Introduction

As the U.S. population ages along with populations worldwide, the incidence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) including disorders affecting muscles, bones, joints, tendons, or ligaments is also increasing. Chronic pain is a primary symptom of MSDs and is the main contributor to disability worldwide with MSDs affecting 20–33% of the world’s population.1 Between 1990 and 2017 the incidence of MSDs increased globally by 58% from 211 million to 334 million individuals affected.2 MSDs affect more than one out of every two persons in the United States age 18 and over, and nearly three out of four individuals age 65 and over.3 Trauma, back pain, and arthritis are the three most common MSDs reported and are the most common reasons individuals visit a primary care provider, an emergency department, or a hospital each year. The rate of MSDs is much greater than the rates of circulatory diseases and respiratory diseases, which affect about one in three people. Chronic MSDs are conditions that last more than 12 weeks, including chronic neck or back pain or chronic upper limb disorders, rheumatic diseases, and degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis or osteoporosis.4

Chiropractic and physical rehabilitation alone or in conjunction with surgical or pharmacological therapies are commonly prescribed to treat MSDs.5 The aims of chiropractic and physical rehabilitation when treating MSD are to reduce pain, disability, injury recurrence, and improve function resulting in improving the patients’ quality of life.6 A recent review of clinical trials concluded that chiropractic care seems to be more effective than pharmacological nonsurgical interventions for low back pain in reducing pain, increasing range of motion in lumbar spine, reducing disability status, and enhancing general health.7 Other authors have reported similar benefits of chiropractic care in reducing pain and disability associated with MSDs.8,9 Similarly, several literature reviews have indicated that physical rehabilitation is effective in treating chronic pain due to MSDs.10,11 Both the American College of Rheumatology and the Arthritis Foundation recommend physical therapies for the management of pain and disability related to osteoarthritis effecting the hands, hips and knees.12 Thus, both chiropractic and physical rehabilitation have been demonstrated to be effective in treating MSD-related pain and disability.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound and lasting impact by changing some components of face-to-face chiropractic and physical rehabilitation care to telehealth or digital health platforms.13 More recently, evidence is emerging to support the efficacy of chiropractic and physical rehabilitation being administered through telehealth platforms, or digital health, for conditions such as osteoarthritis, low-back pain, and rehabilitation prior to and following hip and knee replacement.14,15 Digital health according to the World Health Organization, is the field of knowledge and practice associated with the development and use of digital technologies to improve health.16 Other authors have determined that digital health can promote patient engagement in health care and plays an important role in improving health outcomes in patients with MSDs.17 A common limitation of both chiropractic and physical rehabilitation being administered in person or through digital health is the efficacy of the care plan is dependent upon the patient adhering with the prescribed plan of care. Prescribed care plans for MSD by chiropractic and physical therapist commonly includes at home exercises and attending prescribed clinic visits. A recent study indicated that only 44% of MSD patients reported following prescribed at-home exercises.18 Other investigators reported adherence with at-home exercise and clinic visits for chiropractic and physical therapy to be highly variable, ranging from 15–87% for clinical visits and 15-70% for completing prescribed at-home exercises.19,20 A more recent study reported that only 43% of MSD patients completed a prescribed exercise rehabilitation program to the point of being discharged by their provider.21 Previous investigators estimate that between 14% and 70% of patients who have been prescribed physical rehabilitation do not complete their prescribed course of care or discharge themselves (self-discharge) from care.22,23 These low rates of adherence with prescribed chiropractic and physical rehabilitation are not meaningfully higher when the care plan is administered via digital health.14,24,25 In a previous study, the authors reported that 51% of the usual care group were self-discharged compared to 54% of the group receiving a digital health intervention.26 These authors also reported the greater number of clinic visits among the patients who adopted the digital health intervention and appeared to generate more clinic charges and payments.26 Finally, no other studies have compared the revenue generated by patients attending a chiropractic and physical rehabilitation clinic who did and did not choose to adopt a phone-based app to complement their care. These studies indicate that a persistent challenge to treating MSD patients’ whether face-to-face or through digital health is the patient’s low levels of adherence with the prescribed care plan and high likelihood of not completing their prescribed care and self-discharging themselves.

The objective of this study was to compare the number of appointments kept, and the revenue generated, among patients attending a chiropractic and physical rehabilitation clinic who did and did not choose to adopt a phone-based App (EMBODI) to complement their treatment. A secondary purpose was to determine if the number of appointments kept, and the revenue generated, were different among patients who were self-discharged versus doctor-discharged and did or did not adopt the App. These purposes were addressed through testing the following 3 hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 states: Patients attending a chiropractic and rehabilitation clinic who adopted a phone-based App (EMBODI) will have more appointments kept, and more revenue generated from treatment than patients who did not choose to adopt the App. The second hypothesis is: Among patients who were doctor-discharged those who adopted the App will have more appointments kept, and more revenue generated from treatment than patients who were doctor-discharged but did not adopt the App. The third hypothesis tested in this study is: Among patients who were self-discharged those who adopted the App will have more appointments kept, and more revenue generated from treatment than patients who were self-discharged but did not adopt the App.

Methods

Design

A retrospective analysis of all new outpatient electronic medical records at a multisite chiropractic and physical rehabilitation practice were evaluated between January 1, 2023 to December 31, 2024. Beginning in January 1, 2023, all new adult patients aged 18 years and older admitted to this practice, were offered the opportunity to download a phone-based App, EMBODI, to complement their care plan. Over the course of the study these clinics employed a total of 5 licensed chiropractors with physical therapy privileges. The new patients who downloaded and registered on the phone-based App self-selected into the App User group. Patients who chose not to download and register on the App self-selected into the No App User group. All eligible patients included in the study had their electronic medical record accessed to determine if they prematurely terminated treatment against the advice of the provider (self-discharged) or if they completed their prescribed treatment (doctor-discharged). Also extracted from each patient’s electronic medical record was the number of appointments kept, and the revenue generated by treating the patient. This resulted in a quasi-experimental 4-group (App User vs No App User & doctor-discharged vs self-discharged) design in which the medical records of all eligible patients initially presenting for treatment between January 1, 2023 to December 31, 2024 were reviewed and if eligible, included in the analysis.

Sample

The electronic medical records of new patients who were scheduled for care during January 1, 2023 to December 31, 2024 at four community-based clinics that provided chiropractic and physical rehabilitation care services in the greater Washington D.C. area were initially screened to be included in this study. Patients were excluded from the sample if they were less than 18 years of age, never began a care plan, had an unknown discharge status on their medical record, or a remaining balance for clinical services. These clinics specialize in treating pain and increasing functional ability. Of the 2,378 patients included in the analysis 1,851 (78%) patients were in the App User group and 527 (22%) were in the No App User group. These participants were also classified as doctor-discharged (n=1,042, 44%) or self-discharged (n=1,336, 56%). During their initial visit, patients seeking care who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria after January 1, 2023 were informed they could download a free mobile App to their phone that they could use to compliment the care they were receiving in the clinic. At this initial visit, all patients were told about the components of the App, shown an example of the App features and the reward structure as a result of using the App. Patients were also told use of the App was voluntary and would in no way affect their care or relationship with their provider or the clinical agency.

Ethical Considerations

This record review study was approved by the Sport & Spine Rehab Clinical Research Foundation (SSRCRF) IRB #SSR.2024.2 which included waivers for informed consent and HIPAA requirements. This IRB has been established within SSRCRF is to support research projects conducted by clinical researcher not affiliated with a university-based IRB. It is registered with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) within the Department of Health and Human Services (OHRP/HHS) and has pledged, via the Federal Wide Assurance, (FWA) to follow federal rules for protecting human subjects in all of its research. Members of the SSRCRF IRB have completed human subjects protection training offered online through the for Human Research Protections and Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program). All data extracted from the electronic medical records were de-identified, compiled without patient identifiers and were kept secure and confidential. No compensation was provided for any subjects involved in the study.

Procedure

During the initial visit to one of the targeted clinics each patient completed an initial assessment with a provider who prescribed a plan of care which included home exercises and a series of follow up clinic visits. After January 1, 2023 these providers were not blind to the patient’s decision to download and register on the phone-based EMBODI App. The plan of care prescribed by the provider included the number and frequency of the follow up clinic visits which was individualized to the type and severity of the patient’s condition. The number of treatment sessions was initially determined by the provider and based upon the patient’s clinical progress and other factors may have been reduced or extended during their care plan. When the provider prescribed a plan of care the patients were informed that their account would be charged $25 if they did not attend future scheduled visits without giving notice (“no show”) or did not contact the clinic to cancel the appointment within 24 hours of the appointment.

Once patients self-selected into the App User group and registered on this App they were asked to describe their personal goals for care (e.g. decrease pain, increase functioning) and why this goal was important to them (e.g. “so I can play with my grandkids”). Also, during this registration process the patient committed to a time during the day when they would perform their prescribed exercises. This registration process incorporated the behavioral change constructs of control over personal goal setting and aimed to increase the patient’s perceived benefits of engaging in the care plan by linking engaging in the care plan with progress toward their personal goal and with something that the patient valued. This registration process was also designed to increase the individual’s self-efficacy by allowing them to control the time when they would engage in the prescribed exercise and requesting, they formally commit to completing the exercises at the time they have chosen. Following registration, the EMBODI App then provided brief video clips of 3-9 exercises that were selected by the patient’s provider to address their specific condition and are consistent with their initial ability. The patient could perform his or her exercises “with” the provider in the pre-recorded video which is designed to build self-efficacy and social support. The App asked the patient to “check” that they had completed or “skipped” each prescribed exercise. After completing the exercise session, a positive feedback message was transmitted (e.g. “You did all of your exercises. Your dedication to your home exercises makes all the difference on your journey to recover.”). Then the patient provided a rating of their progress and feedback regarding how challenging the exercises were. This information was processed by the EMBODI App to modify and personalize the patient’s future exercise sessions and provided the patient with individualized control over their exercise sessions. Following this documentation more positive feedback was transmitted over the App in order to build future commitment to adhere to the prescribed exercises (e.g. “You did it! Come back tomorrow to continue making progress on your journey to recovery.”). The EMBODI App also allowed the patient to see a graphic depiction of their adherence over the duration of their prescribed care plan, send a message to their provider with a response within 24 hours and schedule future in-person appointments in the clinic. Again, these components of EMBODI were designed to increase the patient’s perceptions of control, self-efficacy, facilitating the patient-provider relationship, and provide positive feedback. Finally, the EMBODI App provided electronic “badges” when the patient achieved critical milestones to positively reinforce needed behaviors. The platform also provided an automated reward when a patient achieved specific clinical milestones in their care plan that could be redeemed for iOIG compliant incentives. This feature is compliant with the Office of the Inspector General offering an item as a reward that is valued fifteen dollars or less.

Outcome Variables

The electronic medical records of all eligible patients who were initially seen in the targeted clinics were reviewed during the 4-month period after their initial assessment. Based on the discharge summary documentation on the patient’s medical record, patients were classified as completing prescribed care plan and being discharged by their provider (doctor-discharged) or not completing their prescribed care plan and self-discharging themselves (self-discharged). Also, extracted from each patient’s electronic medical record were the number of appointments kept and the revenue generated by treating the patient.

Analysis Plan

Data were extracted from the medical records of all patients identified to be eligible for the study and transcribed into a SPSS v28.0 database. These data were validated to include only eligible patients. Eligible patients were initially grouped into the App User Group and the No App User groups. Chi square statistics for homogeneity were calculated to compare these 2 groups on gender and discharge status. Independent t-tests were calculated to compare these 2 groups on age, the number of appointments kept, and the revenue generated. Factorial 2x2 ANOVAs were calculated to determine the main effects of type of discharge (doctor vs self), App use (App User vs No App user), and the interaction of these factors on the outcomes of appointment kept and revenue generated. Significant main effects (P <.05) of these ANOVA equations indicated post hoc comparisons of the group means using Tukey’s least significant differences.

Results

A total of 2,378 unique patient records were included in the analysis. Table 1 compares the 1,851 (78%) patients who self-selected the App User group with the 527 (22%) patients who self-selected the No App User group. These participants were also classified as doctor-discharged (n=1,042, 44%) or self-discharged (n=1,336, 56%). Chi square analysis revealed that the App User group had a statistically greater proportion of patients being doctor-discharged (80%) compared to the proportion of patients in the No App User group who were doctor discharged (76%). T-test analysis indicated that App User group was significantly younger (40.57 + 12.06) than the No App User group (43.77 + 14.26). This analysis also revealed that the App User group had significantly more appointments kept (9.76 + 7.42 vs. 7.21 + 6.82) and generated more revenue ($1,362 + 1,459 vs. $1,193 + 1,553) when compared to the No App User group.

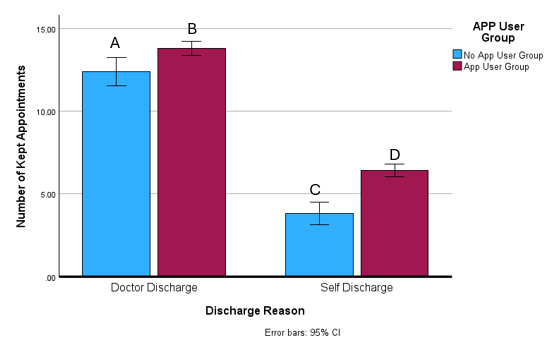

The factorial 2x2 ANOVA revealed a significant interaction (f = 3.60, P = .05) of type of discharge and App use on number of appoints kept. Post hoc analysis indicated significant (P < .00) differences between all four types of discharge by App use group means. Figure 2 displays the average number of appointments kept among these groups with the No App User-Self-discharge group keeping 3.81 + 4.06 appointments, followed by the App User-Self-discharge group keeping 6.43 + 5.93 appointments, then No App User-Doctor-discharge group keeping 12.39 + 6.91 appointments and App User-Doctor-discharge group keeping 13.82 + 7.03 appointments.

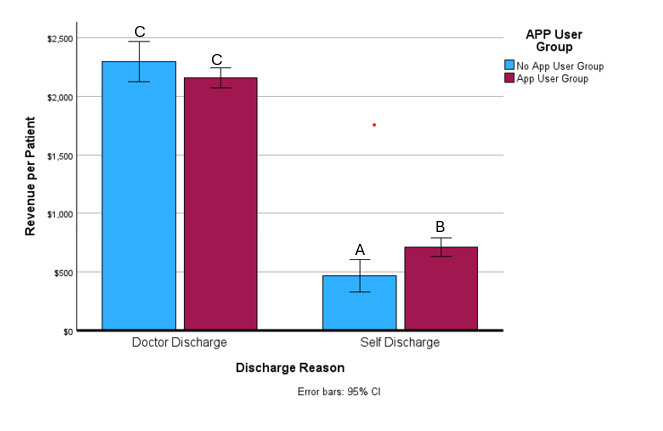

Similarly, the factorial 2x2 ANOVA revealed a significant interaction (f = 9.71, P = .00) of type of discharge and App use on the amount of revenue generated per patient. Post hoc analysis indicated significant differences (P < .00) between three of the four group means. Figure 1 displays the average revenue generated per patient among the four groups. The No App User-Self-discharge group generated significantly lower revenue than the other 3 groups ($465 + 567). The patients in the App User-Self-discharge group generated significantly less than both of the Doctor-discharge groups ($711 + 771) but significantly more than the No App User-Self-discharge group. Patients in the No App User-Doctor-discharge group ($2,299 + 1890) and App User-Doctor-discharge group generated similar (P = .15) amounts of revenue per patient ($2,158 + 1,689) and more revenue than either Self-discharge group.

Discussion

The findings support the first hypothesis by demonstrating that patients who self-selected to download the EMBODI App, kept an average of 2.55 more appointments and generated an average of $170 in additional revenue from treatment than patients who did not choose to download the App. As well, the findings partially support the second hypothesis. Figures 1 and 2 indicates that within doctor discharge group the patients who downloaded the EMBODI App kept more appointments (on average 1.5 more appointments) although generated similar amounts of revenue ($2,299) compared to the doctor discharge group who did not download the App ($2,158). The third hypothesis was supported by the finding that among patients who self-discharged, those who downloaded the App kept an average of 2.6 more appointments and generated $246 in additional revenue than the patients who were self-discharged and did not download the App. These findings indicate that the EMBODI App contributed to significantly more appointments kept among patients who were self-discharged or doctor-discharged and greater revenue among patients who were self-discharged from a chiropractic and physical rehabilitation clinic. The EMBODI App did not affect the revenue generated among patients who were doctor-discharged.

Although these findings support a majority of the study hypotheses, they merit further consideration. Since patients self-selected to or not to download the App there is no way to distinguish if their greater adherence with their prescribed clinic visits and higher levels of revenue generation could be solely attributed to the App or some other characteristic that predisposed them to downloading the App and being more adherent to their care plan. Although the No App User group was statistically older than the App User group, this 3-year difference may not have been clinically important enough to explain the differences in clinic visits or revenue generation different between these groups. Among patients who self-discharged, downloading the App appeared to contribute to a greater number of clinic appointments kept and greater revenue generated during their treatment compared to self-discharged patients who did not download the app. This indicates that the App may have increased adherence and revenue among patients who eventually did not complete their prescribed care plan. This pattern of the EMBODI App contributing to more clinic appointments kept was also observed among the patients who were doctor-discharged. Patients in this group who downloaded the App exhibited significantly greater appointments kept but similar revenue generated than patients who were doctor-discharged who did not download the App. This finding that the App appeared to increase appointments and not revenue among patients who were doctor-discharged may be attributable to a number of factors. First, being doctor-discharged from care may not be based solely on achieving specific therapeutic goals. On occasion, patients are doctor-discharged from care because the provider and/or the patient do not perceive benefits of the care plan or the patient has achieved a plateau in their recovery. Being doctor-discharged from care may also be attributed to the patient’s psychological state including depression, anxiety, or fear of pain limiting their ability or willingness to participate in the care plan, leading to discharge. Finally, difficulty in attending clinic appointments or inadequate access or feedback from the provider may contribute to a patient being doctor-discharged from care.

The EMBODI app was designed to address factors previously identified as contributing MSD patients not adhering to their prescribed care plan including accessibility issues, and patient perceptions of a lack of clinical progress in resolving pain or improving functioning.21 The literature indicates that behavior change theory-based interventions are effective in changing health behavior in the laboratory and ‘real world’ clinical settings.27,28 These theory-based interventions including graded tasks, goal setting, self-monitoring, problem solving and feedback from the provider significantly enhanced adherence to prescribed physical rehabilitation care plans among patients with chronic MSDs.29,30 Other studies have indicated that theoretical constructs including health locus of contro l,20 self-efficacy31,32 perceived benefits of the care plan,33 facilitating the patient-provider relationship, and providing positive feedback,34 are correlated with increased adherence with prescribed care plan among patients with MSDs. Many of the commercially available chiropractic and physical rehabilitation digital health apps emphasize education about the MSDs and prescribed exercises but are devoid of theoretical constructs that contribute to changing health behavior The EMBODI app facilitated the theoretical behavioral constructs of increasing perceived control, self-efficacy, perceived benefits, facilitating the patient-provider relationship and providing positive feedback.28,35 These components of the App are supported by the literature,20,31–34 and may have contributed to increased adherence and more revenue generation among the self-discharge group who downloaded the App and to a lesser extent to the Doctor-discharge group who downloaded the App.

The findings of this study are also consistent with 2 preliminary studies, in which we compared patients attending a physical health clinic who did and did not choose to adopt a preliminary version of the phone-based App to complement their care.26,36 This early version of the App employed the cognitive behavioral change technique of reward incentive gamification to encourage adherence to prescribed clinic appointments. In these studies, the patients who adopted the phone-based app had a greater number of kept appointments, were less likely to self-discharge, and generated more revenue for the clinic compared to the usual care group. A limitation of these preliminary studies is the digital health Apps incorporated only gamification and no other behavioral change constructs.

This study contains a number of limitations and strengths that may direct future inquiry in this area. The validity of this study is strengthened by the large sample size collected over multiple clinical sites and the use of the electronic medical record as the source of the outcome variables. The data employed in the analysis is also clinically valid because the revenue generated was extracted from the electronic medical record. Although encouraging, these findings must be interpreted cautiously due to a number of methodological limitations. First, the source of the data for this study was a retrospective review of the electronic medical record. Although a rich source of data, the electronic medical record is limited by the consistency and expertise of individuals entering data into the system and missing data that is not easily reconstructed.37 The second limitation in this study was patients self-selected to or not to download the EMBODI app. This decision to self-select to adopt this mobile App may have been made by patients who were more likely to attend more clinic visits and generate more revenue or by patients with lower disease acuity or with conditions less expensive to treat. Future studies may wish to randomly assign patients who are initially willing to download the App to groups who are and are not provided with the App to minimize the impact of this potential self-selection bias. The large sample examined for this study increased the external validity of the findings, although this large sample also increased the likelihood of detecting statistical significance of a small effect size.

CONCLUSION

These findings support the association between adopting the EMBODI App and increased adherence with clinic appointments and greater revenue generation particularly among patients who self-discharge. Future investigators need to employ more rigorous methods to explore which behavioral change constructs included as components of the EMBODI App have the greatest impact on increasing patient adherence with care and indicators of clinical progress. Clinicians will need to consider the benefits of deploying the EMBODI App in all or a portion of their patients against the cost and staff involvement in managing this App.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Greenstein and Ms. Etnoyer-Slaski are employees of the Kaizo Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Greenstein is CEO of the Kaizo Health Clinics but is not involved in patient management. The EMBODI App was developed by Kaizenovation Tech, LLC and commercially available through www.embodihealth.com.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request."