Introduction

Pediatric chiropractic care has experienced significant growth internationally, with an increasing number of children receiving chiropractic care for various health conditions.1–4 Despite this growth, comprehensive data characterizing pediatric chiropractic practice patterns remain limited, creating challenges for evidence-based clinical decision making, educational curriculum development, and healthcare policy formulation.

Recent updates to the 2009 and 20165,6 clinical practice guidelines have established evidence-based recommendations for pediatric chiropractic care, emphasizing the importance of specialized training and age-appropriate treatment modifications.1,4 The 2023 consensus-based clinical practice guidelines developed through a modified Delphi process provide the most current recommendations for pediatric chiropractic practice, and along with the best practices 2022 article4 reflects the contemporary zeitgeist of evolving evidence-based practice and clinical expertise in pediatric chiropractic care.

Systematic reviews of manual therapy for pediatric patients have identified moderate-positive evidence for specific conditions, such as low back pain and pulled elbow, while noting inconclusive (often favorable) evidence for most other conditions.7 Ellwood et al.8 follow suit by showing favorable evidence for manual therapy’s effect on infant crying times. A systematic review aimed at effectiveness of conservative treatment of plagiocephaly9 highlights the fact that manual therapy stands out from other physical therapies as producing “the best results”. These reviews consistently highlight the need for larger, well-designed studies and standardized outcome measures in pediatric populations. A recent pilot RCT investigating the effect of the chiropractic adjustment of vertebral subluxation10 in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has begun the feasibility exploration of this, and called for larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods.11

Safety considerations remain paramount in pediatric chiropractic practice.12–15 Recent research has demonstrated significant differences between active and passive surveillance methods for adverse event detection, with active surveillance identifying adverse events in 8.8% of pediatric visits compared to 0.1% with passive surveillance.16 This substantial underreporting in passive systems has important implications for interpreting safety data from practitioner self-reports.

Parents’ perspectives on pediatric chiropractic care reveal high satisfaction rates, with studies showing that 94% of parents reported positive experiences and 89% indicated they would recommend chiropractic care to other parents.15,17 A secondary analysis of 22 043 responses from parents who had accessed chiropractic care for their children found, through a thematic analysis of open text responses, improvements in general health or well-being (>13 000 references), pain (>7000 references), and sleep (5379 references),18 suggesting strong consumer acceptance and perceived value of pediatric chiropractic services.

The economic aspects of pediatric chiropractic care warrant further investigation. Understanding cost structures, insurance coverage patterns, and accessibility measures is crucial for healthcare policy development and for ensuring equitable access to care. Previous research has shown that chiropractors often implement reduced fee structures for pediatric patients, although comprehensive economic data remains limited.19

Although previous studies have documented variations in chiropractic practice patterns, limited research has examined the economic dimensions of pediatric chiropractic care across different healthcare systems. Understanding international cost variations is useful for healthcare policy development, insurance coverage decisions, and ensuring equitable access to pediatric chiropractic services. The economic landscape of pediatric healthcare varies substantially across countries20,21 due to differences in healthcare system structure, regulatory frameworks, and economic conditions, making international comparative analysis essential for evidence-based policy development. The 4 countries most represented in this study present distinct healthcare system archetypes: Canada’s single-payer universal system, the UK’s government-owned National Health Service, Australia’s mixed public-private model, and the United States’ predominantly private insurance system.

Research priorities in pediatric chiropractic have been identified through consensus processes, highlighting the need for both musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal research.3 These priorities emphasize the importance of understanding current pediatric practice patterns to guide future research directions and clinical practice development.

The present study builds upon previous demographic research on chiropractors who treat children2 by examining the clinical characteristics of pediatric chiropractic practice. This study aimed to provide data on practice patterns, pediatric patient presentations, treatment approaches, outcomes, and economic factors to inform clinical practice, education, and policy development.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional survey study was conducted as part of a larger international investigation of pediatric chiropractic practice. The study protocol was approved by the Anglo European College of Chiropractic Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Survey Development and Distribution

A comprehensive survey instrument was developed based on a literature review, expert consultation, and pilot testing.2 The survey addressed practitioner demographics, training background, patient characteristics, presenting conditions, treatment approaches, perceived outcomes, and practice economics. The demographic profile from this survey of chiropractors who treat children has previously been published.2 The Anglo-European College of Chiropractic Research subcommittee for postgraduate studies gave ethics approval.

Pediatric practice characteristic questions were developed through contemporaneous literature22–25 and expert opinion. The pediatric age group was defined in the first question as those presenting from 1 day to 18 years of age. Age categories were split into 4: less than 3 months of age; 3 to 12 months of age; 1 to 11 years of age; and 12 to 18 years of age. Proportions of pediatric patients seen in each age group were asked and required a total of 100%. Common reasons for presentation were compiled from the relevant literature and expert opinion. Respondents were asked to consider within their pediatric patients, what proportion out of 100 demonstrated worsening, no change and improvement. Regarding adverse events, respondents were asked what percentage of pediatric patients experience mild, moderate, or severe adverse events (defined in the survey in supplement). A broad range of different types of care, noted as used in previous literature, were presented for the respondent to mark all that apply to them. Average number of visits per episode of care were asked, with visits ranging from 1-3, 4-5, 6-15, and 15+. Respondents were asked if they recommended periodic check-ups, and an open text box allowed for an answer to what schedule they check them. Fee information was obtained, with questions regarding fee variance, average fee for children (in local currency) for an initial consultation and a regular visit, and whether any pediatric fees were covered in part or in full by insurance. Referral sources of pediatric patients to the respondent were explored for: under 12 months old; 1 to 11 years; 12 to 18 years old; and how often they referred to another health care practitioner was asked. Time ranges spent by the respondent for first visits and return visits were obtained, with the ranges being: <10 minutes; 11-15 minutes; 16-30 minutes; 31-60 minutes; >60 minutes.

The survey was distributed electronically through 19 professional chiropractic associations on 6 different continents via an introductory email research letter with an embedded link to the survey (both available as supplementary documents). The participants provided their consent by opening the survey through the embedded link, and consent was confirmed via the final sentence stating ‘Clicking on “Next” indicates your consent to participate in this research’. All responses were self-reported. The associations were asked to email their members twice within a 2-week timeframe.

Data Collection

Participants completed the survey online over a 15-day period in July 2010. The Pediatric Practice section was completed by practitioners who reported treating children between 1 day old and 18 years in their practice and consisted of 15 questions. The data collected included the following.

-

Practitioner demographics and training background

-

Patient age distribution and volume

-

Common presenting conditions by age group

-

Treatment techniques and approaches utilized

-

Lifestyle advice provision

-

Perceived treatment outcomes

-

Adverse event occurrence

-

Episode characteristics and costs

-

Insurance coverage and fee structures

-

Referral patterns and healthcare integration

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all the variables. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations. Average visits per episode were calculated per Holt et al26 to determine an average - the midpoint of the range, multiplied by the number of practitioners, sum totalled and divided by the total number of practitioners. Correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationships between practitioner characteristics, practice patterns, and outcomes. Chi-square tests were used for categorical associations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Four countries provided adequate sample size of financial data for robust statistical analysis (USA, UK, Canada and Australia) and represented the major English speaking markets for chiropractic care. Due to a failure of both normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions (Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, both p<0.001), a non-parametric approach was utilised. Given the right skewed distribution and between country variance, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction to control for family-wise error rate. This approach ensures robust and credible results for international cost differences that are not vulnerable to statistical artifacts inherent in parametric analyses of skewed or heteroscedastic healthcare data. All analyses were performed using Python 3.11 statistical software.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 1,142 practitioners from 17 countries completed the Pediatric Practice section of the survey, representing diverse geographic regions. Responses were obtained from Australia, Canada, Germany, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Peru, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Zimbabwe. The largest response groups were from the United States (n=312, 27.3%), Canada (n=298, 26.1%), Australia (n=267, 23.4%), and the United Kingdom (n=265, 23.2%).

Training levels were distributed as follows: no pediatric training (18.3%), undergraduate only (28.6%), post-graduate seminar attendance (31.2%), and post-graduate certificate completion (21.9%).

Patient Demographics and Practice Volume

Practitioners reported treating an average of 15.5 pediatric patients per week (14.5% of the 107 average total patient load). The distribution of pediatric practice volume was: 1-5 visits/week (34.2%), 6-10 visits/week (28.7%), 11-30 visits/week (31.4%), and 31+ visits/week (5.7%).

The age distribution of pediatric patients showed that school-aged children (5-12 years) were the most common group (34.2%), followed by toddlers/preschoolers (1-4 years) at 28.7%. Infants aged < 3 months comprised 15.2% of the patients, while 3-12 month infants represented 21.9% of the pediatric population.

Presenting Conditions by Age Group

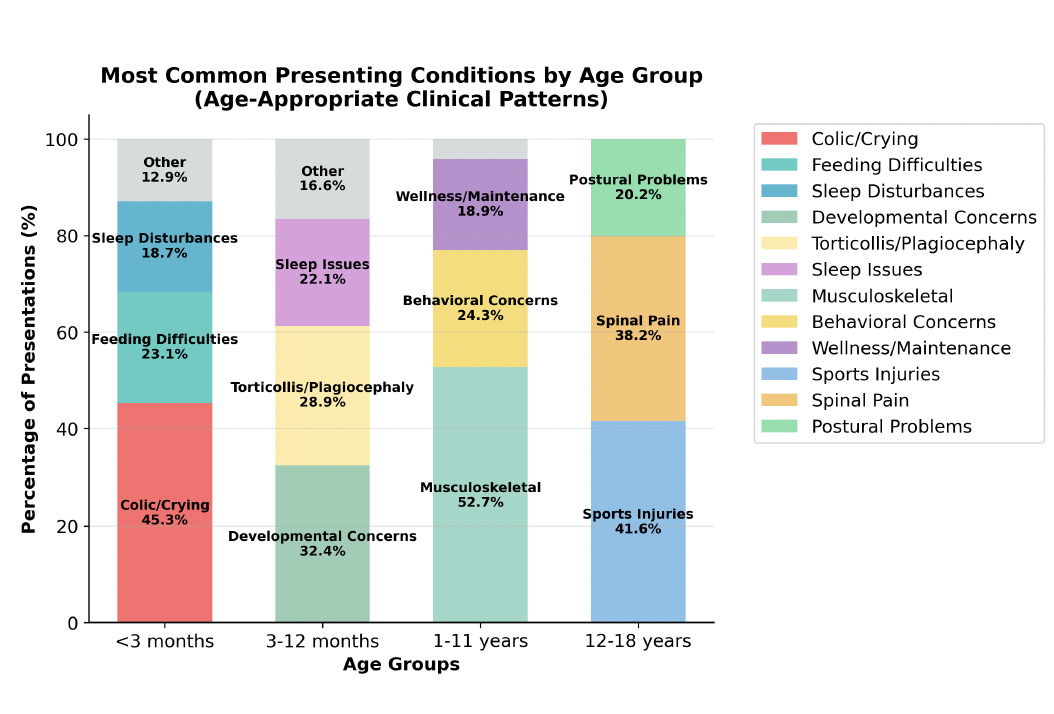

The presenting conditions (Figure 1) varied significantly by age group, reflecting developmental and age-related health patterns:

Infants <3 months: The most common presentations were colic and excessive crying (45.3%), feeding difficulties (23.1%), and sleep disturbances (18.7%).

Infants 3-12 months: Developmental concerns increased (32.4%), along with torticollis and plagiocephaly (28.9%), and persistent sleep issues (22.1%).

Children 1-11 years: Musculoskeletal complaints dominated (52.7%), with behavioral concerns (24.3%) and wellness/maintenance care (18.9%).

Adolescents 12-18 years: Sports-related injuries were most frequent (41.6%), followed by spinal pain complaints (38.2%) and postural problems (25.4%).

Treatment Approaches and Techniques

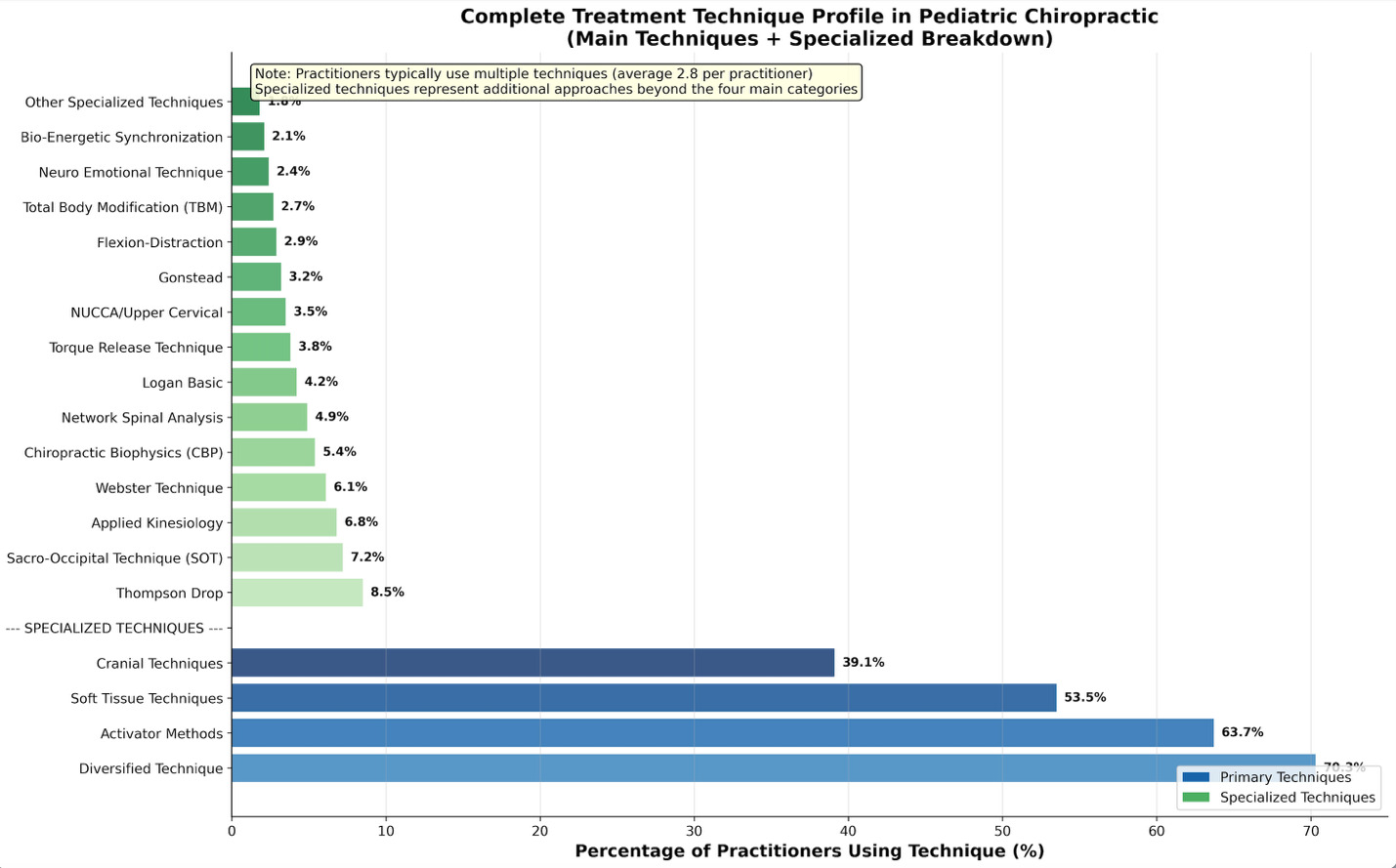

Practitioners utilized diverse treatment approaches (Figure 2), and employed multiple techniques. The most commonly used techniques were:

-

Diversified technique: 70.3%

-

Activator methods: 63.7%

-

Soft tissue techniques: 53.5%

-

Cranial techniques: 39.1%

-

Other specialized techniques: 25.8%

The provision of lifestyle advice was common, with practitioners offering dietary advice (50.1%), postural advice (49.6%), and exercise recommendations (48.4%).

Episode Characteristics and Time Allocation

The average episode of care consisted of 7.2 visits with the mode of 4.5. The initial consultation duration was typically 16-30 minutes (43.3%) or 31-60 minutes (40.2%), while return visits were commonly 11-15 minutes (37.9%) or 16-30 minutes (42.5%).

Perceived Outcomes and Safety Profile

Practitioners reported high rates of perceived improvement, with 94.3% of cases showing some degree of improvement. The breakdown of the perceived outcomes is

-

Significant improvement: 67.8%

-

Moderate improvement: 26.5%

-

No change: 3.5%

-

Worsening: 2.2%

Adverse events were reported in 2.1% of cases.

Economic Factors and Accessibility

The economic analysis revealed important accessibility considerations:

Cost Structure: Average episode cost (Table 1) was $326 USD in 2010 (approximately $496 USD in 2025 dollars), with initial visits averaging $56 USD in 2010 ($85 USD in 2025 dollars) and return visits averaging $38 USD in 2010 ($58 USD in 2025 dollars).

Four countries provided adequate sample size of financial data for robust statistical analysis (USA, UK, Canada and Australia) and represented the major English speaking markets for chiropractic care. Country-specific costs were as follows: United States $233 ± $100 (highest), United Kingdom $192 ± $71, Australia $191 ± $73, and Canada $160 ± $65 (lowest), representing a 46% variation from lowest to highest cost per country. Kruskal-Wallis test (Table 2) revealed statistically significant differences in episode costs across countries (H3=185.9, p < 0.001), and Dunn’s post-hoc test confirmed significant cost differences between all country pairs except Australia and the United Kingdom (all p < 0.001, except p = 0.895 for Australia vs. UK).

When expressed in local currencies, these costs represented $165 CAD in Canada, $208 AUD in Australia, £124 in the United Kingdom, and $233 USD in the United States.

Accessibility Measures: A substantial majority of practitioners (66.2%) offered reduced fees for pediatric patients, with average discounts of 20-30%, representing savings of approximately $82 per episode in 2010 ($124 per episode in 2025 dollars). Insurance coverage was available for 63.7% of patients, although coverage rates varied significantly by country and insurance system. When combining both fee reductions and insurance coverage, families’ effective out-of-pocket costs averaged approximately $167 per episode in 2010 ($253 per episode in 2025 dollars).

Healthcare Integration and Referral Patterns

Key findings included:

Referral Sources: The primary referral source was current patients and their families (80.4%).

Outgoing Referrals: A substantial majority (81.2%) of practitioners reported making referrals to other healthcare providers when appropriate.

Preventive Care: Most practitioners (85.5%) recommended periodic check-ups (Table 3), with 33.7% recommending monthly visits and 24.6% recommending three-monthly visits for maintenance care.

Training Level Correlations

Statistical analysis revealed significant correlations between practitioner training levels, (ranging from no pediatric training (18.3%), undergraduate only (28.6%), post-graduate seminar attendance (31.2%), and post-graduate certificate completion (21.9%)) and various practice characteristics:

Training and Practice Volume (r = 0.331, p < 0.001): Higher training levels showed a weak but statistically significant positive correlation with increased pediatric patient volume.

Training and Age Specialization (r = -0.208, p < 0.001): More highly trained practitioners showed a weak but statistically significant negative correlation (as training increased, age range treated decreased) with treating younger children, including infants.

Training and Perceived Outcomes (r = 0.180, p < 0.001): Higher training levels were associated with better perceived outcomes.

Training and Technique Diversity (r = 0.230, p < 0.001): More highly trained practitioners utilized a greater variety of treatment techniques, showing a weak but statistically significant positive correlation.

Discussion

This international survey provides an informative characterization of pediatric chiropractic practice patterns at the time of the survey and as such, may offer useful insights into clinical practice, training impacts, and healthcare integration. These findings may have salient implications for clinical practice, education, policy development, and future research directions.

Practice Patterns and Clinical Implications

Age-related variations in presenting conditions reflect normal developmental patterns and suggest that chiropractors address age-appropriate health concerns. The predominance of non-musculoskeletal conditions in infants (colic, feeding difficulties, sleep disturbances) and the shift toward musculoskeletal complaints in older children align with developmental physiology and parental health-seeking behaviors.19

The average number of pediatric visits per week 15.5 in this study place them at the higher end of data from general chiropractic surveys, and well below that reported in pediatric specific practices. Contemporaneous prior studies of general chiropractic practices in Canada27 and the USA28,29 reported 4, 14.1 and 13 visits per week respectively, whereas pediatric-specific practice survey respondents reported 28 and 43.3 pediatric visits per week.30,31 This may reflect that very few practitioners in this study were specialized in the pediatric patient.

Treatment time allocation may reflect the complexity of pediatric care, with practitioners spending adequate time on thorough assessment and age-appropriate care delivery.

The high utilization of multiple techniques (average 2.8 techniques per practitioner) suggests that pediatric chiropractic practice requires diverse clinical skills and adaptability to different patient presentations and ages. This finding supports the importance of comprehensive pediatric training, particularly within undergraduate chiropractic programs, that address multiple care approaches.32

Training and Education Implications

The statistically significant correlations between training level and practice characteristics, whilst modest in magnitude, provide consistent evidence for the value of specialized pediatric education. Practitioners with higher training levels treated more pediatric patients, were more likely to treat younger children, and reported better outcomes. These findings suggest that specialized training enhances both practitioner confidence and clinical competence as well as higher pediatric patient volumes.23 However, the weak correlation with perceived outcomes intimates that multiple factors influence treatment success beyond training alone.

The relationship between training and age specialization is particularly noteworthy because the care of younger children requires specialized knowledge of developmental anatomy, physiology, and age-appropriate care modifications. The finding that more trained practitioners are willing to care for infants suggests that educational programs successfully prepare practitioners for these challenging cases. Research has long noted that infants are the highest users of healthcare,33 including chiropractic care.22 Parents seeking care for their newborn highlights the importance of effective delivery of pediatric chiropractic education within undergraduate chiropractic programs worldwide.

Safety Considerations

An adverse event rate of 2.1% must be interpreted within the context of passive-surveillance limitations. Pohlman et al. demonstrated in North America that active surveillance detected adverse events in 8.8% of pediatric chiropractic visits compared to 0.1% with passive surveillance,16 similar to the 0.23% reported by European chiropractors.34 This suggests that the true adverse event rate may be higher than that previously reported, although the events detected through active surveillance were predominantly mild and transient. It must be noted that it is generally considered that any adverse event that does not require medical attention is not accurately defined as an adverse event, but as a side effect.35,36

The safety profile observed in this study aligns with systematic review findings showing rare adverse events in pediatric manual therapy populations.7 The age pattern of adverse events, with no serious events reported in children, supports the relative safety of pediatric chiropractic care delivered by appropriately trained practitioners.12

Economic Accessibility and International Healthcare Implications

It should be noted that in countries in this study where all public health care is free at the point of service (the UK) and chiropractic care is paid for privately at point of service, care givers still willingly presented and paid for their child’s chiropractic care.

Professional Commitment to Accessibility

The widespread implementation of reduced pediatric fees (66.2% of practitioners) combined with substantial insurance coverage (63.7%) demonstrates a strong professional commitment to economic accessibility across all countries studied. The average 20-30% discount for pediatric patients represents significant cost relief for families, with combined accessibility measures reducing out-of-pocket expenses from an average episode cost of $326 USD to approximately $167 USD in 2010 dollars ($253 USD in 2025 values). No known studies have been done as to whether chiropractic care for children is price sensitive. It should be noted that in countries in this study where all health care is free at the point of service, still demonstrated that parents presented their children for chiropractic care. The perception of cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care for children is proposed as a useful topic for future research.

Systematic Healthcare System Influences

The choice of Kruskal-Wallis testing and rank-based post-hoc analysis strengthens the reliability and policy relevance of the financial findings, ensuring that reported cost differences across countries reflect true healthcare system effects rather than statistical artifacts. This methodological rigor provides a defensible foundation for policy recommendations, supports guidance on equitable fee structures, and enhances the credibility of international comparisons for clinical and regulatory stakeholders. Healthcare system models influence cost structures in predictable patterns that align with the broader literature on healthcare economics.20 Canada’s single-payer universal healthcare system achieved the lowest costs ($160 USD), while the United States’ predominantly private insurance system resulted in the highest costs ($233 USD), representing a 46% variation. Australia and the United Kingdom, with their mixed public-private systems, demonstrated intermediate costs ($191-192 USD) that were statistically equivalent (p = 0.895), suggesting that hybrid models may achieve cost moderation through balanced public-private mechanisms.

Policy Implications and System-Level Interventions

These findings have substantial policy implications for improving pediatric healthcare accessibility. The systematic nature of cost differences indicates that healthcare policy interventions could significantly impact pediatric chiropractic accessibility more effectively than individual practitioner modifications could. Countries with higher costs may benefit from policy initiatives that promote affordability, such as expanded insurance coverage, regulated fee structures, or integration into universal healthcare frameworks. The relatively modest within-country variation compared with between-country differences suggests that system-level reforms, rather than individual practitioner education or incentive programs, represent the most promising avenue for addressing cost barriers. This finding supports policy-level interventions that address structural accessibility challenges rather than focusing solely on individual practice modifications.

International Standardization and Regulatory Considerations

International standardization efforts should consider these systematic healthcare system differences when developing practice guidelines and training requirements. The finding that Australia and the United Kingdom achieved statistically equivalent costs despite different healthcare system structures suggests that regulatory frameworks, professional standards, or other institutional factors may also influence cost structures beyond basic public-private distinctions.

Implications for Pediatric Healthcare Access

Economic accessibility varies substantially across healthcare systems, with important implications for families seeking pediatric chiropractic care. The systematic nature of these differences indicates that cost barriers are primarily structural rather than practitioner-driven, thus supporting the development of policy-level interventions to improve accessibility. The universal healthcare systems within this survey demonstrate superior cost-effectiveness for pediatric chiropractic care, suggesting that healthcare system design represents a critical determinant of pediatric healthcare accessibility that extends beyond individual practitioner or professional organization initiatives.

Healthcare Integration

The high rate of outgoing referrals (81.2%) demonstrated strong integration with the broader healthcare system and an appropriate recognition of the scope of practice. This collaborative approach is essential for comprehensive pediatric care and helps to ensure that children receive appropriate multidisciplinary treatment when needed.

The family centered referral pattern (80.4% of current patients/families) suggests high patient satisfaction and confidence in quality of care. This finding aligns with research showing 94% parental satisfaction rates with pediatric chiropractic care.18

Comparison with Previous Research

These findings complement and extend previous demographic research on chiropractors who treat children.2 While an earlier study characterized practitioner demographics, this investigation provides detailed clinical practice data that inform evidence-based practice development.

The perceived improvement rate of 94.3% aligns with parent-reported satisfaction studies18 and suggests consistency between practitioner and patient/parent perspectives regarding treatment outcomes. However, these findings must be interpreted cautiously given the subjective nature of perceived outcomes and potential reporting bias.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The survey relied on practitioner self-reports, which may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. Perceived outcome measures, which are valuable for understanding practitioner perspectives, do not represent validated clinical outcome measures.

The response rate and potential selection bias could not be fully assessed because of the distribution methods used. Practitioners who choose to participate may differ systematically from non-respondents in ways that could have influenced the findings.

The cross-sectional design provides a snapshot of practice patterns but cannot establish causal relationships or track changes over time. Longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into the evolution of practice and outcome trajectories.

Economic data reflect practitioner-reported costs and may not capture all the economic factors relevant to patients and healthcare systems. Data collection occurred in 2010 and was subject to factors such as inflation, economic outlook, and evolution of pediatric chiropractic care utilization.

Future Research Directions

This study identifies several important research priorities for pediatric chiropractic:

Prospective Outcome Studies: Long-term prospective studies using validated outcome measures are required to establish the effectiveness and safety profiles of chiropractic care.

Mechanism Research: Investigating the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the effects of the chiropractic adjustment in children would enhance our understanding of how chiropractic interventions influence pediatric health outcomes.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Formal economic evaluations comparing pediatric chiropractic care with conventional treatments would inform healthcare policies and resource allocation decisions.

Active Surveillance Systems: Implementation of active adverse event surveillance systems would provide more accurate safety data and support continuous quality improvement.

Standardized Outcome Measures: Development and validation of pediatric-specific outcome assessment tools will enhance research quality and clinical practice evaluation.

Clinical Practice Recommendations

Based on these findings, several recommendations emerge for clinical practice:

-

Specialized Training: The correlations between training and practice outcomes support the importance of specialized pediatric education for chiropractors treating children, particularly in the undergraduate chiropractic education space.

-

Age-Appropriate Approaches: The variation in presenting conditions by age group emphasizes the need for age-specific assessment and care protocols.

-

Multidisciplinary Integration: The high rate of referrals to other healthcare providers should be maintained and enhanced to ensure comprehensive pediatric care.

-

Economic Accessibility: The widespread implementation of reduced pediatric fees demonstrates professional commitment to accessibility and should be considered and expanded where possible.

-

Outcome Monitoring: Implementation of systematic outcome monitoring using validated measures would enhance clinical practice quality and support evidence-based care.

Conclusion

This international survey provides comprehensive insights into pediatric chiropractic practice characteristics, revealing diverse practice patterns with high perceived success rates and low adverse event rates. The statistically significant correlations between practitioner training and practice outcomes, though modest in effect size, support the importance of specialized pediatric education, particularly within the undergraduate phase. Economic accessibility measures have been widely implemented, demonstrating a professional commitment to equitable access to care.

The findings suggest that pediatric chiropractic practice is characterized by age-appropriate chiropractic care approaches, strong healthcare integration, and family centered care delivery. However, there is a need for more rigorous outcome research, standardized assessment tools, and active safety surveillance systems.

These results provide valuable evidence for the development of clinical practice, educational curriculum design, and healthcare policy. As pediatric chiropractic care continues to evolve, ongoing research and practice monitoring are essential to ensure optimal patient outcomes and professional development.

This study contributes significantly to the evidence base for pediatric chiropractic care and provides a foundation for future research and practice improvement initiatives. A comprehensive characterization of international practice patterns offers valuable insights for practitioners, educators, researchers, and policymakers working to advance pediatric chiropractic care.

Funding statement

No funding was received for this study

Conflicts of Interest declaration

No conflicts of interest were reported.

Author contributions

MD conceived the project, MD and JM contributed to the design and implementation of the research, MD produced the analysis and manuscript, MD, MM, and JM reviewed the manuscript.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) assisted technology was used for initial draft development.