INTRODUCTION

Though it incurs $18.5 billion dollars per year in healthcare costs, sarcopenia is a commonly overlooked and undertreated clinical condition in primary health care settings.1 Sarcopenia is a serious condition putting older adults at increased risk for falls, fractures, head injuries, mobility impairments, loss of independence, decreased quality of life and co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.2–6 Unmitigated, sarcopenia more than doubles the likelihood of death.7 As portal-of-entry health care providers, chiropractors may play an essential role in fulfilling this "unmet clinical need’ and providing aid to patients at risk for, or already experiencing this potentially devastating condition. This paper reviews the literature on this overlooked condition.

DISCUSSION

I searched PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus and Google Scholar to identify relevant papers published between 1980-2021 using search terms sarcopenia, frailty, muscle wasting, older adults, aging disorders, muscle, strength and function loss.

Papers were screened according to the following eligibility criteria: adults aged 50 and older in community dwelling or institutionalized settings; men and women screened for sarcopenia with clear diagnostic criteria; outcome measures related to sarcopenia, including strength, muscle mass and physical or functional performance. Study designs included systematic review, and meta-analyses. I limited the search to English language, human adults. The main reasons for exclusion were papers with younger participants or not including sarcopenia’s effect on related outcomes. Of 1,121 records retrieved, 38 papers were included in this review. These papers covered the causes, consequences, prevalence, risk factors, deficits and natural history of sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia comes from the Greek language “sarco-” meaning flesh, “penia,” loss, and sarcopenia “loss of flesh.” The word was first coined by Dr. Irwin Rosenberg, who used the term to describe age-related declines among the elderly.8 Sarcopenia has been defined by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) as “a syndrome characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength with a risk of adverse outcomes such as physical disability, poor quality of life and death.”9

Disease of Sarcopenia

In recognition of a need, in 2016, an ICD-10 code was authorized for sarcopenia, establishing it as a disease entity.10

ICD-10-CM Code M62.84

Sarcopenia: Progressive decline in muscle mass due to aging which results in decreased functional capacity of muscles.

Code Classification

-

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99)

-

Disorders of muscles (M60-M63)

-

Other disorders of muscle (M62)

Diagnostic Related Groups

- Tendonitis, Myositis, Bursitis

In establishing sarcopenia as a disease, it was thought physicians would become more attuned to this condition; however, this has not been shown to be true, since sarcopenia is still commonly overlooked and undertreated in primary health care settings.1

Consequences

The consequences of sarcopenia range from simple inconveniences to life-threatening events in the latter stages of the condition. There are 2 principal consequences:

-

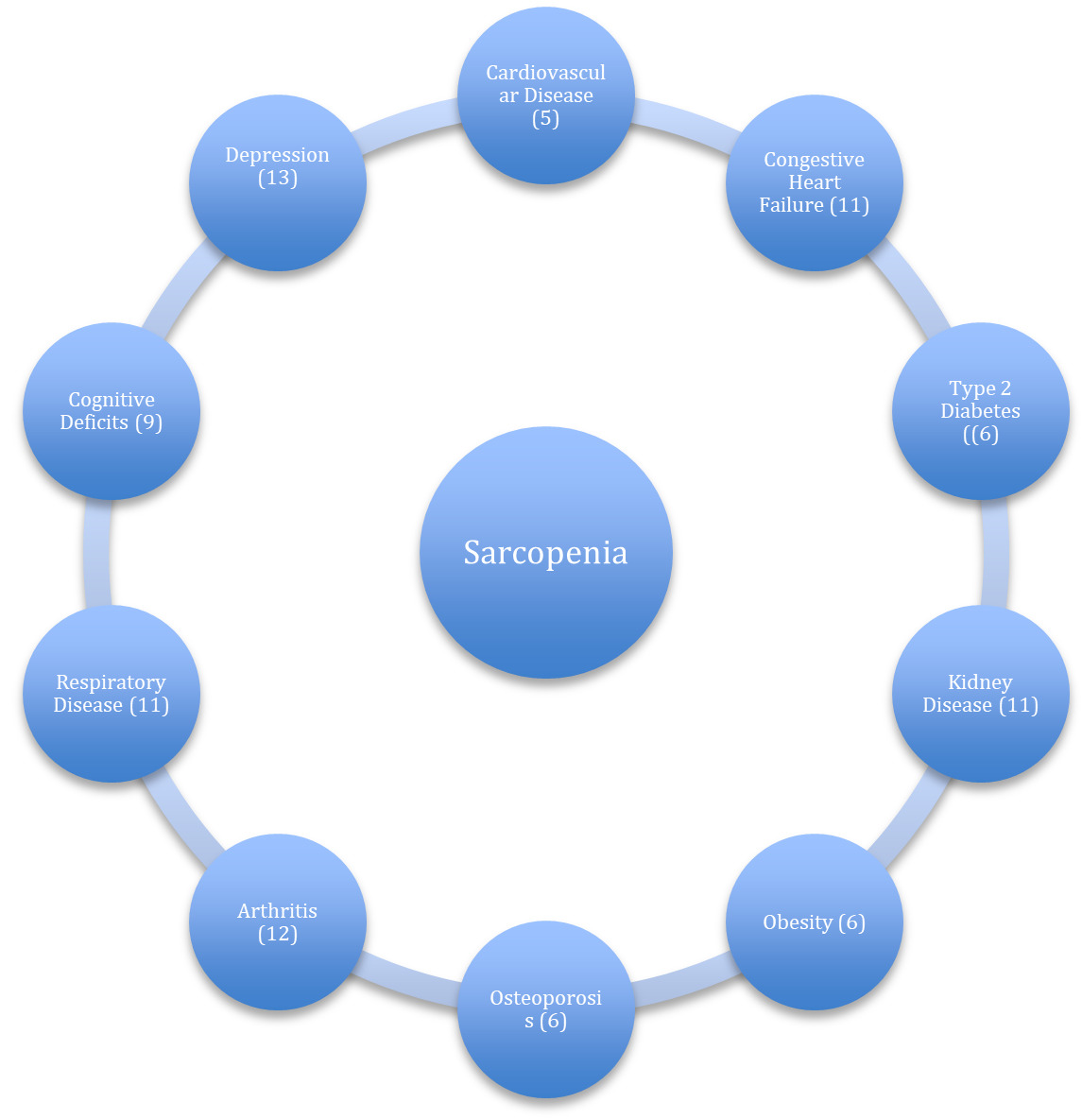

Increased risk of co-morbidities (Figure 1), which increases the risk of chronic disease and death.

-

Increased risk of physical disability and diminished function, which reduces quality of life, robs one of independence and increases the risk of mortality.

Due in part to the increased risk of co-morbidities associated with it and other risk factors independent of co-morbidities, sarcopenia increases the likelihood of death. A 2011 study of 1413 subjects aged 74.4 years found those in the lower quartile (25%) for fat-free mass experienced significantly greater mortality rates.14 A 2012 study of 70-year-old individuals

with sarcopenia found their risk of death was 2.34 times greater than non-sarcopenic adults.7 A study15 following community-dwelling older adults over an extended period found the median survival time for sarcopenic individuals was 10.3 years and 16.3 years for adults not experiencing sarcopenia.

Physical Disability

Functional capacity reflects the ability to perform normal activities of daily living including bathing, dressing, rising from a bed or chair, climbing stairs, carrying groceries etc. When an individual loses the ability to perform these most fundamental of activities, we refer to them as being physically disabled. Physical disability is associated with decreased quality of life, loss of independence, increased likelihood of institutionalization and increased risk of death.3 As an independent risk factor, the probability of developing physical disability is greater in individuals with sarcopenia3 Older adults with severe sarcopenia are 2-5 times more likely to display physical disability than adults with normal muscle mass.3 People of age, especially those experiencing sarcopenia, are more vulnerable to physical capacity loss. These losses not only magnify sarcopenia but increase the likelihood of other consequences.

Health Burden

Sarcopenia is a primary threat to public health and the financial burden it places on individuals and the U.S. health care system is significant. Although there is limited data on the economic impact sarcopenia has, estimates of direct health care costs related to it are $18.5 billion dollars a year. Percent of total U.S. health care costs attributed to sarcopenia have been set at 1.5%. Additional expenditures for those diagnosed with sarcopenia have been calculated at $860-$933 per year.16

Prevalence

Sarcopenia has been shown to exist across numerous age groups and settings (Table 1).

Deficits

Consistent with its clinical definition, the principal deficits associated with sarcopenia are muscle, strength, and function loss. These deficits not only alert us to the probability of sarcopenia, but unaddressed heighten its consequences. Following are the muscle, strength and functional losses seen with aging and sarcopenia.

Muscle Deficit

For most adults, the quantity and quality of muscle tissue begins diminishing in the fourth decade and accelerates in the fifth and sixth decade and beyond.12 In some instances, however, this decline may begin as early as the third decade.21 Between 50 and 80 years of age muscle is typically lost at the rate of .5-1.5% per year.2 By the age of 80 the typical adult has lost 50% of their muscle mass.2 Some key muscles are more vulnerable to losses with aging. For instance, the quadricep muscle has been shown to be diminished by 40% in older adults by the age of 60. This loss increases the risk of mobility impediments by 34-45% and risk of hip fractures by 50-60% independent of bone density.12,22 Rapid muscle loss is particularly threatening to older individuals. Demling found 10, 30 and 50% loss of lean muscle mass in acutely hospitalized older patients was accompanied by an identical increase in mortality and risk of death.23

Strength Deficit

Another red flag for sarcopenia is strength loss which can be dramatic with aging. Strength loss in middle age is estimated at the rate of 2-4% per year.24 This loss exceeds the rate of muscle loss by three times25 making strength loss a better indicator for early sarcopenic change. Loss of strength with aging also demonstrates steep decline after the age of 60.26 Over one’s life, independent of disabling injuries, strength is typically diminished by 45% in men and 50% in women.27 These losses increase the likelihood of sarcopenia.

Function Deficit

Functional deficits are the third of the principal hallmarks that lie at the base of sarcopenia. Functional capacity, including the ability to perform normal activities of daily living, typically diminishes 3% per year beginning at 60 in sarcopenic adults.6 Adults with diminished function have an elevated incidence of disability.28 Sarcopenic adults lose an estimated 30% of functional ability by the age of 75. This loss increases the likelihood of disability by 2-5 times29 and elevates the risk of falls and mortality.7

Risk Factors For Sarcopenia (Figure 2)

Poor Nutritional Habits

Malnourishment and malnutrition marked by inadequate nutrient intake are also regarded as major contributing factors to sarcopenia. Older adults demonstrate malnourishment and malnutrition across several different settings which increases the risk of sarcopenia. Kaiser30 found the per cent of older adults experiencing malnourishment and at risk for malnutrition in a hospital setting was 86%. The same measure in a nursing home was found to be 67% and 38% in a community health setting. Meaning 1 in 3 independently living older adults may be malnourished or at risk for malnutrition.

Studies of patients experiencing sarcopenia also demonstrate pervasive nutrient deficits. The PROVIDE Study of sarcopenic adults 65 years of age and older found 33% demonstrated lower vitamin D; 22% reduced vitamin B12, and 2-6% diminished magnesium, phosphorous and selenium than non-sarcopenic adults.31 Another study32 found sarcopenic adults demonstrated widespread nutrient deficits, including 10-18% shortfall of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Folic Acid, Magnesium, Vitamin B6 and Vitamin E.

A phenomenon, which many older adults experience, called the anorexia of aging (Figure 3) personifies the challenges aging individuals have in maintaining effective nutritional habits. And the risk this imposes on the development of sarcopenia.

Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity significantly increases the risk of developing sarcopenia. Sedentary behavior diminishes muscle protein synthesis markedly contributing to muscle and function loss.21 Even short-term inactivity can result in muscle loss, as studies show active adults who become inactive have a greater likelihood of developing sarcopenia.

Immobilization

Following an injury or re-aggravation of a pre-existing condition many individuals immobilize themselves, even engaging in “bed rest” for fear of aggravating their condition. Immobilization, which may be viewed as a deeper expression of inactivity, can decimate function, strength and muscle mass. Dirks found 5 days of immobilization resulted in a 4% loss of quadricep mass and 9% reduction in strength in young, healthy subjects.33 A study performed with older adults (68 yrs.) discovered 10 days of bed rest resulted in a 7% loss of muscle mass.34 Even short-term reductions in daily movement activities has been shown to reduce lower body muscle mass in healthy adults by 2.8%.35

Obesity

Obesity in all age groups including older individuals has emerged as another factor contributing to sarcopenia. Obesity in aging adults stimulates sarcopenia by altering lipid metabolism and fostering insulin resistance and inflammatory pathways.36 Increased secretion of leptin from adipose tissue up-regulates inflammatory cytokines resulting in muscle wasting and fraility in older men. Fraility is a debilitating condition closely paralleling sarcopenia and extending beyond it. Both obesity and sarcopenia are independent causes of disability, mobidity and mortality. Together they increase the risk of adverse health outcomes in older adults.37

Smoking

Smoking fosters sarcopenia by decreasing muscle mass and increasing abdominal fat. Smokers possess lower appendicular muscle mass than non-smokers. And those who’ve smoked the most demonstrate the lowest muscle mass. Metabolites of smoking accelerate muscle wasting by increasing oxidative stress and catabolism and inhibiting anabolism. Smoking may also negatively affect muscle preservation by increasing muscle protein breakdown and inhibiting muscle protein synthesis.38

Stages of Sarcopenia

In 2018, a consortium of experts known as the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) published a consensus document describing the stages of sarcopenia (Table 2).

Sarcopenia staging is a valuable process that aids in the clinical assessment and management of the condition. Identifying a patient’s stage is important for setting outcome goals and selecting interventions that may be useful. Sarcopenic individuals can best be supported with early detection. However, evidence indicates even those with severe sarcopenia can recover muscle, strength and function with effective intervention.

CONCLUSION

Sarcopenia, defined as the accelerated loss of strength, muscle mass and function with aging, is a growing public health threat with significant personal and societal implications. Unmitigated sarcopenia increases the risks of falls, fractures, head injuries, mobility impairments, loss of independence, decreased quality of life and increased risk of death. Sarcopenia has also been linked to numerous co-morbidities underscoring it’s significance as a public health issue. Estimates indicate 33% of adults over the age of 65 experience sarcopenia. Despite this, sarcopenia is commonly overlooked and under treated in primary health care settings. With a better understanding of its’ definition, risk factors, prevalance, deficits and natural history it’s hoped chiropractors may provide leadership in this area and fill this unmet clinical need.