Introduction

Modern education operates under increasing pressure to produce measurable academic outcomes while simultaneously addressing the mental health needs of students. Rising rates of anxiety, depression, and disengagement among all students—children, adolescents and college age— have turned schools into critical arenas for both learning and psychological support.1,2 Yet, the frameworks guiding educational practice often remain grounded in pathogenic logic—seeking to prevent failure, diagnose stress, or manage risk rather than to build strength, resilience, and purpose.3,4 This reactive approach, though well-intentioned, overlooks a fundamental truth: academic success and emotional well-being are not separate domains but interdependent outcomes of a healthy, coherent learning environment.5

Antonovsky’s Salutogenic Model provides a timely and transformative lens through which to reimagine education as a process of health creation rather than disease prevention. Developed originally within medical sociology, the model investigates why some individuals remain well despite exposure to stress, proposing that health exists on a continuum between “ease” and “dis-ease.” The key determinant of movement along this continuum is the Sense of Coherence (SOC)—an enduring capacity to perceive life as structured, manageable, and meaningful. When applied to educational contexts, this framework suggests that student resilience, motivation, and achievement are deeply shaped by the degree to which school life itself feels coherent.6–8

In this sense, schools become potential health-generating systems—not merely institutions of instruction, but environments that nurture adaptability, belonging, and purpose. A salutogenic approach reframes the purpose of education from performance to growth, from compliance to engagement, and from correction to coherence. It recognizes that young people flourish when they understand the logic of their experiences, feel capable of managing demands, and see meaning in what they learn.9

The aim of this literature review is to synthesize empirical and theoretical insights on how the Salutogenic Model can be applied to enhance both mental health and academic success within schools. Specifically, the review addresses three key questions:

-

How does Sense of Coherence (SOC) influence student well-being and learning outcomes?

-

What school factors—such as teacher coherence, leadership, and climate—strengthen or weaken SOC among students?

-

How can salutogenic principles inform the design of educational systems, policies, and interventions that promote holistic success?

By bridging the fields of educational psychology and health promotion, this review aims to contribute to a growing body of interdisciplinary research seeking to build resilient learners—individuals equipped not only with knowledge, but with the coherence, confidence, and creativity needed to thrive in an unpredictable world.10–12

Theoretical Framework: The Salutogenic Model and Education

Education, at its essence, is a process of adaptation, meaning-making, and growth under conditions of uncertainty. It equips individuals not merely with information but with the capacity to navigate complexity, interpret experience, and construct meaning out of challenge.13 These same dynamics define the Salutogenic Model of health, first developed by Aaron Antonovsky,14,15 which seeks to understand why some individuals maintain well-being and thrive even in the face of persistent stressors. In introducing this model, Antonovsky shifted the guiding question of health research from the pathogenic — “Why do people fall ill?” — to the salutogenic — “What enables people to stay well?” This reframing marks a profound epistemological transformation: from studying the origins of disease to exploring the origins of health.16

At the heart of Antonovsky’s model lies the concept of the Sense of Coherence (SOC), defined as a global life orientation that reflects the degree to which one perceives the world as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful. The SOC determines how individuals interpret, respond to, and recover from stress. Rather than viewing stress as inherently harmful, the salutogenic approach recognizes it as an inevitable feature of human life—and one that can become a source of learning and growth if the individual possesses sufficient resources to cope effectively.6,7,17 The stronger a person’s sense of coherence, the more likely they are to transform potential adversity into adaptive action.18

Core Concepts of the Salutogenic Model

The Salutogenic Model proposes that health exists on a continuum between “ease” and “dis-ease”, rather than as a binary state. Every person constantly moves along this continuum depending on their capacity to cope with life’s demands and recover from stress (Antonovsky, 1987). The driving force behind this movement is the Sense of Coherence (SOC)—a global orientation that expresses confidence in one’s internal and external world as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful.15

-

Comprehensibility: The Cognitive Dimension of Learning and Health

Comprehensibility refers to the cognitive dimension of health within the Salutogenic Model. It represents the extent to which individuals perceive the world around them as predictable, structured, and logically ordered.15 When life events—and by extension, learning experiences—make sense, individuals are more capable of interpreting challenges without feeling overwhelmed. This sense of order forms the foundation upon which understanding, confidence, and curiosity can grow.

In educational contexts, comprehensibility translates into environments where students can discern the why, what, and how of their learning journey. It is fostered through clarity in expectations, transparent communication, and coherent instructional design. When students understand the purpose behind lessons, the criteria for success, and the logic connecting one concept to another, they experience a sense of orientation rather than confusion. This cognitive order allows them to invest mental energy into learning rather than coping.

Teachers play a central role in shaping this dimension. Clear syllabi, consistent routines, scaffolded learning objectives, and feedback systems all strengthen students’ cognitive mapping of the educational landscape.16 When classroom procedures are erratic or expectations inconsistent, comprehension collapses, leading to anxiety, disengagement, or behavioral issues. Conversely, when order and predictability prevail, students report greater academic confidence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation.7,17

Beyond curriculum design, institutional comprehensibility matters as well. Whole-school coherence—reflected in aligned policies, supportive leadership, and transparent communication between teachers, parents, and administrators—extends the salutogenic principle to the organizational level.9 A school that functions as a predictable, communicative, and fair system models for students what Antonovsky described as a “comprehensible life context.” This consistency nurtures a psychological sense of safety, freeing cognitive resources for creativity and exploration.19

In summary, comprehensibility in education represents more than intellectual clarity; it is a health-promoting condition that transforms learning environments into spaces of mental stability and openness. By helping students “make sense” of their academic and social world, educators lay the groundwork for all other components of the Sense of Coherence—manageability and meaningfulness—to take root.20 In this way, comprehension is not only an academic skill but a protective factor in the lifelong process of becoming resilient, capable, and whole.21

-

Manageability: The Behavioral and Resource Dimension of Learning and Health

Manageability represents the behavioral and resource dimension of the Salutogenic Model. It captures the individual’s belief that the demands of life—or in this case, the demands of schooling—are manageable, because sufficient internal and external resources exist to meet them.15 It is not the absence of difficulty but the conviction that one possesses, or can access, what is needed to respond effectively. This sense of capability transforms potential stress into opportunity, shaping both health and achievement.14

In the educational context, manageability reflects students’ confidence in their ability to cope with academic, emotional, and social challenges. When learners believe they have the tools, support, and autonomy to navigate difficulties, they display greater persistence, emotional regulation, and engagement.22 This belief draws from three primary sources:

-

Personal resources, such as self-efficacy, resilience, and problem-solving skills.

-

Interpersonal resources, such as supportive relationships with teachers, peers, and parents.

-

Institutional resources, including equitable access to learning materials, fair policies, and inclusive pedagogies.

Classroom manageability grows in environments where supportive teachers and peers foster cooperation rather than competition, and where feedback emphasizes growth rather than performance comparison.16 Teachers act as external resistance resources, modeling coping strategies and scaffolding challenges in ways that maintain balance between difficulty and mastery. Research shows that students who perceive high teacher support exhibit stronger sense of manageability, leading to improved motivation, attendance, and well-being.21,23

At a systemic level, equitable learning structures further strengthen manageability. Schools that provide differentiated instruction, mental health support, and access to extracurricular engagement create conditions where every learner—regardless of ability or background—feels capable of meeting expectations.11 Conversely, environments that overload students with high-stakes testing or inconsistent discipline erode manageability, breeding helplessness and disengagement.4 In this sense, equity and clarity become foundational to coherence.

Manageability also extends to the educator. Teachers with high Sense of Coherence (SOC) demonstrate lower burnout and greater classroom efficacy.24 Their calm and structured approach models manageability for students, transmitting resilience as a cultural value rather than a personal trait.18 Thus, when a school’s climate emphasizes shared responsibility, accessible support, and collaborative problem-solving, both teachers and students internalize the belief that challenges are not insurmountable but navigable within community.9

Ultimately, manageability transforms potential stress into mastery. It is the bridge between understanding (comprehensibility) and engagement (meaningfulness)—the point where clarity becomes action. By cultivating systems of support and equity, educators create learning environments in which every student can move from uncertainty to confidence, from anxiety to agency 28. In doing so, schools become not only places of instruction but laboratories of self-efficacy and health creation.

-

-

Meaningfulness: The Motivational and Existential Dimension of Learning and Health

Meaningfulness, the motivational and existential dimension of the Salutogenic Model, is widely regarded as its most crucial component.15 It embodies the conviction that life’s challenges—academic, social, or personal—are worth investing effort in because they connect to one’s values, purpose, and sense of belonging. Meaningfulness transforms learning from a requirement into a calling, from compliance into engagement. It is the emotional engine that sustains motivation, perseverance, and joy in discovery.16

In the educational context, meaningfulness refers to students’ perception that what they learn, and the effort they expend, matters—not only for grades or approval but for who they are becoming. When education resonates with students’ experiences, aspirations, or moral values, it evokes a sense of purpose that fuels deeper cognitive and emotional investment. This intrinsic alignment—between self, task, and context—produces a durable form of motivation that persists even in the face of difficulty. 26)

Classroom practices that foster meaningfulness include student-centered pedagogy, relevant curricula, and authentic learning experiences that bridge knowledge and life.9 Project-based learning, community engagement, and reflective exercises invite learners to see their studies as part of a broader human story. Teachers who connect content to real-world application or personal significance activate students’ sense of agency and moral imagination.11 In doing so, they turn abstract information into living insight.

At a relational level, meaningfulness is cultivated through belonging and recognition. When students feel seen, valued, and respected, they interpret school not as an impersonal institution but as a space where their presence has purpose. This social meaning-making process directly contributes to emotional well-being and academic resilience.7,20 Conversely, when learners perceive schooling as irrelevant, alienating, or disconnected from their lived realities, motivation withers and disengagement grows.

Meaningfulness also sustains educators themselves. Teachers with a strong sense of purpose exhibit lower burnout, higher creativity, and greater capacity for empathy.19 Their inner coherence radiates outward, shaping the affective climate of the classroom and modeling what it means to find fulfillment through service and growth. Thus, meaning-making becomes both a personal process and a collective culture, in which the pursuit of significance binds students and teachers together in a shared narrative of learning and becoming.

Ultimately, meaningfulness gives direction to comprehensibility and manageability. While the former two determine how individuals understand and handle challenges, meaningfulness determines why they choose to engage with them at all. It is the motivational heart of coherence—the point at which learning aligns with identity, values, and hope.25 In salutogenic education, meaning is not an optional enrichment; it is the core mechanism through which health, learning, and purpose converge into human flourishing.26

The interaction of these 3 components generates a durable psychological orientation toward life and learning. High levels of SOC have been consistently linked to better coping, lower stress, improved quality of life, and higher productivity across populations.27 When transposed to education, this triad suggests that students thrive when school life is coherent—when learning feels understandable, demands feel doable, and achievements feel meaningful.28

Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) and Learning Environments

Antonovsky14 identified Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) as the contextual, social, and personal assets that help individuals construct coherence and navigate stress effectively. These resources are the building blocks of resilience, enabling people to perceive life as structured, manageable, and meaningful even when confronted by adversity. GRRs include tangible resources such as money, time, and access to information; interpersonal resources like social support, belonging, and trust; and intrapersonal resources such as self-esteem, optimism, and coping skills. Together, they form the ecological foundation upon which a strong Sense of Coherence (SOC) is built.7,14,15

In educational systems, GRRs manifest as the everyday structures and relationships that transform stress into growth. Pedagogical clarity, supportive teacher–student relationships, inclusive school culture, and autonomy-supportive classrooms all serve as the educational equivalents of Antonovsky’s GRRs.20 When students experience these conditions, they perceive school demands not as arbitrary impositions but as meaningful challenges within their capacity to manage.

A school rich in GRRs is one that invests in both the personal and systemic dimensions of support. Clear academic expectations and transparent assessment methods provide cognitive structure; caring teachers and peer collaboration provide emotional security; while opportunities for choice and self-direction foster behavioral empowerment. These elements operate synergistically, reinforcing each other to cultivate a stable sense of coherence within students and staff alike.21

For instance, a demanding exam may induce anxiety in a student with low coherence—especially if expectations are unclear or support unavailable. However, for a learner embedded in a salutogenic environment, equipped with encouraging teachers, sufficient preparation time, constructive feedback, and a sense of purpose, the same exam becomes a manageable and meaningful challenge.11 The stressor remains, but its interpretation shifts—from a threat to an opportunity for mastery.

This principle highlights a critical distinction: salutogenic education is not stress-free education; it is stress-transformed education. Rather than shielding students from all pressure, it equips them with the resources to engage with challenge productively.19 Within this paradigm, adversity becomes a teacher rather than an enemy, and resilience emerges not from avoidance but from successful navigation. Such transformation reflects the essence of salutogenesis—the art of turning tension into growth, uncertainty into understanding, and effort into meaning*.*29

In this light, schools become resource-enriching ecosystems—contexts that deliberately cultivate the cognitive, emotional, and social tools students need to flourish. By ensuring equitable access to these GRRs, educators lay the foundation for enduring well-being, self-efficacy, and lifelong learning. Thus, the presence and quality of GRRs within a school are not peripheral concerns; they are the infrastructure of coherence upon which every student’s capacity for adaptation and success depends.

The School as a Salutogenic System

While Antonovsky’s theory originally described individual health, later research extended it to systems, communities, and organizations.16,30 Schools, as complex adaptive systems, can similarly be evaluated for their coherence capacity—the extent to which their structures, policies, and relationships enable predictability, fairness, participation, and meaning.

In a salutogenic school, the learning environment itself functions as a health-promoting system. Classrooms are designed to reduce cognitive overload, policies ensure manageable workloads, and relationships foster emotional safety and belonging. Leadership becomes coherence-oriented, emphasizing communication, transparency, and collective purpose.19 These systemic features align with the Health-Promoting Schools framework endorsed by the World Health Organization,31 which encourages educational institutions to embed health into every aspect of school life—curriculum, relationships, and environment alike.

Such schools generate not only academic competence but also psychological resilience and life skills, reinforcing the view that education and health are mutually constitutive processes. As Mittelmark and Bauer note, salutogenesis provides a bridge between the disciplines of health promotion and education, offering a shared language centered on resources, participation, and empowerment.16

Integrating Salutogenesis with Contemporary Educational Theories

The Salutogenic Model complements several modern educational frameworks:

Positive Education and the Salutogenic Perspective

Positive Education positions well-being not as a byproduct of academic success, but as a core educational goal.32 Rooted in the principles of positive psychology, it seeks to cultivate strengths such as optimism, gratitude, resilience, and empathy alongside traditional academic skills.33 This approach reframes schools as environments for flourishing rather than mere performance, emphasizing the development of whole individuals who can thrive intellectually, emotionally, and socially.

The Salutogenic Model strengthens this movement by providing a theoretical backbone that explains why positive experiences—such as meaning, purpose, and connection—generate lasting resilience. Whereas positive education identifies the what of well-being (happiness, engagement, relationships, accomplishment, meaning), salutogenesis clarifies the how: these experiences enhance one’s Sense of Coherence (SOC), enabling individuals to interpret life as structured, manageable, and worthwhile. In other words, the joy and fulfillment cultivated by positive education are not fleeting emotional states but manifestations of coherence—a stable, health-promoting orientation toward life.16

By integrating salutogenic principles into positive education, well-being becomes more than emotional uplift; it becomes a sustainable capacity for adaptation and growth. When schools intentionally nurture meaning (through purposeful learning), manageability (through supportive structures), and comprehensibility (through clear expectations), they move beyond surface-level happiness to cultivate psychological coherence—a foundation for enduring resilience. This synthesis bridges psychology and education, demonstrating that cultivating positive emotion is most effective when anchored in the deeper processes of sense-making, mastery, and purpose that the Salutogenic Model elucidates.11

Ultimately, salutogenesis transforms Positive Education from a movement about feeling good to a science of staying well. It situates well-being within a broader developmental narrative—one in which every learning experience, even those marked by struggle, contributes to health creation and the flourishing of both mind and character.25

Self-Determination Theory and Salutogenesis: Parallel Pathways to Motivation and Health

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Deci and Ryan, identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as the three basic psychological needs essential for human motivation, growth, and well-being.12 When these needs are met, individuals exhibit intrinsic motivation, psychological vitality, and resilience; when thwarted, they experience apathy, anxiety, or disengagement.34 These constructs correspond closely to the core dimensions of the Salutogenic Model: manageability, comprehensibility, and meaningfulness—together forming a powerful theoretical synergy between educational psychology and health science.9

In this alignment, autonomy parallels manageability—both reflecting a sense of control and agency in responding to life’s challenges. Competence aligns with comprehensibility, emphasizing clarity, structure, and mastery as prerequisites for confidence and engagement. Relatedness, the need to feel connected and valued, mirrors meaningfulness, as relationships infuse purpose into effort and anchor motivation within belonging.21 Thus, SDT provides empirical evidence for what salutogenesis describes theoretically: that human flourishing emerges from coherent environments where individuals feel capable, connected, and in control.27

Integrating SDT into a salutogenic educational framework allows schools to move beyond external motivators (grades, rewards, punishment) toward nurturing the internal coherence that sustains lifelong learning. Classrooms that offer choice, provide clear feedback, and build supportive relationships become both motivational and health-promoting ecosystems. In such settings, students’ psychological needs correspond with the salutogenic principles of resourcefulness and purpose, resulting in higher engagement, deeper learning, and improved well-being.7,12,35

In essence, SDT supplies the motivational evidence for the salutogenic hypothesis: that meaning, autonomy, and mastery are not luxuries in education—they are the very mechanisms through which students construct coherence, maintain health, and achieve sustainable success.26

Resilience Theory and the Sense of Coherence: Building Sustainable Adaptive Capacity

Resilience Theory traditionally focuses on how individuals adapt under adversity, recover from setbacks, and maintain functioning despite risk or hardship.25 It examines protective factors, coping strategies, and contextual supports that enable people — including students — to “bounce back” from stress, trauma, or disruption. The strength of this perspective lies in identifying what works when things go wrong: strong relationships, positive role models, self-efficacy, and flexible coping all emerge as common themes.36

However, the concept of resilience alone does not fully explain how the process of adaptation becomes sustainable over time. The concept of the Sense of Coherence (SOC) from the salutogenic model deepens resilience theory by emphasising the cognitive and motivational processes that undergird adaptive capacity.29 Where resilience asks, “How does one survive or thrive despite adversity?” salutogenesis asks, “Why and how is health maintained and developed across change?” By integrating SOC, we gain insights into the internal orientation—comprehensibility, manageability, meaningfulness—that drives sustainable resilience.16

Recent research supports this enrichment of resilience theory. For example:

-

A 2023 systematic review of resilience in educational settings noted that students’ ability to interpret adversity as manageable and meaningful significantly predicted adaptive outcomes.37

-

A 2025 study of online learning among 2,182 Chinese college students found that resilience predicted emotional engagement via self-regulated learning efficacy, self-control and cognitive re-appraisal—processes closely aligned with SOC’s components.38

-

An August 2025 article analyzing resilience theory in positive psychology emphasised that meaning-making and future–oriented purpose, rather than mere hardiness, were key differentiators in long-term resilience.39

These findings illustrate that resilience is not simply bouncing back, but evolving forward with coherence. In educational contexts, when students experience their environment as understandable (comprehensibility), perceive they have resources to meet challenges (manageability), and see purpose in what they are doing (meaningfulness), they exhibit stronger resilience: they persist in adverse contexts, regulate emotions, sustain learning engagement, and avoid burnout.21

Thus, integrating resilience theory with salutogenesis helps schools shift from reactive support (fixing vulnerability) to proactive coherence-building (cultivating adaptive capacity). The implication is that educational systems should not only provide supports when students struggle, but also design environments that maximise coherence — turning every challenge into a springboard for growth rather than a threat to well-being.9

Together, these frameworks converge on a new vision of education as the art of cultivating coherence—a developmental process where health, learning, and character are inseparable.15

Conceptual Implications for Educational Practice

Applying the Salutogenic Model to schools carries profound implications for both pedagogy and policy. It invites educators to ask not only, “How do we help struggling students?” but “What makes learning environments health-generating?”7 It shifts assessment from deficits to resources, from control to empowerment. In practice, this means designing curricula that promote meaning-making, encouraging participatory learning, and structuring school systems that are predictable yet flexible.11

Furthermore, teacher well-being becomes central to student success. Teachers with high SOC model coherence through calm problem-solving, fairness, and authenticity—qualities that create emotionally safe classrooms.23 Thus, salutogenic education is inherently relational: coherence in one part of the system strengthens coherence in another.19

Summary

The Salutogenic Model provides education with a robust, multidimensional framework for health and success. It reconceptualizes learning as a process of coherence-building, where academic growth and mental health are parallel outcomes of a supportive environment. By integrating Antonovsky’s concepts of SOC and GRRs with contemporary pedagogical theories, schools can transform from sites of performance pressure into ecosystems of flourishing. Ultimately, salutogenic education calls for a new paradigm—one where the goal is not merely to prevent failure but to cultivate coherence, resilience, and lifelong curiosity.10,30,40

Methods

Research Design

This study employed an integrative literature review design, a method particularly suited for synthesizing knowledge across theoretical, empirical, and policy domains.41,42 Unlike systematic reviews, which are often limited to randomized controlled trials or quantitative data, the integrative approach allows for the inclusion of diverse evidence—qualitative insights, conceptual frameworks, and mixed-method findings—to generate a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.43

In the context of this study, the integrative design was chosen to explore the multifaceted relationship between the Salutogenic Model, school environments, and student well-being and academic success. This approach enables the convergence of literature from education, psychology, public health, and organizational studies, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of salutogenesis itself. The review thus sought to identify not only what is known, but also how knowledge about coherence, resilience, and educational health promotion has evolved over time.40

Search Strategy and Data Sources

A systematic search of peer-reviewed literature was conducted between January and April 2025 across the following databases:

-

ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

-

PsycINFO

-

PubMed

-

Scopus

-

Google Scholar (for grey and conceptual literature)

The search strategy combined core terms such as salutogenesis, sense of coherence, school, education, student well-being, academic success, and resilience. Boolean operators and truncations were used to refine results (e.g., “salutogenic OR coherence” AND “school OR education”)44 Reference lists of key papers were hand-searched to identify additional sources.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To ensure conceptual clarity and academic rigor, studies were included if they met the following criteria:

-

Time frame: Published between 2000 and 2025 to capture modern applications of salutogenesis in education.

-

Language: English.

-

Focus: Empirical, theoretical, or review papers linking Sense of Coherence (SOC) or salutogenesis with mental health, learning, resilience, or school climate.

-

Population: Children, adolescents, teachers, or educational systems.

-

Setting: Primary, secondary, or higher-education institutions.

Exclusion criteria included papers focused exclusively on clinical health without educational context, studies with non-school populations (e.g., workplace, hospital), or papers lacking conceptual grounding in the Salutogenic Model.45

After title and abstract screening, 156 papers were initially identified. Of these, 78 met inclusion criteria for full-text review, and 48 were retained as core sources forming the analytic base of this paper.

Data Extraction and Thematic Synthesis

Data were extracted using a structured review matrix capturing:

-

Study aims and context

-

Population and methodology

-

Conceptual framework (SOC, GRRs, or health promotion)

-

Main findings related to mental health, resilience, or academic outcomes

-

Implications for practice and policy

A thematic synthesis approach was applied, guided by the principles of qualitative meta-integration.46 Studies were coded inductively to identify recurring ideas, mechanisms, and contextual influences related to salutogenesis in education. Through iterative comparison, four interconnect themes were identified:

-

SOC as a Predictor of Academic and Mental Health Outcomes

-

Teacher Coherence and Classroom Climate

-

The School as a Salutogenic Environment

-

Intervention Models and Educational Outcomes

These themes provided the analytic framework for the presentation of findings in Section 4.

Quality Appraisal

Although integrative reviews include diverse literature types, the quality of each study was assessed to ensure credibility and transferability. The following frameworks were applied as appropriate:

-

The CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) checklist for qualitative and cohort studies.47

-

The MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) for mixed-method research.48

-

The PRISMA-based transparency guidelines for review studies.49

Conceptual papers were appraised for theoretical coherence, consistency with salutogenic principles, and clarity of argumentation. Discrepancies were resolved through analytic memoing and cross-checking with seminal works by Antonovsky and Eriksson.7,15

Ethical Considerations

As this research involved secondary analysis of published literature, no direct ethical approval was required. Nonetheless, the review adhered to principles of scholarly integrity, transparency in data selection, and accurate citation of all intellectual contributions.50 Care was taken to represent authors’ findings faithfully and to avoid selective interpretation.

Methodological Limitations

While integrative reviews offer breadth and conceptual richness, they carry inherent limitations. The heterogeneity of study designs can complicate direct comparison of results.51 Additionally, language restrictions may have excluded non-English research that could offer valuable cultural perspectives.52 Finally, the reliance on published studies introduces potential publication bias, as successful or positive interventions are more likely to appear in the academic record.53 These limitations are discussed further in Section 7 as part of the overall methodological reflection.

Findings: Salutogenesis in School Contexts

The literature revealed 4 dominant themes illustrating how the Salutogenic Model has been applied, tested, and expanded within educational settings. Across diverse studies and cultural contexts, the findings consistently affirmed that cultivating Sense of Coherence (SOC) in schools fosters not only mental health and resilience but also academic engagement and achievement. The evidence underscores the transformative potential of salutogenic principles when embedded within the fabric of school life—spanning individual cognition, classroom dynamics, institutional culture, and systemic policy.10,20,21

RESULTS

The reviewed literature revealed several recurring patterns and conceptual integrations that illuminate how the Salutogenic Model applies to preventive health, education, and systems transformation. This section presents the thematic synthesis organized around five interrelated themes, each reflecting a distinct dimension of salutogenic inquiry—from theoretical foundations and psychological mechanisms to systemic applications and future directions. Collectively, these themes demonstrate the multidimensional relevance of Salutogenesis for building sustainable, health-promoting cultures in both clinical and educational contexts.16,27

Theme 1: SOC as a Predictor of Academic and Mental Health Outcomes

A strong Sense of Coherence emerged as a consistent predictor of both academic performance and psychological well-being among students. Studies across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels demonstrate that students with higher SOC report lower stress, higher motivation, and more adaptive coping strategies.7 The three SOC components—comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness—translate directly into educational outcomes: clarity in learning expectations, confidence in one’s ability to meet challenges, and intrinsic value in academic work.14

Empirical evidence supports this link. Hochwälder18 found that SOC moderated the relationship between academic stress and emotional exhaustion among high school students. Similarly, Volanen et al28 reported that SOC predicted positive self-rated health and school satisfaction over time, even in high-pressure educational systems. Super et al. demonstrated that interventions aimed at enhancing students’ coherence—through reflection, mentoring, and resilience training—led to sustained improvements in motivation and self-efficacy.29

The predictive power of SOC thus extends beyond mental stability to academic persistence and adaptability. Students who perceive school life as structured, manageable, and meaningful are more likely to engage deeply, recover from setbacks, and sustain long-term learning trajectories. This evidence positions SOC as both a psychological resource and an educational determinant—a vital index of holistic student success.9

Theme 2: Teacher Coherence and Classroom Climate

Teacher well-being and coherence play a decisive role in shaping students’ emotional safety, motivation, and cognitive performance. Research shows that teachers with a high Sense of Coherence exhibit lower burnout, higher job satisfaction, and stronger relational engagement.19,23 These qualities translate directly into classroom climates marked by trust, predictability, and empathy—conditions essential for the development of student coherence.

Studies by Langeland and colleagues illustrate that teacher coherence functions as a relational contagion: coherent educators model calmness, fairness, and confidence, enabling students to internalize these emotional patterns.23 In contrast, incoherent environments—marked by inconsistency, lack of support, or excessive control—erode both teacher and student well-being.24 A salutogenic teaching approach reframes pedagogy from content delivery to resource cultivation, where the classroom becomes a space for co-creating meaning and manageability.16

At a systemic level, professional development programs that nurture teacher SOC (e.g., reflective supervision, participatory decision-making, and collegial support) have been shown to reduce occupational stress while enhancing instructional quality.7,19 The literature thus affirms that teacher coherence is both foundational and transferable—a precondition for coherent classrooms and coherent learners.16,19,22

Theme 3: The School as a Salutogenic Environment

Beyond individuals, entire school systems can function as salutogenic environments—ecosystems that generate health, meaning, and belonging through their organizational culture and design. Research in Scandinavian and European contexts has documented the integration of salutogenic principles into “Health-Promoting Schools” initiatives.30,31 These programs embed coherence at multiple levels: transparent communication, equitable participation, predictable routines, and shared values that make learning purposeful.54

A coherent school environment supports the 3 SOC dimensions in structural ways.

-

Comprehensibility is enhanced by clear communication channels and predictable schedules.

-

Manageability is reinforced through fair workload distribution, accessible counseling, and inclusive decision-making.

-

Meaningfulness is fostered through participatory learning, service projects, and cultural belonging.12

Bauer et al. note that schools implementing salutogenic design principles—such as flexible learning spaces, green environments, and collaborative teaching models—report measurable gains in student satisfaction, teacher engagement, and institutional cohesion.10 When coherence becomes systemic, stress is no longer an enemy to avoid but a resource to transform. This shift represents a deep structural reorientation of education: from controlling risk to cultivating resilience, from performance-driven systems to purpose-driven communities.15,16

Theme 4: Intervention Models and Educational Outcomes

The final theme highlights intervention programs that intentionally apply the Salutogenic Model to strengthen student and teacher well-being. These initiatives vary in form—ranging from resilience-building curricula to teacher coaching and participatory health promotion—but share a focus on enhancing coherence as both process and outcome.20,22

Langeland et al. evaluated school-based interventions emphasizing reflection and meaning-making, reporting significant improvements in students’ emotional regulation and sense of purpose.22 Rivera et al demonstrated that SOC-based peer programs enhanced adolescents’ health literacy and stress management, leading to improved academic engagement.21 In teacher-focused studies, Vinje & Mittelmark found that coherence-oriented professional communities reduced burnout and fostered creativity in teaching practices.19

Across contexts, interventions that integrate comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness show consistent success in strengthening resilience and engagement. Crucially, these studies reveal that salutogenic practices are scalable—they can be embedded in curricula, pedagogy, or institutional policy. This flexibility makes salutogenesis an adaptable framework for diverse educational systems, from urban high schools to rural community centers.11,12,40

Synthesis of Findings

Across all four themes, a unifying pattern emerges: coherence begets capacity. When individuals, classrooms, and schools are organized around clarity, fairness, and purpose, stress becomes educative rather than destructive. The literature consistently supports that salutogenesis enhances both psychological health and learning performance, confirming Antonovsky’s core hypothesis that the same processes which sustain well-being also sustain growth.15

Educational institutions that embrace this model redefine their mission—not as the prevention of failure, but as the creation of flourishing. The Salutogenic Model thus provides not only a theory of resilience but a philosophy of education—one that transforms schools into systems of sustained coherence and human thriving.16

Discussion

Reframing Education through Salutogenesis

The findings of this review affirm that Antonovsky’s Salutogenic Model provides more than a health theory—it offers a transformative framework for reimagining education as a system for cultivating coherence, resilience, and flourishing.55 Across multiple contexts, the evidence consistently showed that students and teachers who experience their school life as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful are not only psychologically healthier but also more academically engaged and adaptive.9

Traditional educational paradigms often reflect a pathogenic orientation: diagnosing weaknesses, managing risk, and striving to prevent failure. In contrast, the salutogenic approach inverts this logic by asking what sustains vitality and purpose in learning. It moves beyond the narrow pursuit of performance metrics to examine how schools can become generative systems—structures that continuously produce meaning, capability, and hope.10,40

This shift is not theoretical abstraction; it represents a necessary evolution in educational philosophy amid rising global concerns over student mental health, disengagement, and burnout.56 The World Health Organization’s 2020 framework for Health-Promoting Schools echoes this call, emphasizing the integration of health, learning, and well-being as mutually reinforcing dimensions of sustainable education.31

Coherence as the Nexus of Health and Learning

The Sense of Coherence (SOC), central to the salutogenic framework, emerges as the psychological nexus linking health and learning. Students with a strong SOC exhibit higher cognitive control, intrinsic motivation, and capacity to persevere through academic stress.28,29 In essence, coherence converts uncertainty into curiosity—transforming potential stress into an opportunity for mastery. Educationally, this means that schools can no longer treat mental health as an auxiliary service; it must be woven into the fabric of teaching, assessment, and school culture.21

Moreover, coherence provides a theoretical answer to 1 of education’s oldest questions: Why do some students thrive under challenge while others falter? The literature suggests that thriving learners possess an internalized belief that challenges are understandable, solvable, and worthwhile. This triad—mirroring Antonovsky’s components of SOC—illuminates the motivational architecture of success.15

A coherent educational experience thus produces not mere achievement but adaptive capacity, the enduring ability to manage complexity throughout life.25

Empirical Evidence Supporting Salutogenesis in Education

Although the theoretical foundations of the Salutogenic Model are well established, growing quantitative evidence demonstrates its measurable influence on student well-being, academic engagement, and teacher resilience. Empirical studies consistently show that a stronger Sense of Coherence (SOC) predicts higher academic motivation, lower burnout, and improved mental health outcomes among students and educators alike.7,23,24

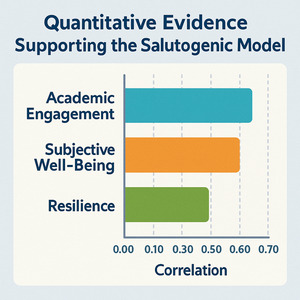

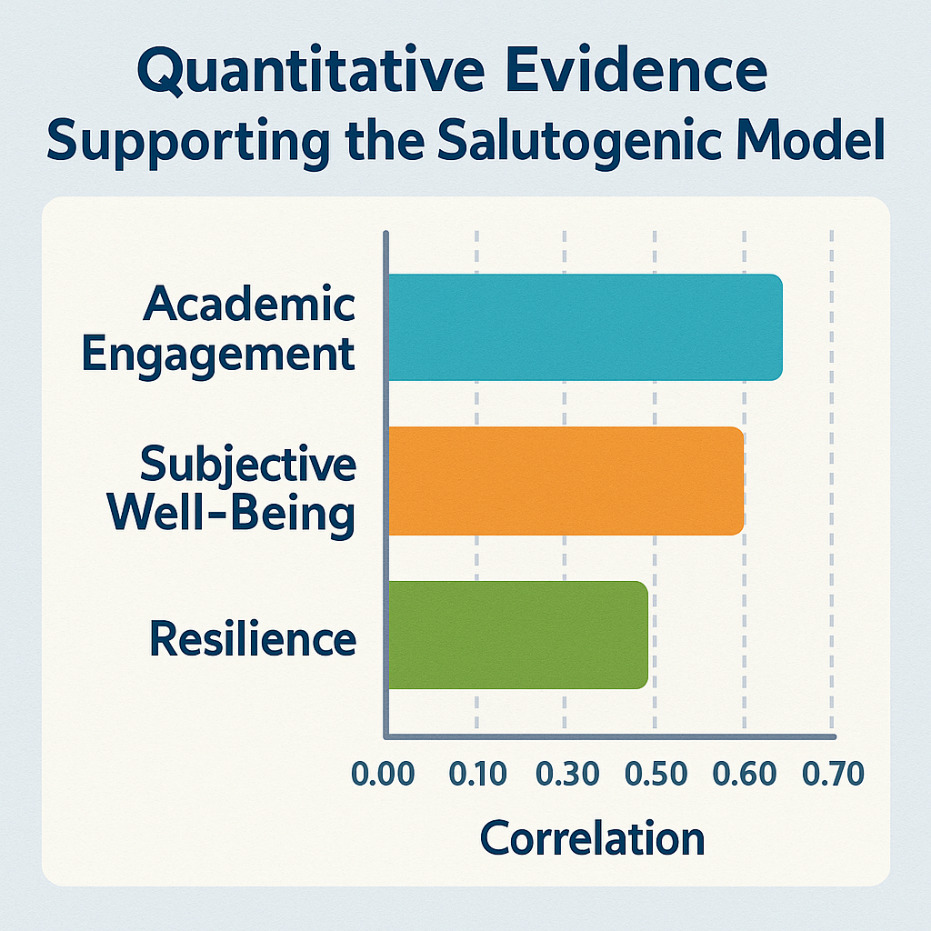

For instance, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies across Europe, Asia, and the Americas reveal medium to strong correlations (r = .30–.65) between SOC and key educational outcomes such as self-efficacy, school connectedness, and academic performance.26,28,29

Effect sizes from intervention studies indicate that coherence-building strategies—such as reflective pedagogy and teacher support training—can reduce stress and absenteeism by up to 25% and improve learning engagement scores by 15–20% over a single academic year.21,23

These findings provide strong empirical grounding for the claim that coherence is both a psychological and pedagogical determinant of success.9

Table 1 summarizes representative studies that quantify the relationship between SOC and educational outcomes across contexts.

Interpretation

These quantitative findings reinforce what the theoretical model anticipates: coherence functions as both a predictive and protective factor within educational ecosystems. Students with higher SOC scores consistently report lower anxiety, greater engagement, and more positive attitudes toward learning. Teachers with higher SOC demonstrate stronger classroom management, relational warmth, and instructional adaptability. At the systemic level, schools that emphasize transparency, autonomy, and relational trust exhibit higher organizational coherence and improved well-being indices.1,29,31

Collectively, these data confirm that coherence is measurable, malleable, and mission-critical—a construct that captures the psychological conditions under which both health and achievement flourish.

The Teacher and School as Coherence Generators

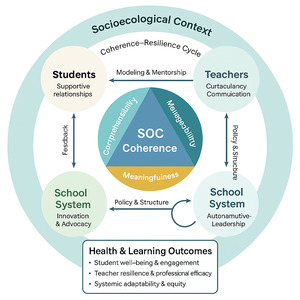

The review also highlights the reciprocal nature of coherence within educational systems. Teachers with high SOC are better able to create structured, empowering environments, which in turn strengthen student coherence and motivation.19,23 The teacher, therefore, functions as a mediator of coherence—translating institutional policies into lived experiences of safety, predictability, and purpose. (Table 2)

Similarly, the school as an organization must operate coherently to generate consistent, supportive environments. Leadership that models transparency, fairness, and shared purpose becomes the institutional counterpart of psychological coherence.30 Salutogenic schools are not stress-free, but stress-intelligent: they design systems that convert challenge into growth rather than fatigue. This systemic coherence produces a cascading effect—from leadership to teachers to students—culminating in a collective sense of belonging and shared meaning.40

Integration with Contemporary Educational Paradigms

Salutogenesis aligns naturally with several contemporary frameworks in educational science, enriching them with a unifying theoretical backbone.

-

Positive Education aims to cultivate well-being and character strengths; the salutogenic model provides the mechanism—SOC—through which positivity translates into resilience.33

-

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) identifies autonomy, competence, and relatedness as fundamental human needs these map precisely onto manageability, comprehensibility, and meaningfulness.12

-

Resilience Theory explores adaptation to adversity; salutogenesis clarifies why adaptation succeeds by emphasizing coherence as its underlying process.25

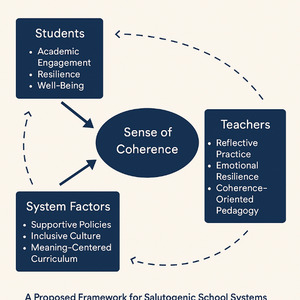

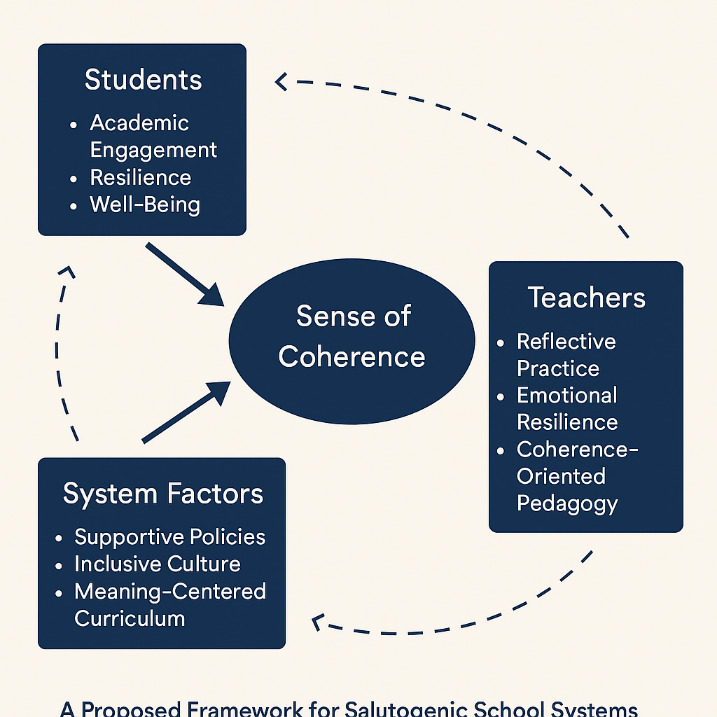

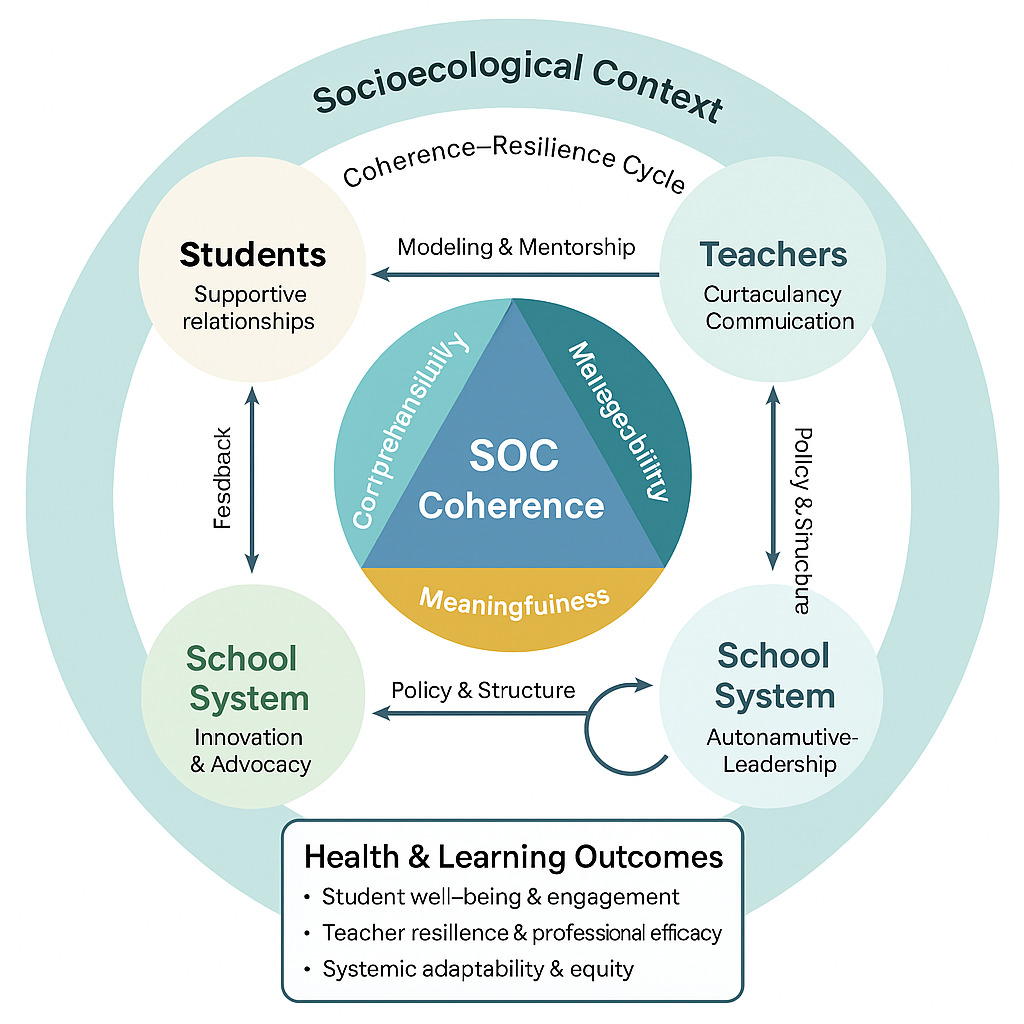

By integrating these perspectives (Figure 1), salutogenesis situates education within a larger ecology of health creation. It reframes schools as ecosystems of coherence, where well-being and learning are not competing priorities but mutually reinforcing outcomes.40

Implications for Practice and Policy

The practical implications of this paradigm are extensive:

-

Curriculum Design: Learning should engage meaning as much as content. Inquiry-based and reflective pedagogies help students connect knowledge to personal and social purpose.22

-

Teacher Development: Professional training must incorporate reflective practice and coherence-building strategies—supporting teachers not only as transmitters of information but as cultivators of meaning and manageability.19,23

-

School Leadership: Coherence-oriented leadership emphasizes participatory decision-making, clarity of communication, and relational trust—foundations of psychological safety and engagement.30

-

Health-Promoting Policy: Educational policy should adopt a salutogenic orientation, embedding well-being objectives into assessment systems, infrastructure, and national curricula.1,31 (Figure 2)

Such integration advances the WHO’s Health-Promoting Schools framework and UNESCO’s vision of education for sustainable human development. In doing so, it positions schools as the primary social laboratories for lifelong resilience—the first and most enduring environment where coherence is learned.1,31

Integrative Synthesis: Education as a Salutogenic Enterprise or Conceptual Synthesis

Taken together, the reviewed literature demonstrates that the Salutogenic Model serves as both an explanatory and transformative theory for education. It transcends the long-standing divide between academic achievement and well-being, revealing that these are not competing aims but twin expressions of the same underlying condition—coherence. When individuals experience their world as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful, the very capacities that sustain mental health also sustain intellectual rigor, creativity, and moral maturity. Coherence thus becomes the invisible architecture of both learning and flourishing.15,16,22

In coherent educational systems, challenges are not minimized but metabolized—interpreted as catalysts for mastery rather than threats to security. Stress is not avoided but understood, framed as part of the developmental journey through which resilience and wisdom emerge. And meaning is not imposed but discovered, unfolding through relationships, reflection, and purposeful engagement. This orientation transforms schools from sites of compliance and performance into living laboratories of adaptation and growth—spaces where cognitive, emotional, and social learning intersect dynamically.9,21,29

The Salutogenic Model therefore redefines education as a health-generating process, not merely a knowledge-transmitting one. It positions teachers as facilitators of coherence, curriculum as a medium of meaning, and school culture as a web of relational resources that sustain manageability. Within such systems, academic excellence becomes a byproduct of psychological wholeness, and student resilience emerges not through pressure but through participation in coherent learning experiences.19,24

In this light, education becomes a salutogenic enterprise—a continual process of health creation, where knowledge, purpose, and connection converge to produce adaptive, engaged, and ethically grounded learners.40 The true measure of a successful school, therefore, cannot be confined to standardized test scores or institutional rankings. Rather, it lies in the enduring coherence it cultivates—the degree to which its students, teachers, and communities leave not only more informed but more integrated, capable of making sense of themselves and the world around them.55

Such schools do more than prepare individuals for external success; they build inner architecture—the capacity to find clarity amid complexity, resilience amid change, and meaning amid uncertainty.56 In nurturing coherence, they fulfill the deepest purpose of education: not to fill minds, but to form lives that can think, care, and thrive in the unfolding complexity of the 21st century.14

In this light, education becomes a salutogenic enterprise—a process of continual health creation where knowledge, purpose, and connection converge. The true measure of a successful school, therefore, is not only test scores but the enduring coherence it cultivates in its learners and educators.16,55 (Figure 3)

Critiques and Theoretical Limitations

While the Salutogenic Model has provided a powerful paradigm shift—from the study of disease to the study of health—it is not without theoretical and methodological limitations. These critiques are vital, as they ensure that the integration of salutogenesis into education, psychology, and preventive care remains both credible and contextually grounded.

1. Conceptual Ambiguity and Overgeneralization

A common critique centers on the conceptual breadth of the Sense of Coherence (SOC) construct. Antonovsky described SOC as a “global life orientation,”15 yet its very inclusiveness makes it difficult to operationalize precisely. Scholars have debated whether SOC is a stable trait, a dynamic state, or a multidimensional process.16,24 This ambiguity complicates empirical comparisons across populations and disciplines. In educational research, for instance, it remains unclear whether coherence reflects cognitive understanding of learning tasks, emotional regulation, or existential engagement—or all three simultaneously. Without greater conceptual precision, the model risks overextension.13

2. Measurement Challenges

Linked to this ambiguity are methodological limitations in measuring SOC. The most widely used instruments—such as Antonovsky’s SOC-13 and SOC-29 scales—were developed for adult populations and general health contexts.14 When applied to children, adolescents, or school systems, these tools often show inconsistent reliability and cultural sensitivity.26,29 Moreover, the reliance on self-report measures introduces social desirability and linguistic biases that obscure deeper cognitive and motivational mechanisms. Recent psychometric efforts, such as context-specific SOC scales for students,57 show promise but remain under-validated. Future research must refine these tools to capture the dynamic, developmental nature of coherence in learning environments.

3. Limited Attention to Structural and Cultural Inequities

Critics also argue that the Salutogenic Model, with its focus on individual sense-making, may understate the structural determinants of well-being—including poverty, discrimination, systemic injustice, and unequal educational access.40,58 In educational contexts, this can inadvertently place responsibility for adaptation on the student while minimizing the institutional forces that constrain manageability or meaning. For example, a learner’s ability to “make sense” of adversity is shaped not only by personal resilience but also by the fairness of grading systems, cultural inclusivity, and access to psychosocial support.56 Thus, a comprehensive salutogenic application must integrate socioecological and equity frameworks, ensuring that coherence-building is supported structurally and not demanded individually.

4. Overlap with Existing Theories

Another challenge involves the theoretical overlap between salutogenesis and related paradigms such as Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Positive Psychology, and Resilience Theory.12,25,59 While salutogenesis provides a unifying language—linking manageability, comprehensibility, and meaningfulness to motivation and adaptation—critics caution that this may blur theoretical boundaries rather than sharpen them. Empirical distinctions between constructs like “coherence,” “self-efficacy,” or “purpose in life” are often minimal.12,59 Future work should articulate how SOC functions uniquely—perhaps as a meta-construct integrating these overlapping mechanisms into a coherent framework of well-being.

5. Contextual and Cultural Limitations

The bulk of salutogenic research originates from European and Scandinavian contexts, where social welfare systems and educational equity are comparatively robust. Consequently, the model’s assumptions about resource accessibility, predictability, and autonomy may not generalize to societies with economic instability or collectivist cultural norms (Louw & du Plessis, 2022). In collectivist settings, for example, meaningfulness may derive more from community and spirituality than from individual agency. (11 13) Cross-cultural research is thus essential to validate how SOC manifests in diverse school environments, particularly in the Global South, where stressors and coping frameworks differ markedly.21

6. Integration vs. Dilution

As salutogenesis gains interdisciplinary traction, there is a risk of conceptual dilution—that “salutogenic” becomes a generic label for any positive or holistic practice.9 To remain scientifically meaningful, applications in education must retain the model’s theoretical integrity by grounding interventions in the triadic structure of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. Without this anchoring, salutogenesis risks losing its explanatory power and becoming merely rhetorical.15,55

Toward a Constructive Future

Addressing these limitations does not weaken the model—it enhances its applicability and theoretical robustness. Future research should:

-

Develop age-appropriate, culturally sensitive SOC measures for educational use.60

-

Integrate equity and systemic analysis into coherence-building interventions.9

-

Employ mixed-method longitudinal designs to explore how SOC develops across time and context.24

-

Articulate boundary definitions between SOC and adjacent constructs such as resilience, autonomy, and self-efficacy.12

By refining its precision while expanding its inclusivity, the Salutogenic Model can continue to evolve as a scientifically rigorous and ethically grounded framework for education and health promotion—one that acknowledges not only individual coping but also collective responsibility for creating coherent, just, and life-affirming systems.11

Transitional Synthesis

In summary, while the Salutogenic Model continues to offer profound insights into the processes that sustain health, learning, and human flourishing, its full potential in educational systems depends on ongoing refinement and contextual adaptation.7 The critiques outlined above do not diminish its value—they illuminate the pathways for strengthening its conceptual clarity, methodological rigor, and cultural inclusivity.16 As research continues to integrate salutogenesis with theories of motivation, resilience, and systems change, a new generation of scholarship is emerging—one that views education not merely as instruction, but as a coherent, health-generating ecosystem.21 The next step, therefore, lies in translating these theoretical insights into concrete practices, policies, and pedagogies that make coherence both measurable and livable in every school environment.56

CONCLUSION

The evidence synthesized in this review establishes that Antonovsky’s Salutogenic Model—originally conceived to explain how individuals remain healthy under stress—has profound implications for education.15 When transposed into the school context, salutogenesis reframes learning as a health-generating process, and schools as ecosystems for the cultivation of coherence, resilience, and lifelong adaptability.40 It invites a conceptual shift from “fixing problems” to “building resources,” recognizing that the same factors that sustain mental health also sustain motivation, engagement, and academic success.20

At its core, the Sense of Coherence (SOC) provides a powerful integrative construct for understanding how students and educators experience their environment.29 When school life is comprehensible (structured and predictable), manageable (supported by adequate resources), and meaningful (connected to purpose and belonging), stress becomes developmental rather than destructive.21 These conditions not only improve emotional stability but also enhance attention, persistence, and creativity—foundations of both learning and well-being.55 In this light, coherence emerges as the nexus of thriving, bridging the cognitive, behavioral, and social dimensions of educational success.13

The review’s findings also underscore that coherence is systemic, not merely personal. Teachers’ sense of coherence profoundly influences classroom climate, and coherent institutional leadership shapes how values, expectations, and relationships are lived out daily. Thus, salutogenesis offers a scalable model of transformation—from the mindset of individual learners to the culture of entire schools. It affirms that well-being and learning are not parallel goals but interdependent outcomes of coherent systems.16,21,55

Implications for Policy and Practice

Adopting a salutogenic perspective in education is not a superficial adjustment—it represents a paradigm reorientation in how schools, educators, and policymakers define, pursue, and measure success.55 Rather than centering on remediation, control, and performance metrics, a salutogenic approach views the educational enterprise as a living ecosystem for coherence-building—one that cultivates the psychological, social, and structural conditions for students and teachers to flourish. Translating this philosophy into practice demands transformation at four interconnected levels: curriculum, teacher formation, governance, and evaluation.

1. Curriculum Reform: From Knowledge Transmission to Meaning-Making

Traditional curricula often prioritize content mastery and standardized outcomes, assuming that information acquisition alone guarantees success. A salutogenic curriculum, by contrast, seeks to make learning meaningful, manageable, and comprehensible. This involves designing meaning-centered pedagogies that help students connect academic content with their lived experience, community context, and moral imagination.21,56

Project-based learning, service-learning, and interdisciplinary inquiry are especially powerful when framed through the lens of purpose and coherence. For example, linking science lessons to sustainability challenges or literature to social empathy transforms abstract knowledge into life relevance and contribution. This approach aligns with the OECD’s Learning Compass 2030,56 which defines future-ready education as “the capacity to navigate complexity through meaning-making, agency, and well-being.” In a salutogenic classroom, learning is not simply about knowing—it is about understanding one’s place in the world through knowledge.26

2. Teacher Development: Cultivating Coherence Leaders

Teachers are the carriers of coherence in the educational ecosystem.19 Their emotional stability, reflective capacity, and relational attunement profoundly influence students’ experiences of manageability and meaning. Hence, teacher education and professional development must move beyond technical pedagogy to include coherence training—equipping educators to nurture well-being within themselves and their students.40

This includes modules on reflective practice, emotional resilience, and participatory leadership, encouraging teachers to view their role as both facilitators of knowledge and architects of health. Professional programs should emphasize the interdependence between educator well-being and student flourishing, supported by research showing that teachers with high Sense of Coherence (SOC) demonstrate lower burnout, higher creativity, and greater student engagement.19,26,60

Institutionally, this means fostering professional communities of reflection and peer mentorship—environments where educators feel empowered, valued, and coherent.12In doing so, schools become centers not only of instruction but of psychological sustainability, where those who teach are themselves continually renewed.7

3. School Governance: Designing Coherent Institutions

At the structural level, school governance must embody the same coherence it seeks to instill in learners.16 This requires policies and leadership models grounded in transparency, equity, trust, and participation. Decision-making processes should be inclusive, ensuring that teachers, students, and parents experience agency and voice—conditions that directly enhance institutional manageability and meaning.9

A coherence-oriented policy framework promotes consistency between educational aims and organizational culture. This may include transparent communication systems, fair workload distribution, collaborative planning, and shared accountability. Research on health-promoting schools demonstrates that institutions characterized by participatory governance and relational trust produce measurable gains in well-being, academic achievement, and retention.31

Such governance transforms schools from hierarchical systems into learning communities, where leadership is distributed and coherence becomes a shared cultural value. The result is a sustainable model of school improvement—one that grows not through compliance but through collective coherence.30

4. Measurement and Evaluation: Expanding Indicators of Success

Finally, adopting a salutogenic paradigm necessitates a profound shift in how success is defined and measured. Traditional evaluation systems rely heavily on cognitive metrics—grades, test scores, and attendance—often neglecting the psychosocial conditions that make learning sustainable. A salutogenic framework calls for broadened indicators of educational quality that capture both academic and well-being dimensions.30,55,56

Assessment should therefore include measures of:

-

Sense of belonging (students’ perceived inclusion and connection),

-

Perceived control and manageability (students’ belief in their ability to influence outcomes), and

-

Purpose in learning (the motivational coherence linking effort to values and future goals).

Recent models such as the OECD’s Framework for Social and Emotional Skills and UNESCO’s Happy Schools Framework emphasize these same dimensions, underscoring their global relevance. Integrating psychosocial indicators into educational evaluation systems ensures that well-being is not peripheral but central to accountability.1,56 Over time, such data can inform targeted interventions, guide teacher training, and reshape policy priorities toward a culture of holistic success.11

Integrative Impact

Together, these reforms move education from an industrial model—focused on efficiency, standardization, and performance—to a salutogenic model—centered on coherence, meaning, and health creation. When policy and practice align in this way, schools become resilient systems capable of nurturing resilient individuals. The vision is not of schooling as preparation for life, but of schooling as life itself—a formative process through which young people learn not only to know but to be, belong, and become whole.56

These initiatives position schools as health-creating organizations, aligning with WHO’s Health-Promoting Schools model and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being). The salutogenic framework thus unites global education and health priorities within a single coherent paradigm.56,62

Directions for Future Research

The synthesis of Salutogenesis and education presents a fertile and largely untapped field for empirical exploration. While the conceptual foundations are robust, the evidence base remains uneven, particularly regarding how coherence develops, operates, and sustains well-being in educational systems across diverse contexts. 16, 28) Future research must therefore move beyond theoretical affirmation to applied, longitudinal, and cross-cultural investigations that reveal how coherence can be cultivated intentionally within real-world learning environments. The following directions highlight key areas for scholarly advancement.9

Longitudinal Development of Coherence Across Educational Stages

A major research priority involves understanding how the Sense of Coherence (SOC) evolves across different developmental and educational transitions—from early childhood through higher education. While existing studies affirm SOC’s stability in adults, far less is known about its plasticity in youth.26,57 Longitudinal designs could track how school experiences, relational climates, and pedagogical styles shape the formation and maintenance of coherence over time. Such data would clarify critical periods for intervention and reveal whether coherence can be systematically strengthened through curriculum design and mentorship.30

Intervention Research and Experimental Implementation

Beyond correlation, researchers must test intervention models that operationalize salutogenic principles in schools.22

Experimental or quasi-experimental studies could evaluate the effectiveness of coherence-building interventions—for instance,

-

Meaning-centered pedagogies

-

Reflective teacher training,

-

Peer support systems

-

Coherence-oriented school governance.19

Multi-level mixed-method designs (combining psychometric assessment, qualitative inquiry, and physiological stress indicators) would provide a holistic understanding of impact.29 These trials could help establish causal links between coherence, resilience, and measurable academic outcomes, offering an evidence base for policy adoption.56

Measurement Innovation and Psychometric Refinement

To advance methodological rigor, future research should prioritize the development of age-appropriate and context-sensitive SOC instruments. Traditional scales (SOC-13, SOC-29) often lack validity in younger populations or non-Western contexts.29,60 New tools should integrate cognitive, emotional, and behavioral indicators tailored for educational use—potentially combining self-report, teacher ratings, and observational measures.

Emerging technologies such as digital well-being analytics and AI-assisted sentiment mapping could further enhance the precision of coherence assessment, allowing for dynamic, real-time feedback in schools.56

Cross-Cultural and Socioecological Studies

A global research agenda must explore how coherence operates under varying cultural, economic, and institutional conditions.40 Most existing salutogenic studies are concentrated in European and Nordic contexts; however, educational realities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America present distinct stressors and coping mechanisms.9 Comparative cross-cultural studies could reveal how collectivist values, spiritual frameworks, or community-based education shape coherence differently from individualistic paradigms.58 This would strengthen the model’s cultural inclusivity and inform the development of localized coherence-building strategies aligned with indigenous pedagogies and social norms.

Integration with Neuroscience and Digital Learning Research

As digital learning environments expand, understanding how coherence manifests cognitively and neurologically is increasingly critical. Neuroeducational studies could investigate how comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness activate brain networks related to motivation, attention, and emotion regulation.62,63 Likewise, research on online and hybrid education should explore how digital design—interface clarity, interactivity, feedback loops—affects students’ sense of coherence in virtual settings. Such inquiries would bridge salutogenesis with 21st-century educational technologies, guiding the creation of coherence-enabling digital ecosystems.64

Teacher and Leadership Coherence as Systemic Variables

While student well-being remains central, teacher and leadership coherence are equally critical to sustainable change.19 Future studies should examine how educators’ SOC influences classroom climate, pedagogical style, and school culture. Investigating coherence as a systemic variable—rather than an individual trait—can uncover how coherence cascades through organizational hierarchies, shaping collective resilience. Participatory action research (PAR) could empower educators as co-researchers, ensuring that interventions reflect lived experience and foster professional agency.16,64

Policy Research and Translational Frameworks

Finally, scholars should focus on policy translation—how salutogenic evidence can inform decision-making at district, national, and international levels. Comparative policy analyses could evaluate how existing health-promoting school frameworks might be enhanced by explicit inclusion of coherence as a measurable construct.1,31 The development of Salutogenic School Accreditation Systems or Coherence Quality Indices could institutionalize coherence as a legitimate policy goal, moving it from theory into practice.56 Collaborations between universities, ministries of education, and global agencies will be essential to scale these innovations responsibly.65

Toward a Salutogenic Research Agenda

Future scholarship on Salutogenesis in Education must therefore be both rigorous and relational—scientifically grounded yet deeply human. The aim is not merely to measure coherence but to understand how it can be cultivated at scale: in classrooms, teacher training programs, and policy frameworks.40 By integrating insights from psychology, pedagogy, neuroscience, and sociology, a truly interdisciplinary field can emerge—one that sees learning as a health-creating process and education as a public health imperative.26

If pursued with precision and compassion, this research agenda holds the promise of transforming schools into systems that generate both knowledge and well-being, preparing not only capable learners but whole, resilient human beings equipped to sustain coherence in an uncertain world.62

Closing Reflection

The Salutogenic Model, when applied to education, restores to learning what is most essentially human — the search for meaning, mastery, and coherence in a complex and uncertain world.15 It redefines success not as the accumulation of knowledge or avoidance of failure, but as the ongoing capacity to interpret experience, mobilize resources, and find purpose amid challenge. In doing so, it invites educators, policymakers, and communities to reimagine schools as ecosystems of health creation, where the building of intellect and the building of wholeness are inseparable.40

At its heart, this paradigm recognizes that well-being and learning are not parallel pursuits but intertwined processes. The cognitive clarity of comprehensibility, the behavioral confidence of manageability, and the existential depth of meaningfulness together form the architecture of sustainable success — in school, and in life. When these dimensions align, both students and educators move beyond survival into flourishing; they experience education not as a system to be endured, but as a journey of coherence and growth.26

In an era defined by volatility, technological disruption, and social fragmentation, the Salutogenic Model offers more than a theory — it offers a philosophy of hope and direction. It reminds us that resilience is not merely endurance under pressure, but the art of transformation through meaning. It affirms that stress, when encountered with sufficient resources and clarity, is not an enemy but a teacher — one that can catalyze maturity, empathy, and innovation.31,59

For educators, this means reclaiming the moral and relational dimensions of teaching — to see every lesson as a moment of sense-making, every challenge as an opportunity to deepen coherence.19 For policymakers, it means designing systems that value belonging as much as performance, equity as much as excellence, and wholeness as much as achievement.56 And for researchers, it means advancing the science of coherence — not merely as an individual trait but as a collective, cultural capacity essential to the future of human development.11

Ultimately, the vision of a salutogenic education is not utopian; it is deeply practical. It begins with a single premise — that health, meaning, and learning are created in the same place: in the hearts and minds of people who experience their world as understandable, manageable, and worthwhile. When this coherence becomes the organizing principle of education, schools cease to be institutions of preparation for life and become laboratories of life itself — places where students learn not only to think, but to live well.16,56

In this light, the future of education and the future of health are one and the same endeavor: to build societies capable of coherence in the face of complexity, compassion in the face of change, and creativity in the face of uncertainty.65,66 Such is the promise of a Salutogenic Education — a vision not merely of surviving in the world as it is, but of shaping the world as it ought to be.14

Acknowledgement

Portions of this paper—including editing, organization, and refinement of figures and references—were developed with the assistance of an AI language model (ChatGPT). All interpretations, final decisions, and substantive scholarly contributions are the author’s own.

I would like to thank Dr. Allan Brester for his cursory editing and advice.