Introduction

Covid-19 surfaced in December 2019 and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March of 2020.1 This virus had a 3% fatality rate, varying on location1 and age. Many governments created travel restrictions and shutdown businesses to decrease the spread of the virus, which clearly impacted including doctoral training programs.2 These shutdowns further impacted higher learning by causing pedagogical methodologies to move toward distance learning.2

According to the Chiropractic Educator’s Research Forum, many chiropractic doctorate programs had to modify their approaches to teaching and testing within weeks to respond to the pandemic.3 Some chiropractic instructors at my institution created virtual classrooms, voice-over-PowerPoints (Microsoft, Redwood, WA), videos, video assignments, online formative quizzes, online summative quizzes, and online summative exams. Other models available included massively open online courses (MOOCs), recorded classes, online live interaction, tutorial, short communications, and conferences.4 Many of these models can be accessed by computer, tablet4 or smartphone.5 Advantages of online and blended learning include transcending space and time, convenience, equal or slightly more effectiveness for learning, and reusability.6 However, meta-analysis examining effectiveness in learning has shown high heterogeneity7 and thus should be treated with caution.6 Disadvantages include high cost of preparation, maintenance costs, platform maintenance and learners’ feeling of isolation.6 Bajpai recommended considering the learning theory being employed to develop a course with online component to fit the intended outcomes.8 According to Carmargo, the Covid-19 pandemic “had a catalytic effect on the change in educational processes worldwide.”4

Basic Life Support (BLS) is taught in many chiropractic colleges at the healthcare provider level according to the American Heart Association or American Red Cross protocols.9 BLS includes skills such as rescue breathing, conscious choking, unconscious choking, CPR 1 rescuer, CPR 2 rescuer and AED. In addition, a general approach to scenario management called the initial Assessment is taught. The initial assessment is detailed in Table 1 from an amalgamation of American Red Cross protocols.9 This initial assessment is modified depending upon the victim’s age (adult, child or infant). These skills and victim types result in 18 possible scenarios. Learning these critical skills by healthcare providers improves the recovery from cardiac arrest; among other maladies.10 Compared to the burden that cardiac arrest imposes there has only been modest gains in survivability attributed to system optimization rather than improvements in treatment that require skill training.10 Assessment of these skills are often performed by objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE)11 where a rubric is scored while the student performs procedures in a simulated clinical scenario.

Many teaching methods have been investigated in the past. Nord found that web-based CPR training had no significant effect on practical CPR skills, although this was on 13-years-old and thus cannot be applied to the target population of my study (adult graduate students).12 Bylow gave evidence that web-based training improved adults’ ability to perform BLS skills.13 Systematic reviews comparing difference methods of training where limited by low methodological quality studies and low n numbers: n=514 and n=11.15 An RCT by Moon and Hyun suggested that a blended (in class and online) approach seemed to improve knowledge using a 20-point practical performance rubric.16 The blended approach with virtual patients was studied with pediatric life support as well with positive results in skill performance.17 Garcia-Suarez’s systematic review supports this generally.15 The primary aim of this study was to determine if there was any difference in BLS OSCE grades between different phases of Covid-19 and related modifications to teaching and evaluation.

My question was to see if the new changes to the course made any difference in the BLS OSCE grades. This study was conducted retrospectively to determine how the Covid-19 pandemic affected learning of basic life support (BLS) in the 9th quarter of a chiropractic doctoral program that lasts 13 quarters by comparing the BLS OSCE scores per Covid-19 phase. The phases of Covid-19 where based upon the mandates from the State. Phase 0 is a term that I chose for pre-Covid or minimally affected time period including 6 quarters. Phase 1 was the time frame of maximal impact from Covid-19, where only essential business were open. Phase 2 included minimal business shutdown (restaurants at 50% capacity, bars closed, large gatherings discouraged). In addition, social distancing, mask usage and hand washing was highly encouraged. Many businesses made these recommendations mandatory. Different phases of Covid-19 required different teaching and testing methods, which are detailed in the methods and summarized in Table 2.

Methods

IRB Determinations

This study did not constitute human subjects research pursuant to 45 CFR 46. This study was assigned a non-human subjects assurance number, for tracking purposes only, which is N2020-11-19-M.

Teaching and Assessment Methods for Phase of Covid-19:

The phase 0 group was prior to Covid-19 and consisted of 6 consecutive quarters. The students’ experienced conventional teaching methods including lecture of 20-minute duration, limited video (whatever they could find on the internet themselves), PowerPoint presentations and mainly 30 minutes of guided training through week 7 of 11. Around week 7, the students completed an in-class written test. The scheduling of these OSCEs were accelerated due to the looming pandemic shutdowns, with the last term in the 6-term sequence. Weeks 7-9 were designated for in-class OSCEs. Week 10 was for retakes. Week 11 was final exam week.

The phase 1 group was totally online (one quarter). They learned by online videos through Utube (Google) from the American Red Cross9 and videos specifically made by me that were organized by weeks inthe Brightspace learning management system (LMS). Also, online virtual classrooms that emphasized the main points of the videos were performed during even weeks to provide students time to watch the material. Two summative online quizzes were created for the midterm and Week 6 or 7 before the OSCEs. Weeks 7-10 were OSCE weeks. I gave instructions about how to access the virtual classroom, where to find their appointment time and to position themselves 10 feet from the camera. More weeks were necessary to accommodate for technical issues, such as too much light from a window, student too close or too far away, video or audio not working and connectivity to virtual classroom. The virtual classrooms for the OSCEs were set every 10 minutes. A few students went over the time, which affected subsequent virtual classroom preset time allocations. I had to use MS Teams for a few students since they could not figure out how to get their audio or video to work in the Brightspace virtual classrooms. Make-up sessions were offered the following quarter for hands-on experience with Covid-19 modifications: washing hands prior to signing in with designated partners, manikin cleaning before usage, saying “breath” instead of breathing into manikins, social distancing except with optional designated partner (otherwise alone), manikin cleaning after session, and washing hands.

The phase 2 group (one quarter) learning was analogous to the Phase 1 group with the following modifications. Optional in-class sessions during odd weeks 3,5, and 7 were implemented with simultaneous virtual classroom. Some students had to stay home for various reasons related to Covid. OSCEs were performed in-class. These activities used Covid-19 modifications.

OSCE Assessment Methods

BLS OSCEs are practical exams where the student performs a scripted protocol on a scenario. Scenarios were randomized assigned using Excel. Students began the OSCE not knowing their assigned scenario and discovered what their scenario was as it developed. Students were graded using the rubric in Table 3, which is modified from American Red Cross protocol.9 Student were allotted approximately 10 minutes; however, those who went beyond this limit were penalized in rare situations under category 24 called “Other” (for stalling and moments of confusion).

Statistical Methods

Retrospective analysis of anonymized BLS OSCE grades was performed by grouping them by Covid phase, checking assumptions and determining whether the best analysis approach would be ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test set at alpha of 0.05 with equal parsing. Planned comparisons between all group combinations using familywise error rates would be determined if the test was significant. This analysis would be performed using the statistics platform R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A large Phase 0 group was used to represent normal to avoid comparison to a single cohort effect. However, the other phases might show cohort effects.

Background literature acquisition methods included the following searches in Pubmed: Covid-19, CPR, online; Covid-19 online; CPR online; cardiopulmonary resuscitation web (filtered for free-full text). Ten articles identified from literature review. The search also included sources from my personal collection regarding BLS protocols and statistics. Additional literature acquisition by Pubmed was performed after peer review using the following terms: online learning, teaching and learning, and online educational assessment.

Results

Descriptive statistics reveal means and standard deviations that were rather similar (Table 4). Notice that phase 0 has an n number of 404, representing 6 quarters.

Assumptions check revealed that all categories of phase had significant non-normal distributions as per Shapiro-Wilk’s test, although, Shapiro-Wilk’s test becomes too sensitive when N numbers are higher. Levene’s test was insignificant for heterogeneity of variance. Phases were independent since they were different students. Phases were also independent in the sense that they did not affect each other since no one had to retake the class. Group sizes were quite different (404, 44, 73).

The inferential statistic ANOVA revealed p-values greater than alpha and therefore not significant (Table 5). For difference of means significance tests (like ANOVA) the sampling distribution should be normal in the groups.18 The n numbers are above 30 and therefore the central limit theorem can be invoked for the sampling distribution and thus it can be considered normal.19 However, because of the extreme differences in group sizes, a non-parametric test was determined to be necessary. Since these were independent groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test18 was performed and revealed no significance (Table 5). The null hypothesis was not rejected. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to reject the idea that the different teaching and testing methods did not make a difference.

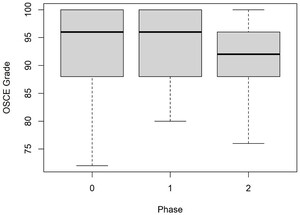

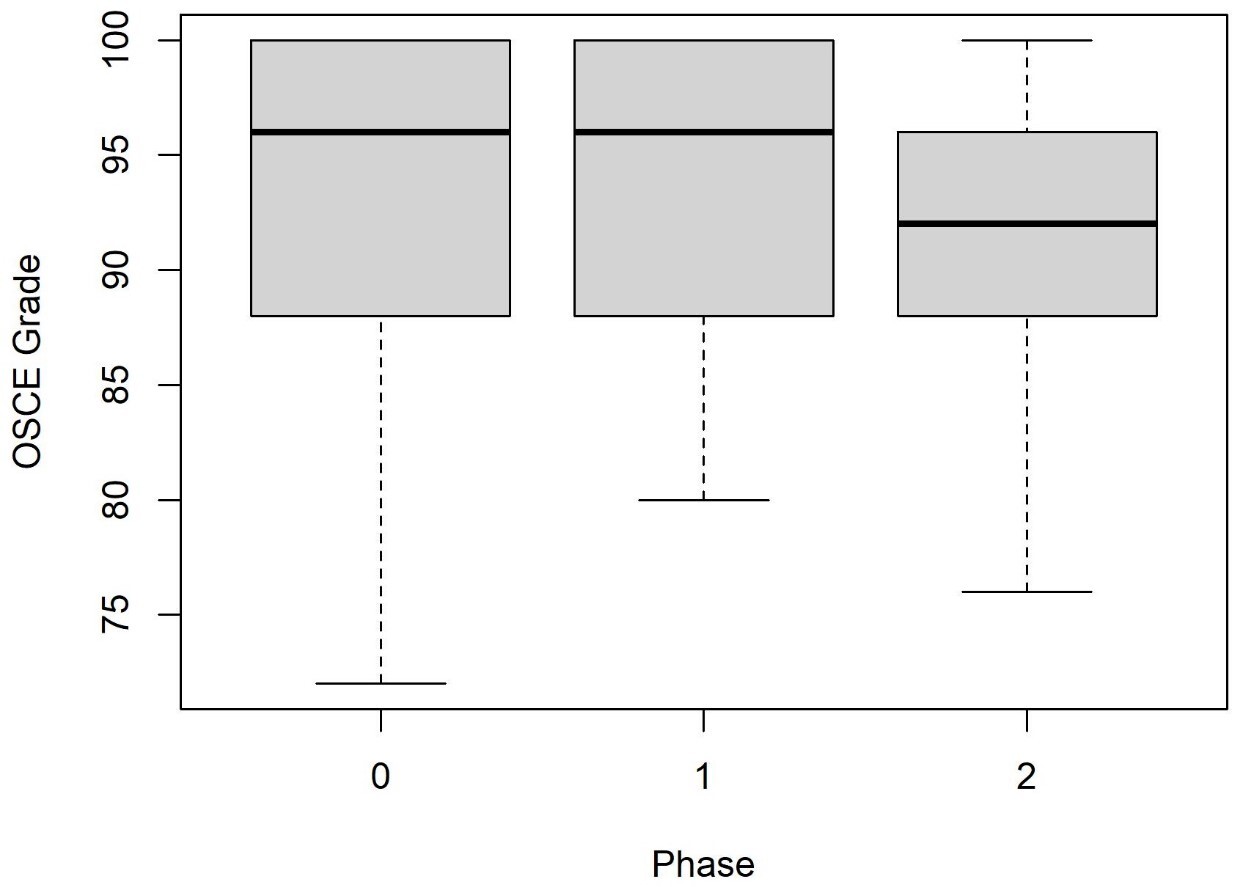

Graphical analysis illustrated the general lack of difference between the sample groups in a tight range. Although the Phase 3 median appeared slightly lower, the effect size was small and there was significant overlap of the distributions (Figure 1). Therefore, analysis by estimation (effect size and confidence interval) revealed only a slight insignificant decrease of grades in phase 2.20

When the term means are plotted against the grades (Figure 3), there does not seem to be a seasonal pattern affect. Notice that the last number in the term number corresponds to the seasons: 1 = Winter, 2 = Spring, 3 = Summer, 4 = Fall. The first two numbers are the last two digits of the year. For example, the 18 of 184 represents 2018 while the 4 means that this term is in the fall.

Discussion

Overview

Just as practicing chiropractors have required adaptation to the challenges caused by shutdowns related to the Covid-19 Pandemic,1 pedagogical changes in some chiropractic colleges have been attempted to overcome these challenges. This discussion will review the results of this attempt to overcome these challenges, difficulties of online assessment and limitations of this study.

Interpretation of Results

Covid-19 did not seem to affect CPR OSCE grades to a level of statistical significance as per ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis. This could be interpreted in many ways. Was there a seasonal affect? Did one factor undo the effect of another? For example, did the students use prompters that elevated their grade that was depressed by the hard time they went through during that time? Or perhaps none of the factors made a significant impact. These other factors would have to be explored through prospective studies including linear regression and model building. Regarding the possibility that the low, high, medium is a seasonal affect, it does not seem to be the case as noted in the results.

Difficulties

Difficulties could have affected scores and the implementation of the study methods. Some difficulties I experienced in performing BLS OSCEs online included concern regarding cheating, manikin availability, student positioning and technical glitches. Cheating could be accomplished by having a person behind the camera giving prompts or having written notes around or behind the screen. This concern was not solved during these OSCEs. Manikins were not available in many instances and therefore dolls, scarecrows (stuffed full body nylon suits) or pillows where used. Positional concerns involved telling the student to move back far enough to see from the top of their head to the manikin. This often took some time in a limited time allocation. Written instructions were given prior to the OSCE, yet the students often had too many intricacies in their lives to manage during the pandemic. Technical problems where the students could not get the virtual classroom or video camera to work did occur. This caused some sessions to extend beyond the limited time allocation of 10 minutes, which then affected other’s OSCE times. Khalaf et al reports some technical issues during their online high-stakes written exam.2 Kakadia discussed the use of breakout rooms through platforms like Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA) to decrease technical issues from skill-specific station switching.11 Other difficulties include multiple limitations in this study that cause generalizability to be affected.

Limitations

Limitations included video influences, unknown GPA influences, our retrospective design, stress influences, ceiling affect and prompting affect. The availability of general access online videos on the internet prior to Phase 1 might have caused the effect of videos to be decreased, although the new videos created in response to Covid-19 were very specific, including the details of the initial assessment. Effects were not corrected by GPA influences. The influence of stress was not reported. This study was performed by retrospective design and therefore was not optimal. Influence of stress was not able to be determined retrospectively. A possible ceiling affect was accentuated since the students had to retake any OSCEs with a grade less than 80%.

CONCLUSION

Further studies should consider limitations of this study and provide a plan to eliminate or capture any main effects or interactions.Comparison of different OSCEs in different contexts may be helpful. Other contexts could include chiropractic adjustment set-ups, venipuncture, first aid (bleeding, stroke, etc.), physical examinations (abdominal exam, examination of the thorax), and vitals sign examination. Determining areas most missed would be helpful for students while preparing for OSCEs in advance.

Covid-19 impacted the United States economy and its educational system. Adaptations had to be created rapidly to provide equitable educational services. Covid-19 modifications that included online teaching, video availability and online testing did not seem to affect CPR OSCE grades significantly. Many possibilities exist in interpreting this lack of difference. Perhaps the student’s learning did not suffer, or the student just had to work harder. Limitations should be considered with the design of future research efforts.