INTRODUCTION

Phantom limb pain is a chronic, debilitating condition affecting approximately 64% of individuals with lower extremity amputations, significantly impairing quality of life.1,2 PLP is perceived as pain in the non-existent limb and is thought to result from maladaptive neural plasticity, involving peripheral nerve sensitization, spinal cord hyperexcitability, and cortical reorganization.3,4

Amputations most commonly result from complications from advanced peripheral vascular disease, particularly among individuals with diabetes mellitus, who often present with comorbid conditions contributing to limb loss.5 Traumatic injuries, particularly from combat-related incidents such as land mines and explosive devices also account for a substantial proportion of limb amputations, especially among young adults.6

Interestingly, research indicates that the etiology of amputation may influence the prevalence and severity of PLP.7 Traumatic amputations are frequently linked to greater pre-amputation pain and higher distress, which are known to predict a higher incidence and severity of PLP compared to amputations caused by vascular or diabetic conditions. Conversely, individuals undergoing elective amputations for chronic vascular disease may experience less severe PLP, possibly due to prolonged pre-amputation pain leading to gradual cortical adaptation.8

A wide range of treatment options exist for managing PLP, including pharmacologic therapies such as gabapentin, amitriptyline, tricyclic antidepressants, opioids, and ketamine, as well as non-pharmacologic approaches including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), transcranial magnetic stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, prosthetic use and training, hypnosis, acupuncture, and mirror therapy. However, these treatments often yield inconsistent results, and there remains limited high-quality evidence supporting the effectiveness of non-pharmacologic interventions.9,10

Chiropractic care is widely utilized for LBP and radicular symptoms, using many means of spinal manipulation and soft-tissue therapies to improve function and alleviate pain.11,12 While chiropractic interventions are well-documented for musculoskeletal conditions, it is underexplored for neuropathic pain, such as PLP.13,14 This case report describes an unexpected improvement in PLP in a patient treated for chronic LBP and radicular symptoms with automated lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release, suggesting a potential novel role for the use of long-axis distraction and myofascial release in the treatment of patients co-presenting with low back pain and PLP.

Case Report

Patient Presentation

A 66-year-old male sought care for evaluation and treatment of chronic LBP and left radicular pain into the residual limb. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, right toe amputation, chronic renal disease, diabetic ulcers, right Charcot neuroarthropathy surgeries, simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplant, left transmetatarsal amputation, and end-stage renal disease. PLP, described as burning and stabbing sensations radiating into the absent left foot, began 2 days post-amputation in 2020. The reported aggravating factors were standing, walking, and sleeping, with partial relief from pain medications. Prior treatments included physical therapy and epidural steroid injections (L4-L5, L5-S1) with limited relief.

Examination

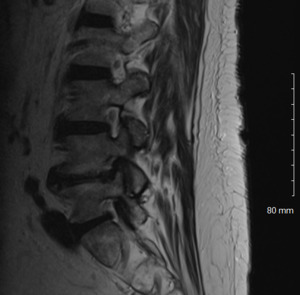

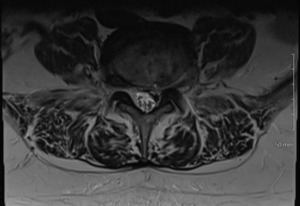

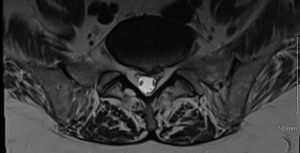

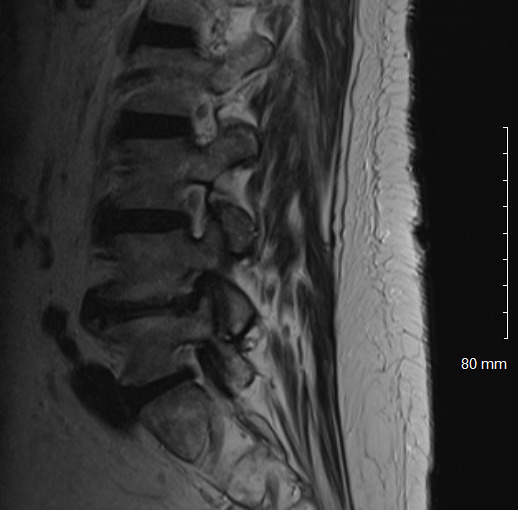

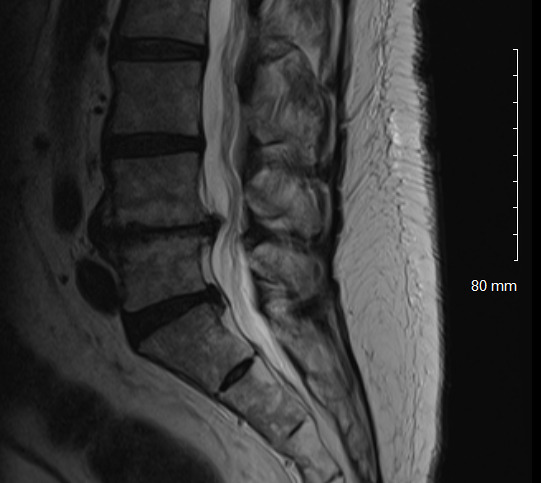

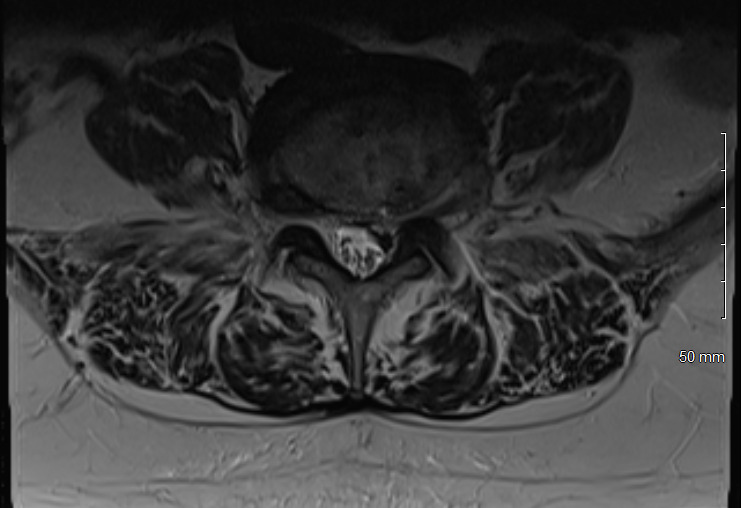

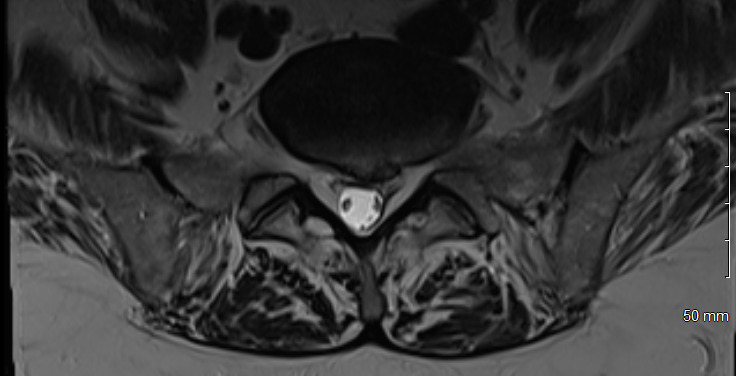

Physical examination revealed hypertonicity and tenderness in the lumbar paraspinal muscles and the left posterior hip region. He reported a pain level of 8/10 on the NPRS, reflecting both LBP and radicular symptoms. Additionally, a score of 32 out of 40 on the DVPRS indicated substantial pain-related functional impairment. A 2024 lumbar spine MRI demonstrated degenerative disc disease, arthropathy, severe left subarticular recess stenosis at L4-L5 with L5 nerve impingement, and a small left central disc extrusion at L5-S1 abutting the S1 nerve root (Figs. 1–4).

Intervention

The patient underwent a treatment plan of automated lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release over 6 visits in 3 weeks. Myofascial release was applied to the lumbar paraspinal and left posterior hip musculature with the goal of reducing muscle tension, improving tissue mobility, and addressing active myofascial trigger points contributing to pain and dysfunction. Techniques included sustained pressure and slow, deep strokes along the muscle fibers to release fascial restrictions and improve circulation. This was followed by automated long-axis distraction using a mechanical table to gently decompress the lumbar spine, aiming to reduce nerve root irritation and improve joint spacing. The combination of these interventions was selected to address both local musculoskeletal pain and referred radicular symptoms.

Outcomes

At discharge (Visit 6), NPRS improved from 8/10 to 4/10, and DVPRS score improved from 32/40 to 18/40. The patient discontinued care due to insurance limitations. During a follow-up period, 6 visits over 2 months, the patient experienced improved LBP and function but no sustained PLP relief. He was subsequently internally referred to interventional pain management for further evaluation and treatment.

Outcomes were assessed using NPRS and DVPRS scores, with visit-by-visit details as follows (Table 1):

Discussion

This case report documents an unexpected improvement in PLP during chiropractic treatment for LBP and radicular symptoms in a patient with a below-knee amputation. The temporary abolition of PLP reported at Visit 5, which was sustained for 2 weeks, suggests that automated lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release may influence the neuropathic pain pathways in amputee patients. Furthermore, lumbar distraction may reduce mechanical compression on the L5 nerve root, as seen on MRI (Figs. 1-4), potentially decreasing spinal cord hyperexcitability associated with PLP.15 Myofascial release, by addressing trigger points and muscle tension, may alter afferent input to the spinal cord, influencing pain processing.16 Chiropractic manipulation has been shown to modulate pain perception and widespread pressure sensitivity, likely through activation of descending inhibitory pathways. While these mechanisms may play a role in conditions involving central sensitization, their relevance to neuropathic pain such as PLP needs further investigation.17

The correlation between PLP severity and LBP and radicular symptoms, noted by the patient, suggests shared neural pathways, possibly involving the lumbosacral nerve roots or spinal cord integration. Previous studies on PLP management have focused on mirror therapy, TENS, and pharmacotherapy, with limited exploration of manual therapies.9,18 The efficacy of chiropractic care for LBP and radicular symptoms is well-supported. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide moderate-to-high quality evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating that spinal manipulation is associated with clinically meaningful improvements in pain and function. This level of evidence supports spinal manipulation as a viable treatment option, though further research may help refine its role across broader patient populations.11,14 This case substantiates these findings, suggesting a potential overlap in mechanisms for neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain in patients living with amputations.

Although not conclusive, the patient’s positive response to treatment may offer valuable insights for chiropractors treating patients with PLP. Given the complexity and treatment resistance often associated with PLP, this case highlights potential considerations for managing patients living with amputations. Non-pharmacologic interventions are increasingly emphasized due to the limited and inconsistent effectiveness of medications, particularly in patients where pharmacologic risks may be elevated as is in this case with comorbid diabetes and renal disease.19 Chiropractic care, as a low-risk intervention, could be integrated into multidisciplinary protocols for amputees, complementing therapies like mirror therapy or physical therapy.

Future research is warranted to investigate the mechanisms of lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release on PLP. Randomized controlled trials could evaluate the efficacy of chiropractic care for PLP, comparing it to standard interventions like mirror therapy or TENS. Integrating chiropractors into collaborative care models for amputee patients may offer complementary support in managing musculoskeletal pain and improving functional outcomes. While further research is needed, such interdisciplinary approaches could enhance overall patient care for PLP.

Limitations

As a single case report, these findings cannot establish causality or generalization to other patients. The improvement in PLP may have been coincidental or influenced by non-specific factors such as placebo effect or natural symptom variability. Limited follow-up and potential confounders, including changes in activity, prosthetic fit, or psychosocial factors, may also have contributed to symptom changes. Controlled studies are needed to determine whether chiropractic care directly impacts PLP.

Conclusion

This case highlights an unexpected improvement in PLP during chiropractic treatment with automated lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release for LBP and radicular symptoms. The decrease in NPRS and DVPRS scores, alongside 2 weeks of PLP relief, suggests a potential relationship between LBP, PLP and lumbar long-axis distraction and myofascial release. These findings suggest that lower back conditions may contribute to PLP and should be considered during evaluation.

Consent For Publication

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.