INTRODUCTION

For over a decade, educators have expressed concerns about declining attendance in undergraduate medical lectures.1 In a study published in Medical Science Educator, Emahiser et al. surveyed first and second-year medical students to explore their perceptions, perspectives, and motivations regarding class attendance.2 The primary reason for missing class was the perceived efficiency of viewing lectures online, followed by dissatisfaction with the professors’ teaching style. Romer conducted an analysis and found that absenteeism is a significant issue in undergraduate economics courses across major American universities.1 He highlighted a robust statistical relationship between absenteeism and poor academic performance, suggesting a causal link.

Romer advocated for mandatory attendance in additional classes to further validate this hypothesis.

A parallel investigation by Kirby and McElroy et al. indicated that university classroom attendance positively impacted grades with diminishing marginal effects.3 The study also highlighted factors influencing lecture attendance rates, such as the number of hours worked and commuting distances exceeding 30 minutes to reach the university. The authors concluded that Irish educators consider incorporating first-year grades into the overall degree grade calculation to boost student attendance.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a rapid transition to online learning, fundamentally altering higher education by enforcing self-directed, virtual coursework. While this change presented challenges for universities and students, the abrupt shift to self-directed online courses has undeniably altered the landscape of higher education and may have adversely impacted the educational experience at many institutions.4,5 This shift posed unique challenges, particularly for hands-on disciplines like chiropractic, where skill acquisition heavily relies on in-person practice. These changes underscore the need for educational institutions to balance traditional in-person methods with flexible online options to support skill-based training in healthcare programs.

As the pandemic subsided, some universities maintained their newfound flexibility in attendance policies, allowing students to attend classes as they deemed fit. Zhao et al. argued that educators must make student autonomy and agency key to transforming pedagogy and school organizations.6 They further suggested that students will prosper by having more say in their learning and learning communities and that schools will have a unique opportunity to change due to COVID-19. They recommended that schools rearrange their schedules and places of teaching so that students can participate in different and more challenging learning opportunities simultaneously, regardless of their physical location.

In hands-on fields like chiropractic, physical therapy, and nursing, where physical interaction is a fundamental part of the job, student perception of classroom attendance could be an important factor influencing manual skill acquisition.4 This study explored student perceptions of the relationship between classroom attendance and academic performance in a sample of chiropractic hands-on labs at Parker University in Dallas, TX. The findings of this study could guide educational strategies in adapting to the “new normal” while ensuring the effectiveness of chiropractic training and similar fields.

METHODS

An electronic survey was conducted to gather student perceptions about the relationship between classroom attendance and academic performance in chiropractic technique courses. The Parker University Institutional Review Board approved this study (PU-IRB-2023-19).

Before completing the survey, participants provided electronic informed consent, and all responses were anonymized to protect confidentiality.

Participant Selection

Trimester 4 students were selected as the focus of this study because they are at a critical point in the Doctor of Chiropractic program, having completed the foundational coursework and now transitioning into more clinically focused training. Students who participated in this survey were all enrolled in Trimester 4 at the university and were eligible if they were over 18 years old. The decision to examine a single cohort also allowed for greater control over variables such as course content, instructor, and academic schedule. This homogeneity improves the reliability of the data and makes it easier to assess the relationship between classroom attendance and academic performance.

Data Collection

The survey was distributed through REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA), a secure, web-based survey platform.7,8 Invitations were extended via email and in-class announcements, with additional outreach through digital flyers and campus newsletters.

Participation was voluntary, and all responses were anonymous to protect confidentiality. Participants provided electronic informed consent, and all responses were anonymous to protect confidentiality.

Participants were provided with information about the study’s title and purpose and were informed that participation was voluntary, and all responses would be kept confidential and anonymous.

Before completing the survey, each participant signed an informed consent form electronically outlining the study’s objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and risks. No students were incentivized to participate in the survey.

The survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Any identifying information was separated from the collected data to safeguard participant anonymity. The data was securely stored and processed in REDCap and downloaded as de-identified info with access restricted solely to the research team.

Survey Instrument

The survey consisted of 19 questions designed to gauge students’ perceptions of the impact of classroom attendance on their grades. Each question was designed to assess students’ perceived importance of in-person lab attendance alongside their self-reported attendance patterns.

Investigators used previous studies to inform new questions. Questions included quantitative and qualitative aspects, and were segmented into several distinct sections:

-

Basic Information: This section captured essential demographic and academic details including trimester, GPA, gender, age, education level, work commitments, income, parental status, and international student status.

-

Lab Attendance: This section focused on assessing the regularity of lab attendance, identifying reasons for any absences, and documenting alternative methods of study when labs are missed.

-

Perceptions of Lab Attendance on Academic Performance: This section investigated students’ views on the significance of lab attendance in their professional development and its correlation with academic achievements. It also aimed to ascertain the skills or knowledge acquired in labs that enhance academic success. A copy of the survey is listed below:

Student Perception Survey on Lab Attendance and Academic Performance Introduction

This survey aims to understand your experiences and perspectives regarding attendance at chiropractic lab courses and its potential impact on academic performance. Your responses are invaluable in our ongoing research to improve the quality of our education. The survey should take no more than 10 minutes to complete, and your responses will be kept confidential.

Section 1: Basic Information

1. What is your trimester of study?

☐ 2nd trimester

☐ 3rd trimester

☐ 4th trimester

☐ 5th trimester

☐ 6th trimester

☐ 7th trimester

2. What is your current GPA? (If you are not comfortable sharing, please skip this question)

☐ <1.0

☐ 1.99

☐ 2.0 - 2.99

☐ 3.0 - 3.99

☐ 4.0

☐ Prefer not to answer

3. What is your gender?

☐ Female

☐ Male

☐ Transgender, non-binary, or another gender

☐ Prefer not to answer

4. How old are you (in years)?

☐ __

5. What’s the highest level of education that you have completed thus far?

☐ No college

☐ Associate’s degree

☐ Bachelor’s degree

☐ Master’s degree

☐ Doctoral degree

6. Do you work a job while attending Parker University? If yes, please select which one applies to you.

☐ 1-10 hours

☐ 11-20 hours

☐ 21-30 hours

☐ 31-40 hours

☐ 40+ hours

☐ I don’t work

7. What is your combined household income?

☐ < $10,000

☐ $10,000-$29,999

☐ $30,000-$59,999

☐ $60,000-$100,000

☐ $100,000-150,000

☐ >$150,000

8. Do you have any children?

☐ Yes

☐ No

9. Are you primarily responsible for taking care of your child/children while you are a student at Parker University, or is it a spouse / partner, or shared?

☐ I am the primary caregiver

☐ My spouse / partner is the primary caregiver

☐ Care is shared

☐ Another family member or person is the primary caregiver

☐ N/A

10. Are you an international student?

☐ Yes

☐ No

If yes, indicate country:

☐ __

Section 2: Lab Attendance

11. On average, how often did you attend in-person lab sessions last trimester?

☐ I attended all scheduled lab sessions.

☐ I missed one lab session

☐ I missed two lab sessions

☐ I missed three lab sessions.

☐ I missed four or more lab sessions

12. What are the primary reasons for any missed in-person lab sessions? (Select all that apply)

☐ Personal obligations (e.g., work)

☐ Illness or physical health issues

☐ Mental health issues

☐ Lack of perceived value from the sessions

☐ Family obligations

☐ Need to study for other courses

☐ I don’t like the way the material is presented in the lab

☐ I can go over the recorded lab videos more efficiently

☐ Do not like a certain professor’s teaching style

☐ I prefer different learning methods

☐ Other, please specify

13. When you do not attend in-person labs, what do you do instead to learn and prepare for practical assessments, if anything?

☐ Create study guides based on learning objectives

☐ Study guides posted by classmates and or upper tri students

☐ Study posted PowerPoints/ Materials/ Lab Guides

☐ Watch recorded lab videos

☐ Read assigned textbook readings

☐ None of the above

☐ Other, please specify

14. If you attend in-person labs, what do you do before to prepare, if anything?

☐ Preview the material briefly

☐ Preview the material extensively

☐ Read assigned textbook chapters

☐ Watch lab videos

☐ Nothing

☐ Other, please specify

15. When you attend in-person labs, which of the following do you do in the lab? Select all that apply.

☐ Concentrate on content being demonstrated by professor

☐ Practice setups/adjustments

☐ Take notes while in the lab

☐ Ask questions

☐ Other, specify

Section 3: Perception of Lab Attendance and Academic Performance

16. On a scale of 1-5, how important do you feel in-person lab attendance is to your future development as a chiropractor? (1 – not important at all, 5 very important

☐ 1

☐ 2

☐ 3

☐ 4

☐ 5

17. On a scale of 1-5, how strongly do you believe in-person lab attendance relates to academic performance?

☐ -5 (strong negative relationship – lab attendance has a strong negative influence on academic performance)

☐ -4

☐ -3

☐ -2

☐ -1

☐ 0 - no relationship between lab attendance and academic performance

☐ +1

☐ +2

☐ +3

☐ +4

☐ +5 (strong positive relationship – lab attendance has a strong positive influence on academic performance)

18. In your opinion, what skills or knowledge (if any) is gained from the in-person lab sessions contribute to your academic performance?

__

Section 4: Additional Comments

19. Please provide any additional comments or suggestions regarding the impact of in- person lab attendance on academic performance.

☐ __

Thank you for your time and valuable input. Your responses will greatly assist in our ongoing effort to enhance the learning experience at our institution.

By clicking the ‘Submit’ button, you agree to the use of your responses for research purposes. Your responses will remain anonymous.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated: Frequencies and percentages of various response categories, such as GPA ranges, attendance rates, and reasons for absences. Visual representations in charts and figures were created to illustrate these relationships and distributions clearly.

Below is a description of all variables from the study, including how they were measured and any summary statistics. Based on the survey document, the following variables were collected:

Section 1: Basic Information

-

Trimester of Study:

-

Variable: Trimester level (e.g., 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc.)

-

Purpose: Identifies which stage students are at in their program.

-

Summary Stats: Frequencies for each trimester level could provide insights into which groups of students participated.

-

-

Current GPA

-

Variable: Self-reported GPA (ranges: <1.0, 1.99, 2.0-2.99, 3.0-3.99, 4.0, or “Prefer not to answer”)

-

Purpose: To correlate academic performance with attendance.

-

Summary Stats: Percentage distribution across GPA ranges (e.g., 1.6% had a 4.0 GPA, 77.8% had a 3.0 GPA, etc.)

-

-

Gender

-

Variable: Gender identity (Female, Male, Transgender/non-binary/other, Prefer not to answer)

-

Purpose: Collect demographic information for subgroup analysis.

-

Summary Stats: Percentage breakdown (e.g., 52.4% male, 46.2% female, 1.4% other or prefer not to answer).

-

-

Age:

-

Variable: Age in years (numeric).

-

Purpose: Age as a potential factor in attendance patterns or academic performance.

-

Summary Stats: Mean, median, and range of ages if available.

-

-

Highest Education Level Completed

-

Variable: Highest level of education (e.g., No college, Associate’s, Bachelor’s, Master’s, Doctoral).

-

Purpose: To understand the educational background of participants.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency and percentage distribution across education levels.

-

-

Employment Status

-

Variable: Hours worked per week (e.g., 1-10 hours, 11-20 hours, etc., or “I don’t work”)

-

Purpose: To examine the relationship between employment and attendance.

-

Summary Stats: Percentage distribution of employment status (e.g., 43.8% indicated employment).

-

-

Household Income

-

Variable: Combined household income (ranges: <$10,000 to >$150,000).

-

Purpose: Socioeconomic factors that could influence attendance.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency distribution across income ranges.

-

-

Parental Status and Caregiving Responsibility

-

Variable: Presence of children and caregiving responsibility (primary caregiver, shared care, etc.)

-

Purpose: To assess if caregiving responsibilities affect attendance.

-

Summary Stats: Percentage of students with children and their caregiving roles.

-

-

International Student Status

-

Variable: International student status (Yes/No).

-

Purpose: To explore if international status correlates with attendance patterns.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency of international versus domestic students.

-

Section 2: Lab Attendance

-

Average Lab Attendance:

-

Variable: Number of labs attended last trimester (all, one missed, two missed, etc.)

-

Purpose: To gauge attendance consistency and potential impact on performance.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency and percentage for each attendance category (e.g., attended all labs, 1 absence, etc.)

-

-

Reasons for Missing Labs

-

Variable: Reasons for absence (e.g., illness, personal obligations, family obligations, etc.)

-

Purpose: To identify factors that commonly lead to absences.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency and percentage for each reason (e.g., 41.1% for illness/physical health, 27.4% for studying for other courses, etc.)

-

Section 3: Study Practices When Not Attending Labs

-

Alternative Study Methods When Missing Labs:

-

Variable: Resources used if a lab is missed (e.g., lab videos, posted materials, study guides).

-

Purpose: To determine which resources students, rely on when they miss labs.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency and percentage for each alternative (e.g., 68.5% used lab videos, 41.1% used posted materials).

-

Section 4: Preparation Practices Before Attending Labs

-

Preparation Practices When Attending Labs:

-

Variable: Preparation methods before attending labs (e.g., briefly preview, watch lab videos).

-

Purpose: To understand how students prepare for labs to maximize learning.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency and percentage for each method (e.g., 54.8% briefly previewed material, 44.5% watched lab videos).

-

Section 5: Perception of Lab Attendance Importance

-

Perceived Importance of Lab Attendance for Future Development:

-

Variable: Perceived importance of in-person lab attendance to chiropractic development (1-5 scale, with 5 being very important).

-

Purpose: To assess students’ belief in the value of attendance for skill development.

-

Summary Stats: Percentage breakdown for each rating level (e.g., 68.5% rated 5/5, indicating high importance).

-

-

Perception of Lab Attendance’s Impact on Academic Performance

-

Variable: Perceived relationship between lab attendance and academic performance (scale from -5 to +5).

-

Purpose: To measure how strongly students believe attendance affects grades.

-

Summary Stats: Frequency for each rating (e.g., 54.8% rated a strong positive relationship of 5/5).

-

Additional Comments

-

Open-Ended Feedback on Lab Attendance and Academic Performance:

-

Variable: Qualitative responses (open-ended comments).

-

Purpose: Gather insights and suggestions on lab attendance and its perceived effects.

-

Summary Stats: Content analysis for recurring themes (if analyzed).

-

RESULTS

The total number of responses from fourth-trimester students was 146 (n=146). Of these respondents, 52.4% identified as male, 46.2% as female, and 1.4% selected “other” or preferred not to specify their gender.

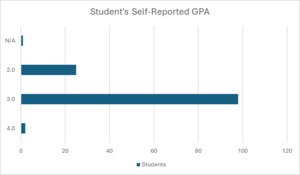

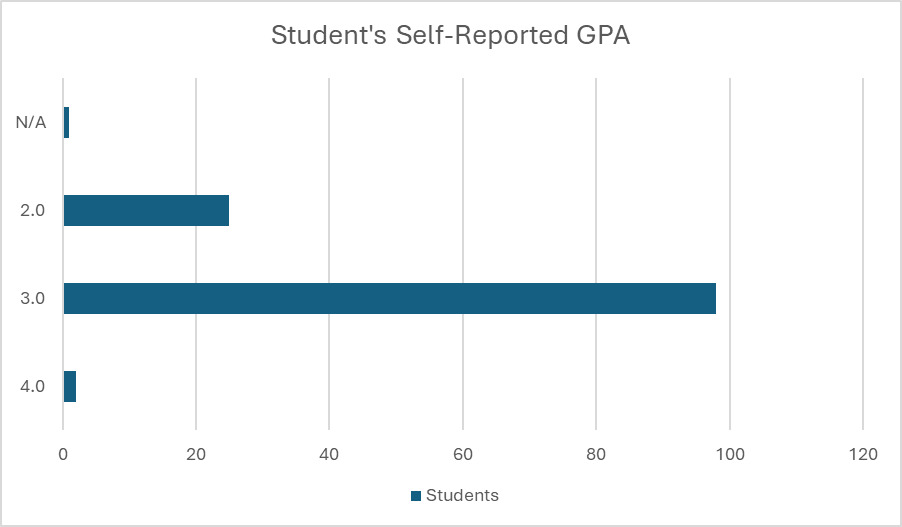

The self-reported GPA (Figure 1) distribution among respondents was as follows:

- GPA 4.0: 2 students (1.6%)

- GPA 3.0: 98 students (77.8%)

- GPA 2.0: 25 students (19.8%)

- Not reported (N/A): 1 student (0.8%)

These results show a high concentration of students with a GPA of 3.0, suggesting an overall strong academic performance among respondents.

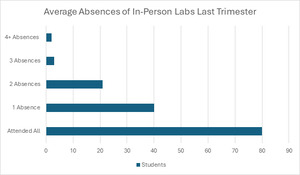

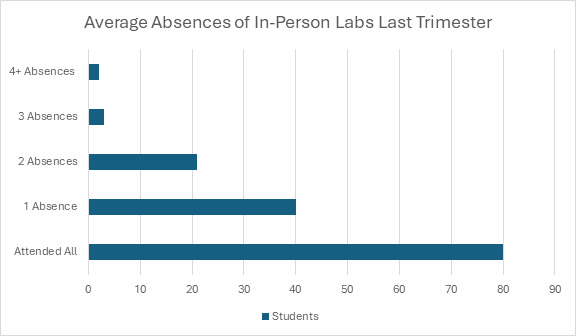

Attendance rates (Figure 2) for in-person labs from the last trimester varied:

- Attended All Labs: 80 students (54.8%)

- 1 Absence: 40 students (27.4%)

- 2 Absences: 21 students (14.4%)

- 3 Absences: 3 students (2.1%)

- 4 or More Absences: 2 students (1.4%)

The majority of students attended all lab sessions, indicating a strong commitment to in-person learning.

Students reported various reasons (Figure 3) for missing in-person labs, primarily related to personal and academic obligations:

- Illness / Physical Health: 63 students (44.1%)

- Studying for Other Courses: 38 students (26.6%)

- Family Obligations: 24 students (16.8%)

- Mental Health: 22 students (15.4%)

- Personal Obligations: 28 students (19.6%)

- Lack of Perceived Value: 10 students (7.0%)

- Material Presentation Style: 2 students (1.4%)

- Recorded Lab Material is Sufficient: 14 students (9.8%)

- Professor’s Teaching Style: 5 students (3.5%)

- Prefer Different Learning Methods: 3 students (2.1%)

- Other: 26 students (18.2%)

These findings indicate that health issues and academic workload are the primary factors influencing lab absences.

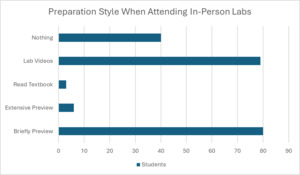

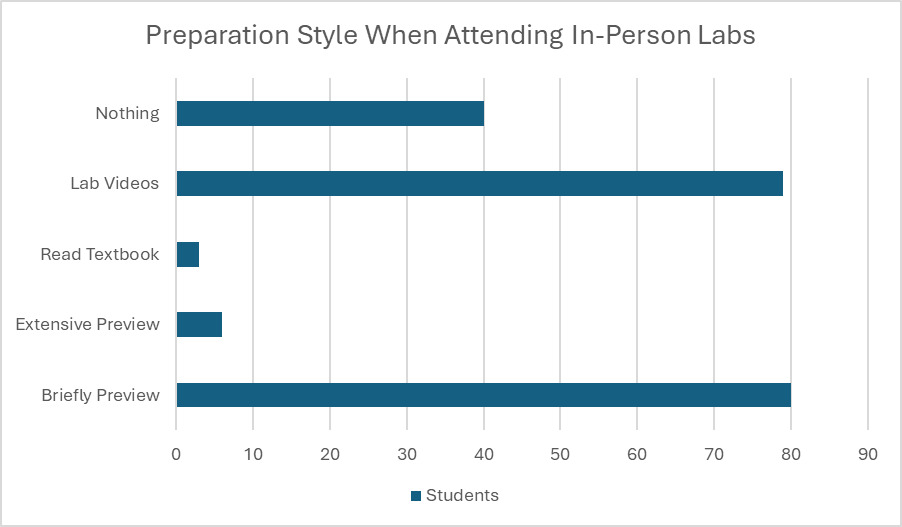

Students reported different methods of preparation (Figure 4) before attending in-person labs:

- Nothing: 44 students (30.6%)

- Lab Videos: 79 students (54.9%)

- Read Textbook: 3 students (2.1%)

- Extensive Preview: 6 students (4.2%)

- Briefly Preview: 80 students (55.6%)

The most common preparation methods (Figure 5) were briefly previewing the material (54.8%) and watching lab videos (44.5%), suggesting that students prefer concise and accessible materials for lab preparation.

When students missed labs, they utilized various resources to compensate:

- Lab Videos: 108 students (76.6%)

- Posted Material: 87 students (61.7%)

- Use Study Guides: 36 students (25.5%)

- Create Study Guide: 22 students (15.6%)

- Textbook: 9 students (6.4%)

- None: 13 students (9.2%)

- Other: 7 students (5.0%)

Lab videos were the most commonly used resource by students who missed labs, highlighting the importance of recorded content in helping students stay up to date.

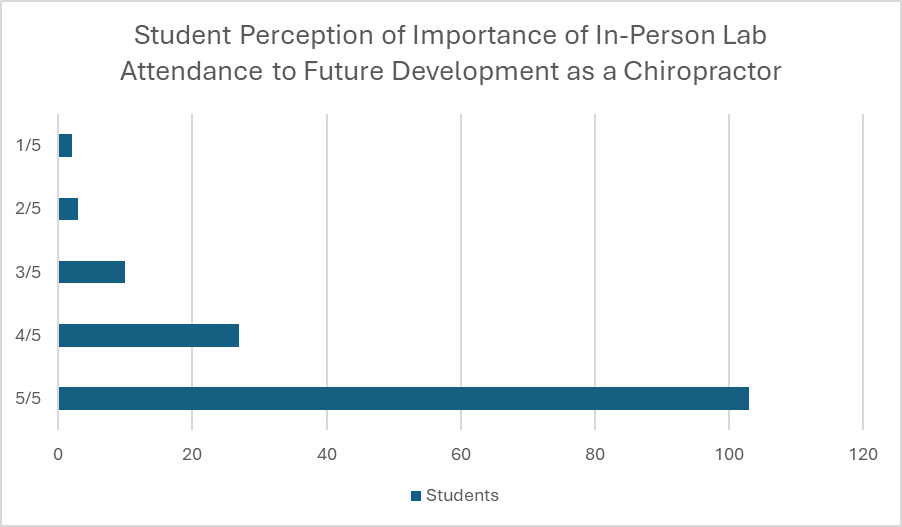

Students rated the importance of in-person lab attendance for their future development as chiropractors on a scale from 1 to 5 (Figure 6):

- 5/5 (Strong Importance): 103 students (71.0%)

- 4/5: 27 students (18.6%)

- 3/5: 10 students (6.9%)

- 2/5: 3 students (2.1%)

- 1/5 (Weak Importance): 2 students (1.4%)

A substantial majority (68.5%) rated in-person attendance as highly important (5/5), underscoring students’ belief in the value of hands-on practice for their professional growth.

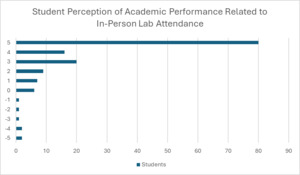

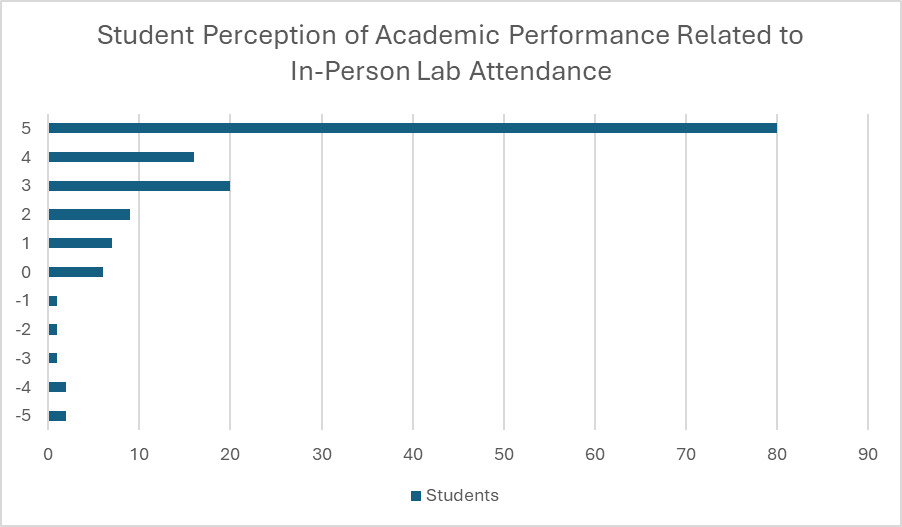

Students also rated the perceived impact of lab attendance on their academic performance on a scale from -5 to +5 (Figure 7):

- 5/5 (Strong Positive Relationship): 80 students (55.2%)

- 4/5: 16 students (11.0%)

- 3/5: 20 students (13.8%)

- 2/5: 9 students (6.2%)

- 1/5: 7 students (4.8%)

- 0/5 (No Relationship): 6 students (4.1%)

- Negative Relationship (-1 to -5): 7 students (4.8%)

More than half (55.2%) rated a strong positive relationship (5/5), suggesting that most students perceive a significant benefit of lab attendance on their academic performance.

Overall Summary

The results indicate that most students:

-

Maintain high attendance rates and strong GPAs.

-

Value in-person lab attendance as crucial for both academic performance and future professional development.

-

Use lab videos and other digital resources when they cannot attend in-person labs.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide valuable insights into the perceptions of Trimester 4 chiropractic students regarding the relationship between classroom attendance and academic performance in hands-on technique courses. With a response rate of 62.7%, we gathered data from a significant portion of the cohort, which enhances the reliability of the findings, though some caution is needed in generalizing the results to the entire student population.

The choice to focus on Trimester 4 students allowed for greater control over variables such as course content, instructor, and academic schedule, minimizing external influences on the data. This homogeneity improves the internal validity of the study, enabling a clearer understanding of the relationship between attendance and academic performance. The students in this cohort are at a pivotal point in their chiropractic education, transitioning from basic sciences to more clinically focused training, where the development of hands-on skills becomes critical.9 As such, their perceptions are particularly relevant for understanding the impact of attendance on academic and professional development.

The findings are consistent with previous research in healthcare education, which highlights the importance of classroom attendance, particularly in courses with a significant hands-on component.10 While many students recognized the value of attendance, the main reasons for absences—such as illness and prioritization of other academic commitments—suggest the need for academic support systems that accommodate the complexities of student life.

Consistent with prior research in medical and educational fields, our results highlight a strong student belief in the positive relationship between attendance and academic success, especially in hands-on chiropractic technique courses. The study found that most students believe in the positive impact of in-person lab attendance on performance, which resonates with the broader academic discourse on this topic.10 These findings contribute to the existing body of research by offering a specific insight into the perceptions and behaviors of chiropractic students regarding classroom attendance and academic performance.10 Most participants deemed regular attendance crucial for professional development, aligning with educational theories prioritizing consistent classroom engagement for effective learning, particularly in hands-on disciplines.11

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on educational dynamics is evident, with a shift toward online learning. This study reflects this transition, highlighting a preference among some students for online formats.12 The ability to learn wherever, whenever, seems like a very enticing option. It allows the students with families to not worry about childcare, and those who live far away the ability to save time on their commute. If they have other obligations such as a job, family caretaker, or errands it allows them to schedule their time when it makes the most sense for the individual student. However, the preference for in-person learning, especially in practical courses, remains a priority for students, suggesting a need for a balanced approach in healthcare education.13

The hands-on in-person labs provide an environment for education, remediation, and most importantly, practice. With hands-on skills the most important aspect is true practice on the material. While some courses may provide videos and written material, psychomotor skills require repetition, and labs allow students to have multiple practice partners. For students without a large group to practice with, these labs may be the only time they find it comfortable to work with others. In these sessions, the professor also is more easily accessible to either address questions or find areas of confusion in their students before the day of exams.

With limited space and timing for ever increasing class sizes, the ability to have a flexible schedule for students becomes more daunting. Sickness happens, car accidents happen, real life happens, usually at the most inopportune moment. Without online options, the only option is to miss the content and view any material the professor has online, if any. One missed lab due to illness or other circumstances can snowball into a lack of understanding for the following labs and negatively affect the student’s overall understanding of the course. Student absenteeism, driven by illness and academic pressure, indicates a need for holistic academic support systems.14

While some students may appreciate these flexible policies, the absence of mandatory attendance challenges faculty in fostering student engagement and knowledge retention. In hands-on professions such as chiropractic, physical therapy, nursing, and various medical fields, attending hands-on classes appears crucial for gaining optimal practical experience and firsthand content delivery. The evolving educational context due to COVID-19 highlights the need to understand chiropractic students’ perceptions. This understanding is crucial as it may illuminate how changes in attendance policies and teaching formats affect students’ learning experiences and outcomes.

The traditional academic framework in chiropractic education integrates comprehensive coursework in both basic and clinical sciences with substantial hands-on training. Students commence their studies with foundational courses in anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, and pathology, which are critical for a thorough understanding of human biology. This foundational knowledge is further enhanced through clinical sciences, including radiology, neurology, and orthopedics, which impart essential diagnostic and treatment skills.

Hands-on laboratory sessions are a vital component of the curriculum, allowing students to practice techniques such as palpation, spinal adjustments, and extremity manipulation under expert supervision. At Parker University, the Doctor of Chiropractic program spans 10 trimesters, beginning with an intensive focus on Basic Sciences—encompassing anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, and other similar courses. As the program progresses, the emphasis shifts toward Chiropractic Sciences, including but not limited to clinical biomechanics, static and motion palpation, analysis and adjustment techniques, and physiotherapy, as well as Clinical Sciences such as neurology, clinical orthopedics, imaging, and differential diagnosis.

The final year of the program, encompassing trimesters 8 through 10, is primarily dedicated to clinical practice. During this period, students, referred to as interns, apply their skills in clinical settings, treating both peers and actual patients. Additionally, students have the opportunity to participate in a Clinic-Based Internship (CBI) during their final trimester, where they work alongside practicing chiropractors, gaining invaluable experience in patient care under direct supervision. Clinical internships and externships offer real-world experience, allowing students to treat patients in supervised settings.

Other courses within the Doctor of Chiropractic degree at Parker university include professional development courses which cover ethics, business management, and licensure preparation, ensuring graduates are ready for the professional environment. This blend of theoretical knowledge and practical training ensures chiropractic students are well-prepared for clinical practice. Additionally, research methodology courses and capstone projects emphasize evidence- based practice, preparing students to contribute to the scientific community.

At Parker University, each technique class comprises both a lecture and a laboratory component, providing students with the opportunity to develop their hands-on skills. These technique labs focus on a range of practices, including static and motion palpation, as well as various adjustment methods such as diversified, Gonstead, activator, and Thompson techniques.

The curriculum varies by trimester, with students engaged in different numbers of technique courses. For instance, in the second trimester, students participate in two palpation classes, while in the third and fourth trimesters, they take one class dedicated to spinal adjustments and another focused-on extremity adjustments. This series of adjusting classes continues through the seventh trimester, with the option to enroll in additional elective courses on adjusting techniques and soft tissue manipulation. Furthermore, students have access to instructor-led open labs and student- run clubs, allowing for supplementary hands-on practice beyond the structured curriculum.

Relationship Between Attendance and Academic Performance

Most participants indicated that regular in-person attendance was “Very Important” for their development as chiropractors. This aligns with traditional educational theories that emphasize the importance of regular classroom engagement for effective learning, particularly in practical, hands-on disciplines (physical hands-on learning source).15 Students’ high valuation of attendance reinforces the notion that in-person learning experiences are crucial in fields requiring practical skills, such as chiropractic practices.

Student Absenteeism; Causes & Solutions

The study also highlights the reasons behind student absenteeism, with illness and prioritizing studies for other classes being the most common. This finding suggests a need for more holistic academic support systems to accommodate students’ health and cross-curricular study needs, offering more hands-on opportunities to make up lab sessions missed from various life situations.

With the surge of research and development into AI, augmented reality could provide a bridge between in-person and online learning. As the tools expand, it could allow students to participate in a more hands-on environment, while still allowing the flexibility of time. This is limited by the instructor and institution’s ability to create and apply these modules to the standard of in-person lab, but it would provide an avenue for a more advanced hybrid learning environment.

Course load also seems a factor, as illness and studying for other courses are major factors to why students do not attend lab sessions. Whether that be too many hours taken in a program, or illness from pushing themselves too far trying to attain high marks in all courses. If the program offered a lower courseload, longer graduation timeline path, it may allow students to choose the path that allows for more time per course.

Limitations and Implications

Despite the insights gained from this study, there are limitations. The response rate, while relatively strong at 62.7%, does not fully meet the ideal threshold for broad generalizability, typically considered to be 70-80%. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, as actual attendance records and academic performance metrics were not collected. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating objective data, such as GPA and attendance logs, to compare with student perceptions and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between attendance and academic success.

While this study provides insight into the perceptions of chiropractic students, its scope is limited to a single institution, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study does not account for potential external variables that might influence academic performance. The reliance on self-reported data might not fully capture attendance habits or performance outcomes. Further research could pull the true attendance records and grade averages from these students and see if their perceptions are validated. Studies could also expand to include multiple chiropractic schools and potentially integrate objective measures of attendance and performance for a more comprehensive understanding.

The study’s implications suggest a multifaceted approach may enhance chiropractic education. The students’ consensus on the importance of attendance must be taken into consideration with real-world limitations of sickness, and obligations outside of class as well as others. Given the importance of classroom attendance in hands-on courses, there is an opportunity to reevaluate and redesign the curriculum, emphasizing practical engagement. This aligns with the emerging need for hybrid educational models that blend in-person and online learning, catering to varied student needs and circumstances. Additionally, the reasons behind student absenteeism, such as health concerns and academic pressures, underline the necessity for robust support systems, including mental health services and academic counseling. These strategies, combined with high attendance, are crucial for professional development and may prompt the refinement of attendance policies to foster consistent participation.

Finally, these findings open avenues for further research into the benefits of various teaching methods in healthcare education, particularly in responding to challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. This comprehensive approach could significantly enhance the learning experience and outcomes in chiropractic and related fields.

CONCLUSION

This study sheds light on the perceptions of Trimester 4 chiropractic students regarding the importance of classroom attendance in hands-on technique courses. With a response rate of 62.7%, the findings provide a strong foundation for future research but should be interpreted with some caution regarding generalizability. Most students indicated that regular attendance is crucial for both academic performance and professional development, reinforcing the need for in-person learning in skill-based disciplines like chiropractic education.

Future studies should build on this work by incorporating objective measures of academic performance, such as GPA and attendance records, to validate student perceptions. Additionally, strategies to increase response rates, such as targeted cohorts and incentives for participation, should be employed to strengthen the generalizability of future findings. Overall, this research highlights the enduring value of attendance in chiropractic education and provides a basis for refining educational policies to support student success.

Funding, Sources, & Conflict of Interest

No funding was received. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

If you are interested in obtaining a copy of the survey used in this study, please feel free to contact us via email, and we will gladly provide you with a copy.