Introduction

Electronic health records (EHRs) allow comprehensive consolidation of patient medical data into digital files that can be accessed in real time to help improve patient management and communication between providers.1 EHRs are a vital part of health information technology, containing large aggregates of longitudinal patient information such as medical history, test results, medications, chart notes and clinical codes.

Healthcare systems regularly use administrative codes to classify diagnoses of patients seen and healthcare services delivered to those patients. Internationally recognized coding schemas such as Current Procedural Terminology® (CPT®) codes and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (IDC-10) codes are used to identify services and diagnoses respectively.2 In the last decade, such coding data stored in EHRs have been routinely harvested for large-scale analysis to assess system performance and quality of care3 despite various degrees of reported inaccuracy and incompleteness.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has utilized an EHR for decades and much has been published on VHA EHR data,5 providing an ideal setting to study EHR accuracy in various user populations in VHA. Particularly, since VHA began including chiropractic services in 2004, it has offered a unique opportunity to explore the use of EHRs by chiropractors in the largest integrated hospital system in the US.6 To the best of our knowledge, agreement between EHR coding and provider report of chiropractic visits has not been reported. The purpose of this study is to compare VHA chiropractors’ self-reports of the most common conditions seen and services provided with national EHR data from VHA chiropractic visits.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of VA administrative data for all on-station chiropractic visits from fiscal year (FY) 2019 (October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019). This date range was selected to coincide with the timeframe of the previous VHA Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) provider survey described below. This was a program analysis project using the VHA Chiropractic Program Office’s operational data dashboard. Data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Chiropractic visits were identified based on any visit to a clinic coded as a chiropractic clinic, defined by VHA stop code 436 in either the primary or secondary position. All ICD-10 and CPT® codes associated with a chiropractic visit in FY 2019 were extracted, and the top 100 most frequently used of each were tabulated (Table 1). We collapsed these into representative categories for comparison, and calculated the proportion of codes falling into each category.

Additionally, we conducted a secondary analysis of data from a previous VA chiropractor survey to calculate relative frequencies of provider-reported diagnoses and procedures. This survey captured responses in a 5-item categorical scale of several per day, several per week, several per month, several per year, and never. We created a framework to translate these categorical responses to relative frequencies by assigning numerical converter values ranging from 4 to zero in descending order from most to least frequent. We then multiplied the number of survey responses for any given category by the numeric converter. The resulting values were then summed for each ICD-10 and CPT® survey question. This was applied to survey responses for conditions seen and treatments delivered.

Results

We identified 66,666 unique patients who received 301,739 on-station chiropractic visits during the study timeframe.

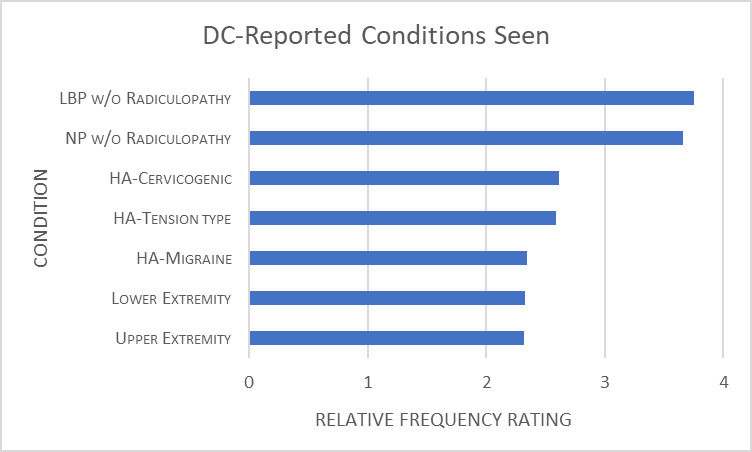

The top 100 ICD-10 codes for these visits encompassed 94.05% of all ICD-10 codes in FY 2019. These were collapsed into 9 categories, presented in Figure 1. The most frequent diagnoses were LBPwo (47.7%) followed by NPwo (20%). The results of our analysis of provider survey responses to conditions seen are presented in Figure 2. The most common conditions from provider self-report were also LBPwo and NPwo.

The top 100 CPT® codes accounted for 99.96% of all procedural conde in FY2019. We collapsed these into 9 categories, presented in Figure 3. The most common procedures were CMT (42.7%) and manual therapy procedures (13.9%). The results of our analysis of provider survey responses regarding services provided are presented in Figure 4. The most common therapies from provider self-report were CMT and therapeutic exercise. The survey did not measure E&M services.

Discussion

This work presents a preliminary analysis of chiropractic clinical coding and provider self-reported practice characteristics in the largest US integrated healthcare system.

LBPwo was the most frequent ICD-10 code in administrative data (47.7%) and was also rated the most common condition seen by provider self-report (3.75/4 relative frequency). The frequency of ICD-10 codes for NPwo (19.99%) was less than half of that for LBPwo, yet DCs’ self-reported NPwo relative frequency (3.66/4) was essentially the same as LBPwo. Even greater disparity existed between the very low frequencies of ICD codes for headache and extremity conditions, and the relatively higher rates at which DCs report seeing these conditions. A scoping review by Beliveau of worldwide chiropractic utilization found the most common reasons for chiropractic care were LBP (49.7%), NP (22.5%), extremity conditions (10.0%), and headaches (5.5%), with these proportions being most consistent with the EHR data from our study and not provider self-report.7 Our EHR data is also largely consistent with prior reports of conditions seen by VA chiropractors.6

The most frequent CPT® code grouping in administrative data was CMT, representing 42.7% of all CPT® codes. This was concordant with DC self-report placing CMT at the highest relative frequency rating of 3.86/4. This is also consistent with chiropractic practice worldwide, with CMT being the most frequent service provided.7 DCs reported providing therapeutic exercise, self-management, and patient education at relatively high frequencies, yet CPT® codes for these therapies were very rare. The proportions of therapeutic codes presented in this study are similar to prior reports of services provided by VA chiropractors.6 Our work demonstrates use of Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes was common, but we could not assess provider self-report of E&M services since these were not included in the DC survey.

The discrepancy demonstrated between chiropractors’ coding and self-report of conditions seen and treatments delivered is not surprising, as other studies have demonstrated disagreement in other healthcare disciplines.4,8 A study looking at whether a goals of care discussion occurred during a clinic visit found considerable disagreement between patient report, clinician report, and EHR documentation.9 In this study, of the 3 methods evaluated, only patient-report of the occurrence of a discussion was associated with patient-reported receipt of goal-concordant care. Though our study does not allow direct assessment of whether EHR or provider self-report more accurately represents VHA chiropractic patient visit characteristics, a previous study of pain-related primary care encounters found that documentation of pain care procedures in EHRs significantly underrepresented the actual pain management delivered by physicians during office visits.8

Despite well-documented inaccuracy, EHR data continues to be used for healthcare research and quality of care assessment. A project looking at 150 randomly selected MEDLINE-cited administrative database research studies which used diagnostic or procedural codes as key study variables, sought to measure the proportion of the studies which accounted for coding accuracy. The study concluded that diagnostic and procedural codes were commonly used but infrequently validated, and furthermore, subjects in administrative data studies with a code frequently did not have the condition it represents.10

Nevertheless, administrators and researchers are increasingly using VHA EHR data to examine system performance, pain management practices, and quality of care. This may be because EHR contains aggregate information on a large sample of individuals which allow stakeholders to evaluate outcomes across a wider range of settings, geographical region, and patients.5 It has also been reported, that the use of EHR data for research may be less expensive and time consuming, as well as reduce the potential for participant risk and burnout.5 However if EHR data are demonstrated to be inaccurate or incomplete, inferences made regarding healthcare delivery based on such data may be limited. It was beyond the scope of our study to measure whether clinical coding or provider self-report is more accurate. Further assessment is needed to determine if VHA chiropractor coding accurately reflects clinical practice.

Limitations

There are limitations to our work as EHR data are subject to variations in provider use of clinical coding. Additionally, we analyzed ICD-10 and CPT® codes for all VHA chiropractic visits, and did not attempt to assess codes assigned to the patient visits of the chiropractors who completed the DC survey. We used an untested process to calculate relative frequencies of diagnoses and procedures reported in a prior DC survey. Other studies have used direct observation and patient and provider interviews at points of care as a means of assessing what occurred during patient visits.1,4 Little is known about how these three approaches compare to each other and previous studies suggest significant differences regarding provider and patient report of what occurred during visits.9,11 Although direct observation via audio or video-recording patient encounters may be the most transparent method, it is also invasive and resource-consuming.12 Future work should include a more rigorous assessment of patient visit characteristics, including patient and/or provider interviews at the point of care, for comparison with EHR coding.

Conclusion

This study describes areas of concordance and divergence between VHA chiropractor self-report of practice characteristics and EHR clinical coding data. Given the significance of EHR documentation to patient management, interdisciplinary team communication, and allocation of health resources, discrepancies between actual care and EHR data may have negative impacts. Additional work is needed to better understand VA chiropractor clinical coding and its impact on patient and system outcomes.

_without.png)

_without.png)