Introduction

Documentation is considered a cornerstone process indicator of quality patient care.1 It functions to safeguard both patients and healthcare providers alike by archiving pertinent components of clinical encounters.2 Standard healthcare documentation includes a history of present illness, physical examination, vital signs, test results, treatments, procedures, and/or plans for ongoing care. Health information is captured and recorded in a patient’s electronic health record (EHR) through a combination of free text entry and structured data fields (e.g. International Classification of Diseases-10).

Chart audits are a regular practice of healthcare systems to ensure documentation integrity and compliance.3 Comprehensive electronic health records also provide an opportunity for researchers to characterize documentation practices among providers via chart reviews.

Previous investigators have examined the frequency of recommended history and examination elements performed by health care professionals. An observational cohort study of patients presenting with acute musculoskeletal pain to a large, academic medical center found that providers used selected history and examination elements 43 ± 16% and 28 ± 17% of the time, respectively.4 A retrospective medical record review used to assess compliance with low back pain (LBP) care indicators in the general Australian population revealed that patients presenting with LBP had their medical history documented at presentation 82% of the time by general practitioners (GPs) and 98% by allied health professionals. Additionally, this study found that 22% of GPs and 75% of allied health professionals documented performing a neurological exam in LBP patients.5

Little is known about how frequently chiropractors perform recommended history and examination procedures. Self-reported data from a provider survey of US chiropractors (n= 3,876) shows patient assessment is done daily in clinical practice, including problem-focused case history (73%), observation (57%), and a focused orthopedic/neurologic examination (51%).6 In a survey of Veterans Health Administration (VA) chiropractors (n=118), over 95% of respondents self-reported performing patient history and examination elements, including observation, palpation, range of motion, orthopedic and neurological testing, several times per day/week.7 In a cross-sectional analysis of VA chiropractic clinics assessing patients with LBP (n=592), it was found that medical history was documented in 448 (76%), physical examination in 454 (77%), and neurologic examination in 371 (63%) notes.8

As part of the process of ongoing professional practice evaluation, VA clinicians undergo routine peer chart review, which is guided by internally developed clinical indicators. This peer evaluation of care includes assessment of history and examination at the individual level, however, to date there has been no investigation of the use of history and examination procedural elements by VA chiropractors at the national level. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the frequency with which key history and examination elements were documented at initial chiropractic visits within the VA nationally.

Methods

This study is part of a broader VA quality improvement project which has been described elsewhere.9 This work has been determined to be a quality improvement project by the VA Connecticut Healthcare System’s Research office and therefore did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Study Design and Data Collection

This project was a cross-sectional analysis of VA national electronic health record (EHR) data. Using structured queries of the VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW),10 we identified a random sample of 1,000 on-station chiropractic consultation visits in fiscal year 2018 (10/01/2017-09/30/2018). Cases were limited to patients without visits to a VA chiropractic clinic within the previous year. Data were provided by the Office of Analytics and Performance Integration under the Office of Quality, Safety, and Value, Department of Veterans Affairs. Key structured data including patient demographics and diagnosis codes were extracted from the CDW. A manual chart review was conducted by an independent external peer review contractor, Quality Insights, Inc. (Charleston, West Virginia, USA) to abstract clinical characteristics documented in the provider’s free text using a standardized chart abstraction methodology.8 Characteristics abstracted included history, examination, musculoskeletal diagnoses, treatments, and case management. For this specific analysis, we focused on key history and examination elements, and a subset of diagnostic groupings. The operational definitions guiding chart abstraction of these data elements are presented in Figure 1. Diagnoses were not mutually exclusive (e.g. participants could have both a low-back and neck pain diagnosis).

Analysis

History and examination outcomes were summarized for demographic and clinical characteristics as medians and means with SDs for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Bivariate relationships between categorical variables were assessed using chi-squared tests. Multivariate linear regression (significance at α = 0.05) was used to examine the association between the number of history elements and number of examination elements present in visit documentation, adjusted for covariates. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine predictors of visits containing documentation of ≥4 history and ≥4 examination elements, separately. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (v2408, Redmond, WA)) and Stata (v18, College Station, TX).11,12

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The mean age of participants was 52.5 (SD 15.6) with most participants being White (74.1%), non-Hispanic (91.3%) and male (82.0%). The most common free text diagnoses were any low back pain (75.6%) and any neck pain (39.9%), with general low back pain (51.6%) and general neck pain (35.9%) being present in documentation more frequently than low back pain with radiculopathy (23.9%) and neck pain with radiculopathy (4.0%). The most common number of free text diagnoses documented were 1 (44.8%) and 2 (30.7%). No free text diagnosis was documented in 2.7% of visits (Table 1). Of the visits containing no free text diagnosis, 100% of these contained a diagnostic (ICD-10) code.

History and Examination Elements

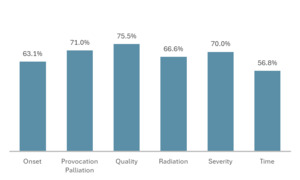

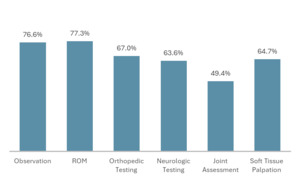

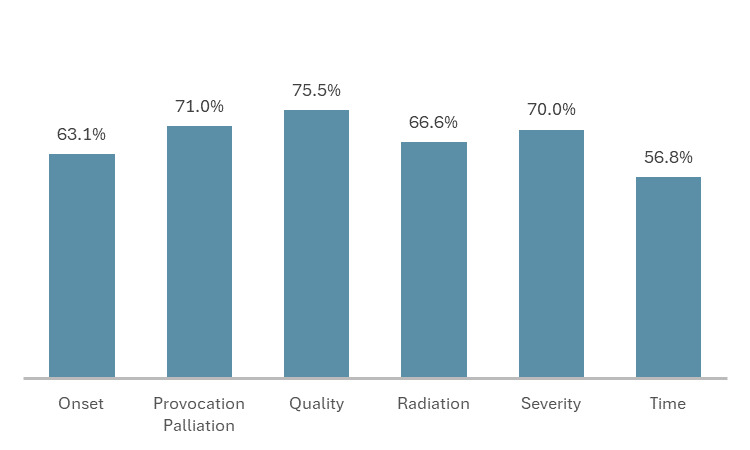

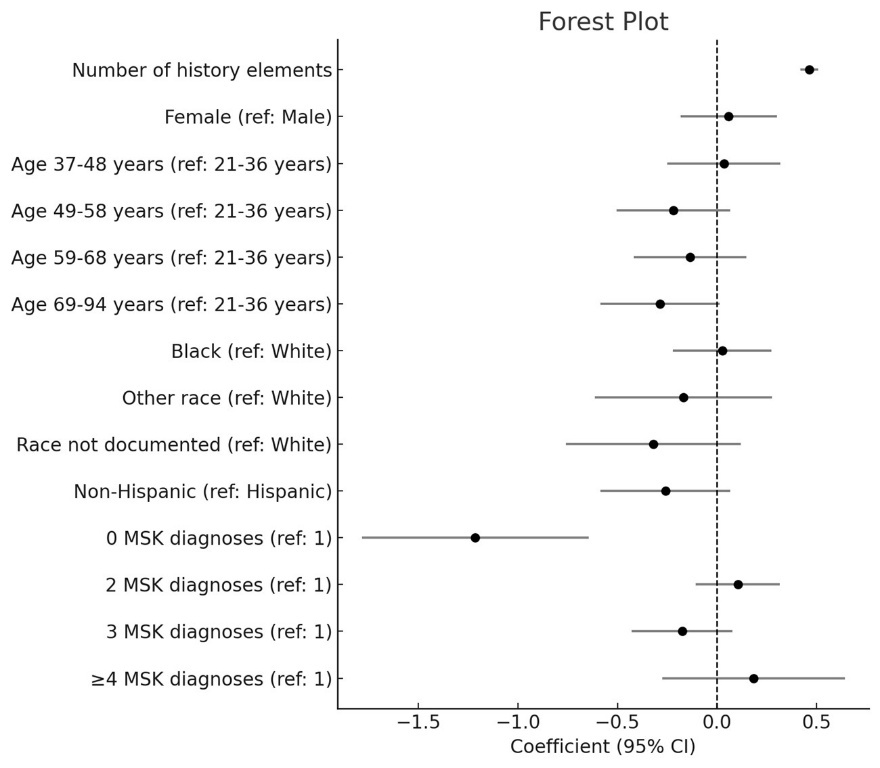

The most frequently documented history elements were quality (75.5%), provocation and palliation (71.0%), and severity (70.0%) (Figure 2). The most frequently documented examination elements were range of motion (ROM) (77.3%), observation (76.6%), and orthopedic testing (67.0%) (Figure 3). Joint assessment was documented least frequently (49.4%). In linear regression adjusting for sociodemographic factors, the number of history elements (regression coefficient: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.42, 0.51) was significantly positively associated with the number of examination elements, while the lack of a musculoskeletal diagnosis (regression coefficient: -1.21, 95 % CI: -1.78, -0.65) was significantly negatively associated with the number of examination elements (Table 2). No other associations were significant. The regression coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals are graphically summarized in Figure 4.

Visits Containing Documentation of ≥4 History and Examination Elements

In total, 639 (65.3%) visits contained ≥4 documented history elements, 657 (67.2%) had ≥4 documented examination elements, and 523 (53.5%) visits contained both. Visits containing ≥4 examination elements were significantly more likely to contain ≥4 history elements (adjusted OR: 7.15, 95% CI: 5.26, 9.72). Similarly, visits containing ≥4 history elements were more likely to contain ≥4 examination elements (adjusted OR: 7.13, 95% CI: 5.25, 9.69). Visits without an MSK diagnosis were significantly less likely to contain ≥4 examination elements (adjusted OR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.58). No other variables were significantly associated with visits containing ≥4 history or ≥4 examination elements (Table 3).

Discussion

This work appears to be the first published assessment of key history and examination elements documented at initial patient visits by a group of US chiropractors. Prior studies have highlighted the crucial role of adhering to clinical practice guidelines in producing optimal patient outcomes. Our study provides a benchmark of the evaluation elements performed at initial visits within VA chiropractic clinics, which provides context for ongoing quality assessment.

The demographics and clinical characteristics of patients in our study are similar to those reported in other VA chiropractic studies. The demographics of patients in our study (74.1% White, 91.3% non-Hispanic, 82.0 % males) closely match previously reported demographics of VA chiropractic users (61.8% White, 87.9% non-Hispanic, 84.4% males).13 The demographics seen in our study and other studies of VA chiropractic clinics differ from the demographics of chiropractic care users in the U.S. general population, where women make up a larger percentage (55%) of users.6 Low back and neck pain without radiculopathy have previously been reported to be the most common pain presentations to VA chiropractic clinics.7,14 Similarly, our study found that while general low back and neck pain are most common, low back and neck pain without radiculopathy were the most common subgroups. The conditions seen by the general U.S. chiropractor are consistent with those seen within VA chiropractic clinics with low back and neck pain being most common.15

There was a strong bidirectional association between documentation of history and examination elements in analyses. We suspect these findings could reflect clinical thoroughness, documentation habits, or both. Additionally, our study found that there was no documented free text diagnosis in 2.7% of visit notes. However, after further investigation, we found that each of these visit notes contained a diagnostic (ICD-10) code. This highlights the potential for incongruence between free text documentation and structured data fields (e.g., diagnostic and procedural codes). This incongruence may not necessarily reflect the quality of care delivered but is an important consideration in studies conducting analyses of EHR data.

Our findings align with and expand on previous research that examined elements of history-taking and examination procedures in the management of musculoskeletal pain conditions. In a 2021 cross-sectional survey evaluating initial diagnostic workup of new patients in VA chiropractic clinics, the great majority of respondents self-reported using clinical evaluation methods such as history-taking, orthopedic and neurologic examination, joint and soft tissue palpation, and range of motion assessment.7 This is congruent with our current finding that documentation of orthopedic and neurological examination, soft tissue palpation, and ROM occurred approximately two-thirds of the time or more, with joint palpation occurring nearly half of the time. While participants of the 2021 provider survey self-reported performing patient history-taking procedures several times per day/week, our present analysis found documentation of key history elements varied between 57-76%. It is important to note, however, that our study examined individual elements of patient history-taking while the previous study assessed patient history-taking as a broad category.

Limitations

This study used manual chart review which is subject to human error, although we minimized this through use of a standardized abstraction tool and reviewer training process. We assessed EHR documentation, which may provide only a partial view of actual clinical practice and may not accurately depict the services chiropractors provided during visits. Additionally, this work is an assessment of VA chiropractic clinics and may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems and/or private practice.

Future Studies

To better understand history and examination elements used during a course of care, future work should assess initial visits plus a series of follow-up treatment visits. Additionally, since data obtained by chart review are based on the accuracy of clinical documentation, it may be more valuable for future work to measure the procedures directly occurring in chiropractic visits. Such work could include real-time direct observation, assessment of video recordings, and/or the use of ambient artificial intelligence (AI). Patient privacy and information security considerations impact the feasibility of all three methods, yet evidence suggests that the use of ambient AI has the potential to significantly improve documentation quality while saving time during consultations without significant reduction in patient-facing time.16

Conclusion

We present an initial investigation of documentation of history and examination elements in VA chiropractic consultation visits. These results may inform future research and quality improvement efforts.