Introduction

Traffic-related pedestrian injuries are a growing public health threat worldwide. In 2024, the global economic burden of pedestrian and motor vehicle collisions involving both fatal and non-fatal crash injuries was estimated to approximate USD$1.8 trillion.1 In countries where the population relies on personal motor vehicles for transportation, pedestrian and motor vehicle collisions is one of the leading causes of unintentional-injury related morbidity and mortality among children.2

In the United States, children aged 0-15 years experience the highest rate of non-fatal injuries.3 Children ≤ 15 years of age account for 30% of all pedestrian injuries and 8% of all pedestrian deaths.3 Sixty-three percent of these pediatric deaths involving children < 14 years of age were males.3

Timely arrival at a trauma center is critical.4 In the United States, death rates prior to arriving at the hospital occur 21% of the time. Increased transit time to a designated trauma center has been determined to be the critical factor.5 The greater the distance between the place of collision and a trauma center, the worse the outcome for the pedestrian.

In pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions involving children, the most common injuries are traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and musculoskeletal injuries, followed by chest and abdominal injuries.3 With musculoskeletal involvement, injuries to the upper and lower legs and knees are the most frequent, which can lead to long-term disabilities. However, injuries to the head are generally more life threatening.3

The injuries sustained by children and adults from pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions often require a multi-disciplinary approach. This includes medical care, rehabilitation (i.e., physical therapy and occupation therapy), psychological support, and ongoing monitoring and follow-up, depending on the individual’s unique needs and severity of their injuries. Of interest in this case report is the addition of chiropractic care for a patient undergoing long-term medical care and rehabilitation. The chiropractic perspective, with a traditional emphasis on the importance of structure and function, remains largely unexplored in the care of pedestrians involved in motor vehicle collisions. To address this deficit, we describe the chiropractic care of a woman suffering from injuries sustained from a pedestrian-motor vehicle collision 22 years prior.

Case Report

A 26-yr-old woman was referred by her co-worker for chiropractic evaluation and possible care with a chief complaint of left leg dysfunction resulting in a gait impairment along with urinary incontinence.

At the time of clinical presentation, the woman was a patient at Stanford Hospital’s Orthopedic Department (Palo Alto, CA) where the current physician to her case indicated that she had a condition called pelvic obliquity. At her initial chiropractic consultation, she was observed as she walked into the clinic with an obvious gait impairment that was best described as a “swing gait” of the left leg. As she stepped forward with her left leg, she would swing her leg out laterally and anteriorly. Upon closer inspectionshe was wearing a left leg brace that ran from the back of her knee to her foot. The brace was L-shaped with a 1½-inch (37.5mm) shoe lift.

Her past history showed that at age 4, she was running across a street when she was struck by a motor vehicle. She recalled having been dragged approximately 1 block with the car tires rolling over her legs and lower body. Not surprisingly, she suffered multiple head injuries and was comatose for 8 days. She received care on an outpatient basis at a local Children’s Hospital in the physical therapy department following her initial hospitalization. At 18 years of age, she was transferred to the Stanford Hospital and treated as an adult outpatient for her physical impairments. She related that her lower extremity problems were attributed to an “upper motor neuron lesion” and that “brain injury” was a term that she has basically dealt with her whole life. She was told by many of her medical caregivers that she should expect to have impairments for the rest of her life as a result of her “brain injury.” According to the patient, no one had actually evaluated her physical condition as an adult, until an orthopedist evaluated her and found that her pelvic girdle was not of “normal alignment” and hence the diagnosis of pelvic obliquity. She was motivated towards chiropractic care to see if chiropractic could help with her left leg dysfunction and improve her gait, which the patient described as a “foot drop.”

In addition to her mobility difficultiesshe admitted to suffering from bladder dysfunction. She characterized this as needing to urinate every 12-15 minutes (day and night), never having a full sensation of relief after voiding and always having a sense of urgency. As a result, in order to avoid a life in diapers, her social and travel activities were severely restricted since she could not venture into places where a washroom facility was too far away. She denied currently experiencing pain in her lower extremities or in the pelvic girdle or low back.

On physical examination, she demonstrated contact dermatitis of the lower left leg due to the leg brace. She related that in order to strap her leg and foot into the brace, she would have to sit and lean forward while forcing her foot into a neutral position prior to insertion into the brace since her foot was in a fixed and rigid plantar flexed position. Also, without the brace, her left knee was observed to be naturally fixed in a 10°-15° flexed position. As a consequence, she had an obvious leg-length inequality. Inspection of the left knee revealed joint derangement with her tibial plateau misaligned underneath the femoral condyles. Her femoral condyles were significantly anteriorly displaced relative to the tibial plateaus. On digital palpation of her left leg, muscle rigidity was seen in the left gastrocnemius muscle. The left Achilles tendon was noticeably shorter consistent with the rigid and fixed plantar flexion of the left foot. The left calcaneal talar joint was also misaligned upon palpation. The left talus was translated significantly from underneath the mortis joint so that her left foot without the brace was in forced plantar flexion. Additionally, her left hallux was in a permanent state of dorsiflexion when compared to the right. She demonstrated a positive Babinski sign on the left side. She denied having left leg pain but admitted to paresthesia or a “butterfly feeling of the left thigh.” On sensory testing, she described a reduced sensation in the left leg relative to the right leg. She could feel and describe sensations on the left leg with touch and pinching, but the sensations were characterized as if “the volume had been turned down.” Myotomal testing was not performed due to the physical state of her left leg. Romberg’s test was positive, as were Trendelenburg’s and Heel and Toe Walk testing. Deep tendon reflexes (Patellar and Achilles) were unremarkable. There was a noticeable difference in girth of the left thigh and leg relative to the right leg due to disuse atrophy.

With palpation of the lumbopelvic region, her left groin area, left hip and thigh region were extremely hard and rigid. The entire medial aspect of the right pubic bone was misaligned anteriorly and could be more accurately described as a luxation of the pubic symphysis. More specifically, there was posterior translation (-Z) of the left innominate. The patient’s left innominate was palpated to be subluxated as a posterior-inferior (PI) ilium (i.e., -X; -θY). In addition, a leg-length inequality was noticeable while the patient was in the prone position. The left leg was relatively shorter compared to the right leg. As the patient’s heels were positioned towards the buttocks so that the knees were flexed at 90°, the flat of the left foot was noticeably more elevated relative to the flat of the right foot suggesting PI subluxation on the left side. Her right innominate was subluxated (relative to the left innominate bone) in an anterior-superior (AS) (+X; +qY) direction. As previously noted, the patient’s left knee was in permanent 10°-15° flexion with the patient incapable of fully extending the knee but could achieve full knee flexion. Her left ankle was in a fixed plantar flexed position with little motion. She related that on Babinski reflex testing of her left foot, her left hallux would dorsiflex a “little bit more.” The patient’s left heel was palpated to be posteriorly displaced. Interestingly, upon tractioning her left heel anteriorly to correct its position, her ipsilateral big toe (hallux) would plantar flex.

Based on the history and physical examination findings, we radiographed her lumbo-pelvic region (see Figure 1). Although a number of techniques are available to measure the radiographic parameters for pelvic obliquity (i.e., the Osebold, O’Brien, Allen and Ferguson, Lindseth, and Maloney techniques),6 pelvic obliquity was most apparent on her radiological AP pelvic view. Note the unleveled position of the inferior pubic rami and femur heads with respect to the horizontal, the unequal size of the obturator foramen, and the obvious luxation of the pubic symphysis. The ischial spine was also visible on the right but not on the left with asymmetry on the lateral aspects of the pelvic inlet (i.e., the arcuate line on the inner surface of the ilium, and the pectineal line on the superior pubic ramus).

Chiropractic Care

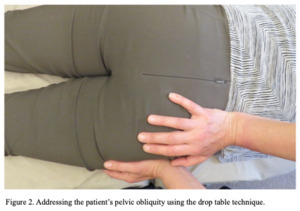

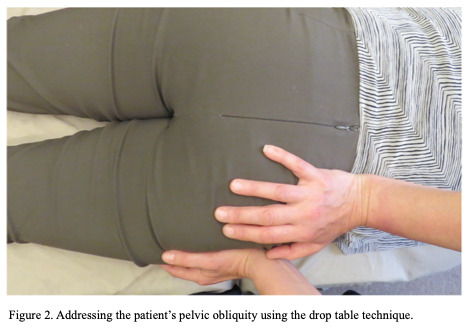

On the first visit, drop table technique7 was utilized to re-align the pelvis. Her pelvic subluxation was such that she had a PI ilium (-θY) of the left innominate, concomitant with a posterior (-Z) displacement pattern of the left pubic symphysis relative to the contralateral side.

She was positioned prone on the drop table with a wedge-shaped foam support placed underneath the patient’s right innominate (see Figure 2). We contacted her left pelvis with both hands as shown in Figure 2. A thrust was applied with vectors posterior to anterior and superior to inferior to activate/release the drop piece. This was performed multiple times (i.e., 10 times) until palpation findings indicated that the patient’s pubic symphysis was aligned. The patient indicated no pain or discomfort during this procedure.

The drop table technique was also applied to realign her left tibia with the femur and to realign the left talus with the left tibial/fibular joint. She was placed in a supine position and a Thuli speeder board (Thuli Tables. Dodgeville, WI, 1982) was used for this purpose along with a 4-inch foam roll placed underneath her left tibia (see Figure 3). With a contact point superior to the left patella, a thrust was applied with vectors anterior to posterior to release the drop piece. This procedure was gently performed approximately twenty times. Based on palpation, her left tibia aligned with the femur. Again, the patient indicated as experiencing no pain nor was there any cavitation during the procedure. Following the adjustments to the pelvis and left knee, her left gastrocnemius muscle was palpated as a reducing in her previously noted muscle tension. and she was able to fully extend her knee.

To address the ankle subluxation, she was positioned as shown in Figure 4. With the patient seated and her left knee in flexion, her left heel rested on a speeder board and placed over a drop piece. Her left ankle was placed in a neutral position and a force was applied with a line of drive of superior to inferior and anterior to posterior. The force applied was sufficient to release the drop piece but gentle enough so as to cause no pain or discomfort to the patient. This was repeated 12 times until the ankle subluxation findings were reduced as much as possible based on palpation. Following the adjustments to the left ankle, she was able to plantarflex and dorsiflex the ankle. In comparison, she had negligible range of motion at the left ankle joint prior to the extremity adjustments. As previously describedher left foot was in a rigid plantar flexed position without the ability to perform dorsiflexion. As a result, the patient would have to sit and lean forward while forcing her foot into a neutral position in order to insert on her left foot and leg into her leg brace. Passive eversion and inversion of the patient’s ankle was minimal.

To evaluate her response to the care provided, she was instructed to walk a few steps. The patient’s gait changed dramatically, particularly with an improvement in the left leg swinging out laterally and her independence from the use of the leg brace. Upon noticing the dramatic changes in her ability to walk, the patient became emotional and began to cry.

Outcomes of Chiropractic Care

Following the initial office visit, she no longer needed to use her brace. She was able to walk with some flexion of the left hip, flexion/extension of the left knee, and some dorsiflexion of the left ankle and foot that eliminated entirely the need for her brace. Additionally, she indicated a dramatic improvement in her quality of life as a result of an improvement in her ambulation but also freedom from the need to have shoes that required fitting to accommodate the leg brace as well as a shoe lift.

Two weeks after the initiation of care, she reported that her urinary problems had improved. Her feelings of urinary urgency, never fully voiding, and needing to urinate every 10-15 minutes had disappeared. She now needed to go to the bathroom only every 2-3 hours. SHe was initially scheduled for chiropractic care 1-2 times a week for 2 months. However, her visits became sporadic, often missing appointments or re-scheduling.

At 3 years follow-up, she continued to be a chiropractic patient. However, her history of missed appointments continued, and no consistent amount of care was ever established. According to the attending chiropractor, she continued to have a pelvic imbalance with altered gait. Her “swing gait” had disappeared along with her dependence on the leg brace but she still could not fully extend her left knee and, occasionally, she dragged her left foot slightly on walking. The chiropractor noted that after each visit, her left leg muscles were more relaxed, and her gait improved. At the time of writing, the patient continued to receive chiropractic adjustments to her pelvis, her left knee, and left talus along with stretching exercises to the Achilles tendon, the left psoas muscle, and the left hallux tendon.

Despite attempts to facilitate the patient towards regularly scheduled chiropractic care, the patient was non-compliant with her scheduled visits.

Discussion

This case report presented the chiropractic care of a 26-year-old woman with long-standing musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal complaints sustained from a pedestrian-motor vehicle collision 22 years prior. SHe was cared for with high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) type spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) with the use of a drop table. The result was improvement in her ability to walk without the use of a leg brace and resolution of her complaints of urinary urgency, nocturia, and the need for frequent urination. The results of this case report are therefore ripe for discussion providing the chiropractic perspective with respect to the patient’s pelvic obliquity, lower extremity/locomotor dysfunction, and bladder dysfunction.

Pelvic Obliquity

Pelvic obliquity has been described as the failure of the pelvis to lie in a perfectly horizontal position in the frontal plane.8 However, as raised by Dobousset,9 this is not a realistic description as the pelvis is a 3-dimensional structure consisting of the sacrum and coccyx, and 2 innominate bones (i.e., pubis, ischium, and ilium). There are 4 joints in the pelvis - the sacrococcygeal joint, 2 sacroiliac joints, and 1 symphysis pubis anteriorly.10 Within the pelvis are housed blood vessels, nerves, urogenital organs, and the rectum. In addition to trauma, the causes of pelvic obliquity are many and include a number of conditions leading to neuromuscular dysfunction in the pelvis or trunk, scoliosis, conditions affecting the acetabulofemoral joint, gait abnormalities, and leg length discrepancies. Examples of clinical conditions leading to pelvic obliquity include Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy,11 myelomeningocele,12 cerebral palsy,13 polio,14 stroke leading to motor impairment,15 and from a chiropractic perspective, subluxations of the pelvis and lower extremities. The consequences of pelvic obliquity involve distorted growth and structural changes in both osseous and soft tissue elements of the spine and pelvis, leading to further dysfunction.

For our patient, concomitant with her pelvic obliquity was the finding of a misaligned pubic symphysis.16 As demonstrated in the anterior to posterior view of the patient’s radiographs (see Figure 1), the patient’s symphysis pubis was severely misaligned or subluxated along with subluxations of the sacroiliac joints. Furthermore, according to the attending chiropractor, the radiographs did not fully reflect the patient’s clinical presentation of pelvic obliquity or misalignment. Palpation findings of the pubic symphysis revealed significant subluxations as described in the case narrative. According to Ruch,16 subluxation patterns of the pubic symphysis involve shearing patterns in the antero-posterior (i.e., ±X) and superior-inferior (i.e., ±Z) direction. The patient described in this case report had a right pubic symphysis misalignment that had translated anteriorly (i.e., +X) concomitant with a AS (+θY) subluxation. This was addressed with chiropractic adjustments using the drop table technique.

The preferred term to describe the patient’s pubic symphysis in this case report is pubic symphysis diastasis (PSD) based on the radiographic diagnosis of an abnormal symphyseal separation of ≥10mm (see Figure 1). Due to the similarities in clinical presentation, PSD has been associated synonymously with osteitis pubis or symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD). Osteitis pubis is a non-inflammatory process, which radiographically demonstrates irregularity in the pubic symphysis articulation, erosion, sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. Symphyseal joint laxity or disruption is present with widening of the joint space of ≥7 mm and malalignment of the upper margins of the superior pubic rami of more than 2 mm on radiological flamingo views of the pelvis (i.e., three radiological antero-posterior views of the pelvis with the patient in neutral stance, left foot raised and right foot raised).17–19

The classic features of pubic symphysis diastasis include pain over the pubic symphysis, occasional symphyseal clicking, and locomotor difficulties. In addition, low back pain may occasionally be a complaint.20 The locomotor difficulties in the patient with SPD are usually attributed to the pain experienced by the patient as weight distribution is shifted from one side to the other, as in walking up a flight of stairs. Radiographically, a normal upper limit of interpubic gap is usually 10mm, but in symptomatic women with SPD the median gap could be as much as 20mm.21 Our patient fulfilled the radiographic criteria for PSD and SPD. However, unlike SPD, the patient demonstrated only 1 of the common clinical findings - that of locomotor dysfunction. It may also be argued that her locomotor dysfunction was attributable to injuries in the left lower extremities (i.e., knee and ankle joint derangement) sustained from the pedestrian-motor vehicle collision at 4 years of age rather than from SPD or PSD alone. According to Chawla et al.,22 the magnitude of separation does not correlate well with the severity of symptoms with treatment modalities ranging from conservative care involving analgesics, pelvic binders, physiotherapy modalities, and chiropractic care, to more invasive interventions such as external fixation or open reduction and internal fixation.

Interestingly, Cooperstein et al.23 described the management of a 24-year-old nulliparous woman with overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome secondary to SPD. Similar to the patient presented in this case report, their 24-year-old patient presented with urinary frequency, urgency, and/or urge incontinence absent urinary tract infection. Radiographic examination taken 2 years prior of the patient by Cooperstein et al. was interpreted as normal. The patient presented in this case report had a diastasis or notable separation of the pubic symphysis as visualized on anteroposterior view of the lumbopelvic region(see Figure 1). Cooperstein et al.23 described the care of the patient as consisting of chiropractic adjustments to the pelvis to address the pubic symphysis subluxation along with exercise. Adjustments to the pelvis were described as the patient in a side-posture position with the right side up and ipsilateral to the side of the cephalad pubic ramus. The chiropractor stood behind the patient and faced inferiorly, made a pisiform contact with the lateral aspect of the iliac crest and delivered a series of 3 high-velocity low-amplitude thrusts from superior to inferior, releasing the pelvic section of the drop table. The patient attended a total of 6 visits over a 4-week period. In week 4, the patient’s final treatment was associated with normal symphysis pubis alignment and report of 7 hours of uninterrupted sleep whereas previously the patient reported less hours (≤4 hours) of consecutive sleep. At 1-year follow-up, the patient completed an Overactive Bladder Questionnaire24 that assessed patient’s daytime frequency, sudden urge, uncomfortable urge, volume, strength of desire to void, urine loss with stressors, waking up with urge, and nocturia. The patient’s score was reported as 2/20 compared with a baseline 9/20. The higher the score the more severe the OAB syndrome.

Lower Extremity Complaints

Our patient had locomotor difficulties and used a brace on her left leg, which was determined as needed for her to walk by her medical and physiotherapy providers. Keep in mind that her locomotor dysfunction (i.e., a lateral swing gait of the left leg) was not associated with any pain at the pubic symphysis, at the lumbar spine, or in the left knee and left ankle. This lack of pain complaint may be clinically unexpected for some. However, given the patient’s TBI and the wide array of possible neurological deficits she may have sustained, the patient’s lack of pain sensation despite her long-standing musculoskeletal dysfunctions cannot be attributed solely to the body’s ability to adapt to the internal and external stressors placed upon it. Conversely, her lack of pain sensation cannot solely be attributed to the TBI she sustained. However, there are indicators that this may be the more cogent explanation since sensory testing revealed the patient had reduced sensation (i.e., as if the volume had been turned down) in the left leg relative to the right leg. This would allude to a possible sensory deficit in pain sensation.

As described in the case report narrative, she had a considerable degree of joint derangement/extra-spinal subluxation in these regions over a period of 22 years. It has been estimated that 20-50 percent of pedestrians involved in pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions develop chronic pain.25 The risk factors for chronic pain in individuals involved in pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions are older age, the severity of their injuries, and the presence of pre-existing conditions. Even those with minor injuries may also experience chronic pain, particularly when psychological factors (i.e., post-traumatic stress disorder) are present.26

Chiropractors have long held the fundamental concept that structure dictates function and vice versa. The results of chiropractic care in the case presented were dramatic. The attending chiropractor attempted to achieve mechanical re-alignment through adjustments of the pelvis, left knee, and left ankle. This not only resulted in improved ambulation for the patient but also an improvement in a “seemingly unrelated problem,” that of bladder dysfunction. Note that the adjustments performed on the patient were characterized as HVLA thrusts with the assist of a drop table. The adjustments may also be described as focused or specific to a particular articulation and graded. Graded in the sense that the initial thrusts were “very light” with greater force applied with subsequent thrusts. The amount of force applied was based on the patient’s favorable response by indicating no pain to the HVLA thrusts.

The effects of the chiropractic adjustments to the patient’s left knee and left ankle is consistent with the response of articulations to spinal adjustments or SMT as per Shekelle.27 These include the relaxation of hypertonic muscle, the disruption of articular or periarticular adhesions, and unbuckling of motion segments that have undergone disproportionate displacements. For an excellent discussion on these aspects of SMT on the spine, we recommend the article by Evans.28 As noted by Hoskins et al.29; despite chiropractic’s focus on the spine in the last 25 years with well-conducted research on low back pain, neck pain and headache, there also exists the care of conditions of the extremities that has been around since the early part of chiropractic’s inception.30,31 An examination of the reviews of the literature by Hoskins et al.29 and Brantingham et al.32,33 revealed that conditions involving the knee mostly involved knee pain from osteoarthritis or patellofemoral pain syndrome. Similarly for the ankle, ankle sprain and ankle equinus were the most common conditions addressed in the published studies. Insofar as we are aware, the effects of chiropractic care on the lower extremities involving the knee and ankle as presented in this case report is the first of its kind.

Non-MSK Complaint

From a chiropractic clinical perspective, this case demonstrates what is commonly reported in chiropractic practice. A patient enters chiropractic care for a musculoskeletal problem and concomitant with a successful outcome in the patient’s musculoskeletal symptoms, the patient also reports improvement in a comorbidity that was not intentionally addressed by the chiropractor. In this case, the patient’s bladder dysfunction, never having improved through long-term allopathic approaches (i.e., orthopedic, physical therapy), resolved with dramatic improvement in the patient’s overall quality of life. The constellation of symptoms (i.e., urinary urgency, the need to urinate every 10-15 minutes, nocturia, and urge incontinence) described by the patient in this case report is consistent with the diagnosis of OAB.34 Severe pelvic trauma can result in persistent urogenital problems due to damage to the pelvic floor, prolapse, or neurological injury.35,36 Structural alterations in rotation, for example due to pelvic obliquity, can cause symptoms due to space constraints. For example, urinary disorders can occur due to irritation of the bladder as a result of displacement of the superior pubic ramus.37 This is consistent with the attending clinician’s opinion that the left pubic bone, being significantly posteriorly subluxated, caused a physical compression/irritation of the bladder and thus bladder dysfunction.

The etiology of OAB is multifactorial and still somewhat enigmatic. In the case report by Cooperstein et al.,23 the authors suspected their patient’s nocturia was due to a urine storage disorder, while in the case here, the patient’s symptoms may be a result of trauma to the spine and pelvis, the resulting structural alteration to the pelvis, and neurological consequences. However, we believe that similar mechanisms may be at play in both patients involving somato-vesical reflex (i.e., reflex involving the bladder and the somatic or voluntary nervous system). We encourage the reader to read Cooperstein et al.'s23 excellent dissertation on somato-vesical reflex. As reviewed by Qin et al.,38 micturition is controlled by a complex neural network involving the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and somatic pathways. Relaxation of the urethra occurs through the parasympathetic (pelvic) nerves via activation of muscarinic-3 receptors while sympathetic (hypogastric) nerves enables inhibition through β-3-adrenergic receptors. Pudendal nerves originating from S2 to S4 motor neurons in the Onuf’s nucleus allows for the excitation of the external urethral sphincter. The storage of urine is primarily maintained by reflex effects in the spinal cord involving the hypogastric and pudendal nerves innervating the urethra along with the pontine storage center located closely to the pontine micturition center (PMC), hypothalamus, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and frontal cortex. The PMC has been postulated to initiate the micturition cycle by receiving afferent input from the lumbosacral spinal cord due to bladder distention as well as the prefrontal cortex, which allows for the social acceptability of voiding. The prefrontal cortex controls executive functions, such as thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making. It also helps regulate emotions, motivation, and social interactions. Other structures such as the periaqueductal gray (PAG), insula, and anterior cingulate gyrus also act to provide awareness of visceral sensations. Furthermore, the PAG is considered to mediate the function of storage to voiding of urine and regulated by higher brain regions such as the hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex. Therefore, lesions of the central or peripheral nervous system from trauma (and the resulting pelvic obliquity) as in the case reported could possibly disrupt the neurological control of micturition, resulting in the symptoms of OAB - voiding urgency, frequency, incontinence, and nocturia. We note that contained within the pelvis and innervating the pubic symphysis are the pudendal nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, the iliohypogastric nerve, and ilioinguinal nerve. Re-alignment of subluxated structures may have the potential effect of altering or reversing the pathological somatosomatic and somatovisceral reflexes leading to the symptoms of OAB.

As mentioned previously, the most common injuries in pedestrian-motor vehicle collisions involve traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) and musculoskeletal injuries.3 Although a study on health care utilization following hospitalization for a TBI showed that a significant proportion of TBI sufferers were super-utilizers (i.e., having three or more emergency department visits or inpatient encounters or more than 26 outpatient visits during the year),39 TBI sufferers also face barriers and challenges to receiving healthcare services. To examine patient and caregiver experiences of health services for individuals with moderate to severe TBI in Indiana, Eliacin et al.40 performed semi-structured interviews of individuals with TBI. Three themes emerged from their analysis of the interviews. These were: 1) inadequate access to health services, 2) unavailability of specialized, age-appropriate, and long-term health services, and 3) transportation barriers to health services that limit access to care and amplify rural health disparities for patients. To what extent these apply to accessing chiropractic care deserves further examination. However, the patient presented in this case report attended her chiropractic care appointments sporadically, despite the cost of her chiropractic visits being discounted. Challenges to attending her scheduled chiropractic visits may be attributed to cognitive impairment, transportation issues, and lack of caregiver support to navigate appointments for chiropractic care. These deserve further investigation to examine the role of chiropractic in the care of patients with TBI and musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal injuries.

Limitations of case reports

Based on the research paradigm of post-positivism, case reports have inherent limitations such as the presence of potential bias, the inability to make cause and effect inferences, and their lack of generalizability. Nonetheless, case reports are a valuable means to describe the clinical encounter and contribute to the advancement of clinical practice and patient care. In this regard, we ascribe to the research paradigm of constructivism to guide the interpretation of case reports as in the case presented.

Constructivism as a research paradigm is based on the premise that there are multiple realities that are constructed by individuals based on their experiences and social interactions with others. As in the case reported, the clinician-scientist actively engaged with his patient/research participant to co-construct knowledge based on the subjective experiences of the patient and the clinical experience/expertise of the attending chiropractor. This is a means by which we understand a patient’s subjective meanings and interpretations with their care rather than seeking a single, objective truth. In the case reported, we expect others in healthcare, particularly other chiropractors, to confirm, challenge, or provide alternative explanations to the observations described in this case report. Towards such efforts, the chiropractic profession may further develop the critical skills necessary to create evidence-based knowledge for its implementation in clinical practice.41

Conclusion

This case report highlights the chiropractic structuralist point of view wherein mechanical alignment of misaligned osseous structures (i.e., chiropractic subluxation) results in the restoration of musculoskeletal and visceral function.

Funding

This study was funded by Postura, Oakland, CA and the International Chiropractic Pediatric Association, Media, PA.

Informed consent

Informed consent forms have been signed and submitted.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial issues or conflicts with this article.