Introduction

Syringomyelia (syrinx) is characterized by a fluid-filled cavity within the central canal of the spinal cord.1 Although it can occur anywhere between the brainstem and the conus medullaris, the most common location for a syrinx to develop is in the cervical and thoracic regions, between C2 and T9.2 Depending on the size of the lesion, it can put pressure on the tracts within the spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and atrophy, lower limb spasticity and ataxia, and a cape-like loss of pain and temperature sensation with preserved sense of touch and vibration.1

The following case report is a chronological case with findings on advanced imaging taken over a period of 6 years. It discusses the imaging findings of a spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia. Full or partial spontaneous resolution may occur; however, it is considered an uncommon event. It has only been documented in the literature 39 times, and only 33% of those cases undergo complete regression.3 Additionally, 5% of documented cases experienced a recurrence following spontaneous resolution.3 Complete spontaneous resolution is an uncommon occurrence and is not traceable to a specific intervention or therapy.

Case Report

Clinical History

A 33-year-old male patient experienced a traumatic accident while grooming snowmobile trails in 2013. He hit his head and lost consciousness after being ejected from the vehicle. He experienced pain at the base of the skull, severe nonspecific headaches, pain behind the eyes, neck pain, and dizziness. The symptoms were exacerbated upon quick movement and improved upon rest. He denied any numbness, tingling, pain, or loss of motor function down the arms. He visited an emergency room and received a CT of his head and cervical spine. The imaging was reported normal, and he was released.

Examination

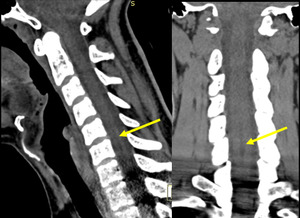

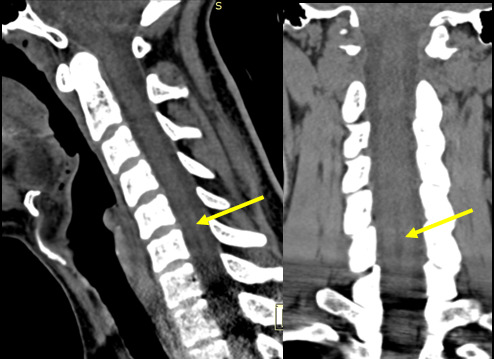

The initial CT (Figure 1) was taken in 2013. He then received intermittent physical therapy and chiropractic care from various providers from 2013-2019 for his headaches and neck pain, with little improvement seen. Due to lack of improvement, in 2016, an MRI of the cervical spine was performed (Figure 2) which revealed a fluid-filled dilatation in the central canal consistent with syringomyelia at C5-C7 measuring 26mm x 4mm x 5mm. Retrospective review of the CT study shows a subtle hypoattenuation in the central cord at C5-C7 indicating the syrinx was present at the time of the accident. In 2019, a subsequent MRI (Figure 3) demonstrated no significant change in the size or shape of the syringomyelia. In 2021, the patient gradually noticed an improvement in the frequency and duration of his headaches and dizziness. A final MRI was performed (Figure 4) which revealed a complete resolution of the syringomyelia. The patient continues intermittent chiropractic care for other unrelated complaints.

Outcomes

The patient had a complete spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of syringomyelia is disruption or obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid flow.2 This causes a change in the pressure within the spinal canal, which can cause an accumulation of fluid in or around the central canal, resulting in a syrinx.4 Common etiologies of syringomyelia include congenital anomalies such as Chiari Malformation, Klippel-Feil syndrome, spinal stenosis, tethered cord syndrome, or split-cord malformation. Other etiologies include spinal cord tumor, infection, inflammation, trauma, or idiopathic.2

In our case, the patient did not have any congenital anomalies, tumor, or infection. Another consideration is that post-traumatic syringomyelia occurs 1 month to 45 years after injury5 and, in our patient, the syrinx was visualized on the initial CT study immediately following the traumatic accident. Therefore, our patient’s syringomyelia was likely idiopathic in nature.

Syringomyelia is a concern because it is usually accompanied by peripheral neurologic deficits. However, continuous hydrostatic stress can also damage the spinal cord regardless of peripheral symptoms.6 Uneven tissue expansion can cause damage to dendrites, axons, synapses, and glial cells, which can present as demyelination, shearing, and tearing of the cell membranes. Additionally, there can be disruption of the blood-spinal cord barrier that can cause further edema.6

Surgery is the current accepted intervention for syringomyelia. The 2 most common surgical approaches are to restore cerebrospinal fluid flow by draining the syrinx or by removing or altering the obstruction.2 According to a study published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, surgical intervention is successful at decreasing both the diameter and length of the syrinx on magnetic resonance imaging in all cases.7 Clinically, 94% of patients have had improved symptoms after surgical decompression but residual symptoms including pain or loss of sensation persist in 68% of patients.7 This is due to the fact the surgery can reverse the pathophysiological process that leads to the development of the syrinx, but it cannot reverse any permanent destruction to the spinal cord.7

While surgical intervention is effective at decreasing the syrinx, there are associated risks such as bleeding, infection, negative response to anesthesia, scar tissue formation, residual symptoms, or permanent spinal cord damage.2 In addition, full or partial spontaneous resolution may occur though is uncommon. Therefore, there is debate on whether intervention is necessary for mild cases of syringomyelia.2

While surgery is the most common intervention for reduction of syringomyelia, it is not the only solution. Conservative management is the recommended treatment for syringomyelia in absence of surgical indicators such as disrupted flow of cerebrospinal fluid, enlargement of the syrinx over time, and progressive neurologic deficits.8 Appropriate therapies include spinal mobilization, therapeutic ultrasound, instrument-assisted soft-tissue mobilization, and physical therapy.9 High-velocity low-amplitude adjusting can also be beneficial except in cases of post-traumatic syringomyelia. In these cases, stretching and traction can provide relief without the risk of rupturing the syrinx and damage to the spinal cord.8 Although conservative care has not been shown to reduce syringomyelia, it can improve symptoms associated with a syrinx, giving patients a better quality of life without surgery.

Limitations

It is important to note that this is a case report of only a single patient.

Since the cause of the complete spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia is unknown and the study is limited, the findings of this report cannot be generalized to other cases.

Conclusion

The objective of this case report was to describe coincidental imaging findings of a complete spontaneous resolution of idiopathic syringomyelia. Spontaneous resolution of syringomyelia is considered uncommon, with only one-third of documented cases in the literature describing complete regression.