. This case report emphasizes a focused integrated treatment strategy while shedding light on the intricate relationship between musculoskeletal health and EDS.

CONSENT

Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.