Introduction

Over the past 10-years, the guidelines for the evaluation and management of nonspecific chronic low back pain have evolved significantly. In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain were updated so that the #1 recommendation was to utilize spinal manipulation, exercise, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation prior to pharmaceutical intervention as a first line of defense. It was advised to only consider the use of opioids after failed trials of different conservative care methods failed to find benefit from non-opioid therapy such as Tramadol or Duloxetine; also that the benefit to be gained would outweigh the significant potential for negative effects.1

The previous 2007 ACP and the American Pain Society Joint Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain did not mention conservative care intervention until Recommendation #7 (of 7), which it rates as a “weak recommendation” supported by “moderate-quality evidence.”2 Recommendation #6 additionally speaks to suggesting that the first line of defense for chronic low back pain should be non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. The recommendation goes on to include that physicians doubtful that non-steroidal anti-inflammatories would be beneficial to the patient, that a prescription of an opioid analgesic is the next viable option for managing chronic low back pain. The guidelines rate this as a “strong recommendation” supported by “moderate-quality evidence.”2

It remains unclear what the outcome measures are, both in terms of functional quality of life and pain disability, for patients who have chronic low back pain managed with long-term opioid use. This is largely due to the fact that the randomized controlled trials seeking to evaluate this do not persist longer than 4-months duration, leaving the only long-term evaluation to a handful of observational studies.3 Even with little indication to suggest that long-term management by opioids would be beneficial to this chronic pain population, by 2012, nearly 25% of all VA outpatient veterans receiving care were receiving an opioid prescription.4

The updated management guidelines in 2017 unfortunately did not undo the decades of patients that were having their chronic pain managed by daily opioid use; however, it did set new restrictions and best practice guidelines for physicians that pushed them to wean patients off. It also created a new chronic pain patient population with unique complications: physical dependence, tolerance, and hyperalgesia associated with the chronic opioid use.5–7 Both physicians and patients sought alternative avenues of pain management after years, sometimes over a decade, of prior management by some of the most powerful pharmaceuticals available.

There is little-to-no research to speak to the indication or prognosis of attempting a trial of conservative care after the patient has already had long-term management with daily opioid use. Two individual case studies were published in 2018 that demonstrate a significant improvement in outcome measures of patients with chronic low back pain previously managed by daily high-dose opioid use.8,9 One study’s intervention is specific to chiropractic spinal manipulation8; the other, a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program in Germany.9

The purpose of this case report is to demonstrate the ability for a patient with chronic mid and low back pain to make significant improvements, both in pain score and quality of life, with a trial of chiropractic care, even after a decade of management with daily opioid use.

Case Report

A 50-year-old male veteran presented with chronic mid and low back pain with associated radiating symptoms into bilateral lower extremities that was medically managed for 10-years with opioids in the form of hydrocodone and morphine. It was well documented that he had presented to his Veterans Affairs primary care provider a multitude of times complaining of unremitting mid and low back pain. Their appointment notes reported that he had stopped performing weight exercises, biking, and any initiative to be active due to his pain. He was issued a cane and crutches for flare-ups on separate occasions. He reported “fatigue and lack of desire to do things”. The only medical intervention offered, over a 10-year period, for his chronic pain was opioids. In June 2018, the patient notified his primary care provider that he had independently discontinued all opioid use.

He presented to the Veterans Affairs Medical Center chiropractic clinic in August 2018, 2-months after discontinuing opioids. He was attempting to manage his pain with 1000mg of over-the-counter pain medication a day. He reported a constant 7/10 Verbal Numeric Rating Scale (VNRS) score. He located his pain on the left side of the mid thoracic region where he had trauma without resulting pathology many years ago. He additionally presented with 5/10 VNRS low back pain with radiating pain into bilateral lower extremities, traveling distally into the feet. He reported having exacerbations of pain with “every movement.” He described the pain as an achiness that could be sharp/shooting at times. He stated that he was not active, not exercising on a regular basis, and had just cancelled his gym membership.

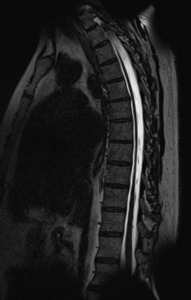

MRI of the thoracic spine revealed a trace T5-T6 disc bulge with trace effacement of the anterior thecal sac, without significant central canal narrowing (Figure 1). MRI of the lumbar spine revealed a L4-L5 left paracentral disc protrusion that extended to the left neural foramen (Figure 2).

The initial evaluation performed by the chiropractic clinic revealed full ranges of motion with flexion provoking radiating pain into the right buttock, left rotation provoking mid back pain, and extension provoking mid back pain and left sided low back pain. Orthopedic testing was largely unremarkable aside from a positive Kemp’s Test, assessing lumbar facet joints, which was provocative to localized lumbar pain bilaterally. Neural tension signs were negative bilaterally. Sacroiliac Compression Test revealed provocation to pain in the left sacroiliac joint. Upon palpation, restricted motion was also noted in the lumbar and thoracic regions. The patient presented neurologically intact with 5/5 myotome strength in the lower extremities, sensation that was bilateral and symmetrical, +2 deep tendon reflexes at L4 and S1, and no pathological reflexes identified.

During the initial visit, he was treated with high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) manual spinal manipulation to the thoracic, lumbar, and pelvic regions. On his second follow-up visit, he reported no significant improvement after his first treatment. He also reported that he provoked his low back pain and now had constant pain radiating into the bilateral lower extremities increased with lumbar flexion.

Over a 3-month period, the patient received 5 visits of chiropractic care consisting of manual spinal manipulation, in addition to in-office thermotherapy, and flexion-distraction therapy. He was issued a foam roller and an at-home stretching regimen to mobilize his spine and pelvis. At each visit, the patient was encouraged to find ways to increase his activity level. By the fourth visit, the patient had 4/10 VNRS mid and low back pain and reported his peripheral symptoms decreased in frequency and intensity. The patient had become much more physically active, exercising with his wife and remodeling their home. Lumbar ranges of motion were within normal limits, non-provocative to the low back pain, and did not produce any radiating symptoms. At this point in time, an at-home lumbar traction unit was ordered.

The patient presented for a re-evaluation on the 6th visit. He had just returned from a trip a week prior that had created some myofascial pain in his mid-back but did not affect his low back. He presented to the clinic with 5/10 VNRS mid back pain and 2/10 VNRS low back pain without any radiation into the lower extremities. Upon evaluation, he had full and non-provocative ranges of motion. The patient stated that the last 3-months of chiropractic care provided him with roughly a 50% reduction in pain; more importantly, he reported a significant increase in his functionality and quality of life. The patient reported he felt competent and comfortable managing his pain with the provided self-management techniques.

The patient’s primary treatment goal was to manage his pain independently with minimal pharmaceutical intervention, which he felt was achieved. The patient was able to remain independent from opioids and even decreased his daily over-the-counter pain medication from 1000mg a day to 600mg. He had begun remodeling his home and was looking forward to working on it with his son. He was exercising regularly and walking with his wife. The patient understood that abolishing his pain was unrealistic but reported that it had a significantly reduced effect on his daily life.

The patient returned for as-needed treatment 8-months later. He had continued his self-management strategies with good relief. He presented with 5/10 mid and low back pain with intermittent peripheral symptoms that he attributed to continuing to remodel his house. He had full ranges of motion, with extension being the only provocative range. An additional 5 visits extended over 3-months were able to control his pain to a 3/10 and abolish peripheral symptoms. He was again discharged to as needed.

Discussion

The 2017 updated VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain created new opportunities for Veterans Affairs conservative care providers like chiropractors.10 As opioid use to manage chronic pain patients became discouraged, physicians and patients alike began searching for alternatives. Since the update in 2017, the amount of publications regarding chiropractic treatment of veterans and opioid use has significantly expanded.11–15

This case report portrays the ability for a patient with chronic thoracic and low back pain for over a decade, who was previously medically managed for 10 years with daily opioids, to achieve significant improvements with autonomous management of pain, increased functionality, and improved quality of life with a trial of 6 visits of chiropractic care. There is still more research needed to determine what potential functional and disability gains could be made from trialing chiropractic care after long-term opioid management for chronic pain.

Limitations

These results are representative of a single case and may not be applicable to every patient with chronic back pain. Recording truly objective outcome measures when assessing and managing chronic pain can be difficult; however, assessment was able to be performed with a number of different methods such as: review of historical documentation in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) through additional medical providers for the patient, subjective reporting from the patient, and observations from the practitioners.

Conclusion

The clinical progress of this case suggests that for some patients with non-cancer back pain, a trial of chiropractic care, even after a decade of daily management with opioids, can still be significantly beneficial to quality of life.