Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a top cause of disability and yet treatment regimens aimed towards this disorder are highly varied and have limited and/or short-term efficacy.1 This is why LBP remains a high priority research avenue within the health sciences,2 where it is particularly needed in the manual therapies as the science is less complete.3

The spinal biomechanics literature has evolved to recognize the importance of the lumbar lordosis, particularly the loss of the distal lumbar lordosis as a cause for back pain.4,5 Recent advancements in manual therapy has shown that non-surgical lumbar extension traction (LET) methods are effective for increasing the lumbar lordosis in multimodal rehabilitation programs.6–8 In fact, a recent systematic review located 4 manuscripts6–9 documenting 3 clinical trials showing a 7–11° increase in lumbar lordosis over the course of 10–12 weeks after 30–36 treatment sessions.10 An additional randomized trial, using the lumbar Denneroll™ orthotic as the LET device, found that an increased lumbar lordosis was associated with improved back pain, disability, and lumbar lordosis in the group receiving LET applied 3 sessions per week over the course of 10-weeks, though the magnitude of the change was not reported.11

These LET trials have demonstrated the use of LET as a part of a multimodal rehabilitation program in patients with chronic mechanical LBP7–11 as well as discogenic lumbosacral radiculopathy.6 These 2 conditions (CLBP and lumbosacral radiculopathy) represent only 2 disorders of many possible low back conditions that patients may seek care for. Due to ever increasing efforts to increase provider treatment guidelines, lesser levels of scientific evidence, such as case reports, often become important in offering guidance in the treatment of different spinal conditions,12,13 including low back conditions lacking higher levels of documented evidence (i.e. randomized clinical trial).

The purpose of this review is to examine the clinical evidence of CBP technique methods of LET as used to increase lumbar lordosis in patients presenting with low back disorders having radiographically-diagnosed hypolordosis. We specifically aim to locate the scientific evidence as documented in case reports and series. Additionally, we offer suggestions for improvement of future clinical investigations and areas of needed research.

Methods

This review evaluated case reports/series reporting on LET rehabilitation of patients suffering from low back ailments having loss of lumbar spine lordosis and the clinical outcomes reported from CBP technique methods. Inclusion criteria required the report to use CBP LET methods to increase the lumbar lordosis. All ages and types of patient conditions were considered. Papers were obtained from the CBP NonProfit14 website citation listings, as they are updated yearly (every fall). Only peer-reviewed manuscripts were considered.

LET can be performed supine, seated, or standing. In each case, setups are similar and consider several features of the patient’s spine and posture alignment including: 1) sagittal translation to determine neutral or posterior or anterior positioning of the ribcage, 2) apex of the lumbar curve abnormality to determine location and angle of traction pull, 3) sacral inclination angle to determine thigh vs. pelvic constraint, 4) thoracic kyphosis to determine location of any thoracic constraint or support, and 5) pelvic to feet posture. For the purpose of this review, each method is considered an effective type of 3-point bending LET and are shown in Figure 1.

To ensure completeness, a further search was conducted in the Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL) and Pubmed databases for cases published within the last year (Oct. 2021-July 2022). Search terms included lumbar spine, lumbar lordosis, hypolordosis, combined with Chiropractic Biophysics, CBP, traction, rehabilitation, restoration and improvement. Any located reports were screened for related references. Authors with multiple case reports on CBP methods were also individually searched on ICL, Pubmed and ResearchGate to locate any qualifying cases involving the lumbar spine.

Papers listed on the CBP NonProfit website were systematically evaluated for documentation of treatments that aimed to correct lumbar hypolordosis deformities in the sagittal plane. The first 2 authors independently extracted details from included cases with any discrepancies decided among all three authors. All 129 papers listed on the CBP NonProfit website were screened for lumbar rehabilitation via CBP LET methods. Extracted details of the patients included: age, sex, primary complaint, treatment duration, treatment specifics (traction set-up), number of treatments, traction duration, exercise protocols and adjustment protocols. Extracted x-ray metrics included measured lordosis using absolute rotational angle (ARA), sacral base angle (SBA) thoracic translation in the sagittal plane (TzT) and any pelvic morphology measures. Further, pain and disability scores were noted, including the numerical pain rating scale (NPRS) and the Oswestry low back pain disability index (ODI).

Results

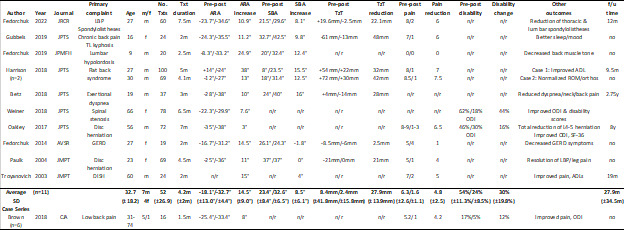

Our search located 17 patients reported in 11 separate publications as treated by CBP methods to increase lumbar hypolordosis (Table 1).15–25 All manuscripts except one were listed on the CBP NP website and only the Fedorchuk case15 was identified through the database search within the last year.

There were 2 case series (Brown, n=625; Harrison, n=218) and 9 single patient reports.15–17,19–24 The low back conditions documenting improvement associated with increasing lumbar lordosis included: chronic LBP,15,16,18–21,23–25 disc herniation,21,23 spinal stenosis,20 thoracolumbar kyphosis,16 flat back syndrome,18 diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH),24 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),22 and exertional dyspnea.19 One case reported a child aged 9,17 all others featured adults.

An average of the treatment results (not including the Brown25 series that reported a group average), showed an increase in lumbar lordosis of 15° after 51 treatments over 3.9 months to 10 patients (6m; 4f) of an average age of 33 years. There was also an average 8.6° increase in sacral base angle corresponding with an average reduction of anterior thoracic translation of 29mm (some reported reduction of posterior thoracic translation). The average pain intensity decreased 4.6 points on an 11-point pain rating scale. Two cases reported Oswestry low back pain disability scores (ODI) showing a decrease of 44%19 and 16%20 over 6.5 and 7 months, respectively.

The Brown case series (n=6) reported an average increase in lumbar lordosis of 8° after 16 treatments over 1.5 months.25 There was an average decrease of pain intensity of 4.2 points, and an average 12% decrease in ODI. There was no follow-up reported. Traction consisted of a seated lumbar extension traction.

Overall, there were 5 of 17 (29%) cases that reported a follow-up period (9.5m18; 12m15; 19m20; 2.75y-Case 119; 8y21); of these, all reported a maintenance of wellness (i.e. maintained initial symptom improvement). Upon follow-up, one case reported a continued improvement in lordosis,18 two cases showed a maintenance of lordosis,15,21 one case did not report follow up x-ray metrics,24 and one case showed a loss of lordosis19; however, in the latter case there was a maintenance of thoracic kyphosis and a further improved APD:TTD ratio (a metric for chest dimension ratio for the straight spine syndrome) in a patient treated for exertional dyspnea.

Discussion

In our selective review of papers reporting the rehabilitation of lumbar hypolordosis by CBP LET methods we located 17 patients as reported in 11 separate manuscripts. On average, there was an x-ray measured 15° improved lumbar lordosis, an 8.5° increased SBA, and a 28mm reduction in anterior thoracic translation posture after 52 treatments applied over the course of 4.2 months. These changes corresponded with a 4.8 point drop in the NPRS. These case studies reported the results from 12 males and 5 females ranging in age from 9 to 74 years.

Excluding the series by Brown,25 there was an average 14.5° change in lordosis over 52 treatments, which translates to a 0.28° change in lumbar lordosis per treatment. This is on par with what has been demonstrated in both non-randomized and randomized clinical trials on CBP LET methods.6–9 The various clinical trials showed a range of 0.21-0.31° improvement in lordosis per treatment.26 Although various case reports may have variation from this average change per treatment; it seems case reports are consistent with clinical trials and demonstrate that a 1° improvement in lumbar lordosis can be achieved after approximately 3-5 treatments. To note, the Brown series25 averaged 0.5° improvement per treatment in 6 patients. LET in the Brown case series,25 however, began in the initial week of beginning care, whereas in most of the other case reports, LET application began 1-3 weeks following traditional treatment applications (spinal manipulation, stretching, ice, etc…); thus, the results are similar considering LET actual dosages.

Assessing the average lumbar lordosis improvement over treatment number employing LET methods is an important evidence-based approach to extrapolate treatment duration needed for individual presenting LBP patients. This obviously applies to the incorporation of LET methods which is based on radiographic assessment screening of a patient’s presenting sagittal lumbar spine. This raises several questions for debate regarding the routine utilization of spine radiographs including understanding of and using contemporary lumbopelvic parameters, and the implications of not using X-ray.

First, contemporary understanding of the lumbopelvic sagittal spine alignment is essential and can only efficiently be screened for by using standing radiographs, and of course, repeat radiographs to assess treatment response. The analysis of the lumbar lordosis (LL) is now precisely understood where it cannot be simply assessed as a single angle of LL curvature in isolation. Rather the congruence/incongruence of how the LL is correlated to both the sacral inclination angle (SIA) and the patient’s angle of pelvic morphology (PM) is mandatory.27–33 Importantly, an individual’s correlation between LL vs. SIA and both SIA and LL vs. PM has been demonstrated to determine the presence or absence of LBP, disability, need for intervention, and outcomes.27–33 Further, the difference between LL and PM (i.e., LL minus PM) and sagittal balance (translation) are essential variables known to be associated with LBP.27–33

It is a criticism of all case reports located from this review as well as from all previous clinical trials on LET methods that none have reported on a patient’s predicted ideal lumbar curve after taking into account their unique pelvic morphology.10 It has been illustrated elsewhere10 how future studies on use of LET methods requires the consideration of pelvic morphology and the relationships of SIA and LL as expressed above. As mentioned, different relationships or ‘fits’ of the lumbar lordosis relative to both the SBA and pelvic incidence angle can explain normal distributions as well as abnormal relationships of the lumbar lordosis in normal vs. chronic low back pain populations.27–33 This current advanced understanding needs to be considered in future presentations regarding treatment of patients by LET methods.

Second, as pointed out in the literature recently, the implications of not taking screening radiographs of a patient’s presenting lumbopelvic spinal parameters are significant. Treatment would not take alignment into consideration and therefore be akin to ‘black box’ or blinded treatment. Although the patient may experience temporary pain relief from many physiotherapeutic modalities, these have been shown to fail in the long-term if the lordotic curve of the low back is not rehabilitated.6–8,10

Finally, routine X-ray screening of LBP patients would allow biomechanical diagnoses to be made and treatments could be custom tailored to meet the patient’s biomechanical needs in the relief of their ailment. This type of practice requires routine imaging which defies some anti-imaging advocates,34–36 but could lead to evidence-based, ethical and patient-specific treatments to achieve more successful long-term outcomes.

The limitations to this review include the limited number of citations located and the limited number of lumbar disorders of the presenting patients. It was also noted that the quality of the case reports located varied and details regarding treatment and outcomes were sometimes missing. There were only four cases that included long term follow-up. Future cases utilizing CBP LET methods need to include metrics on pelvic morphology, relationships between LL and SIA, include body mass index information,32 include a follow-up period of at least 6-12 months, and include standardized pain, disability and quality of life data for each case.

CONCLUSION

There is an evolving evidence base involving case reporting on the successful management of CBP LET procedures in the rehabilitation of the lumbar lordosis. The available case reports are in general agreement with clinical trial results and approximate treatment durations can be estimated from the existing data. Current understanding of lumbopelvic alignment supports the routine radiographic screening of patients presenting with low back disorders to make a definitive biomechanical diagnosis and to determine patient-specific treatment needs.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Paul Oakley (PAO) is a paid consultant for CBP NonProfit, Inc.; Dr. Deed Harrison (DEH) teaches chiropractic rehabilitation methods and sells products to physicians for patient care as used in this manuscript.

_methods._let_can_be_performed_supine_(upper_left_in_office.jpeg)

_methods._let_can_be_performed_supine_(upper_left_in_office.jpeg)